International Renown

As one would expect of a woman who waited decades for promotions that adequately reflected her level of scholarship and role as student instructor, Croasdale was disproportionately underpaid for her work, even when compared to her female colleagues at other institutions. However, she was able to support herself and her ailing mother with royalty checks from C.L. Wilson’s Botany, a book for which she contributed the botanical illustrations. These royalty checks also gave Croasdale the freedom to travel abroad—for business, of course.

In 1951, she traveled to Scandinavia to finally meet some contemporaries doing avant-garde research she found fascinating. During her first trip to Europe, Croasdale met with Einar Tieling in Sweden and Rolf Grönblad in Finland. Communicating for the next few years only via letter, she collaborated with her new friends and even helped Tieling with drawings for his work on desmids, her area of expertise. This was Croasdale’s first big leap towards her international reputation and an important opportunity for her to find respect and peers outside of the sometimes suffocating Dartmouth community.

When Grönblad passed away suddenly, Croasdale was already helping him with research for an upcoming paper, which she went on to finish on her own. After the completion of their joint article, she was then contacted by the University of Finland to complete his other unfinished work. Immediately after the completion of that work, she was asked to do the same for yet another collgeaue; she later reflected that “[the incomplete work] came piling in, kind of half-done, some drawings, some notes.” Her competency and reliability—known across continents, across languages—made her the obvious choice.

In 1967, Croasdale was made President of the Phycological Society of America after serving as the Society’s Vice President in 1964. She noted in a letter to James Horning that the experience had been “interesting” but that she was drained by the constant demands on her time, especially for travel. She was expected to go to conferences on behalf of the Society and there was some issue getting the Department to cover her travel costs—which was their policy for faculty. Even a promotion or a success was often just another opportunity for her time to be consumed fighting for what she had already earned.

Croasdale continued to be contacted by scientists all over the world through to her old age, including frequent pen pals in India and Poland, and those who needed assistance with scientific Latin, a dying skill that Hannah had taught herself over the years. According to Croasdale, formal education in Latin had been intended only for male students in her school, so she did her best to learn on her own.

From the Archives

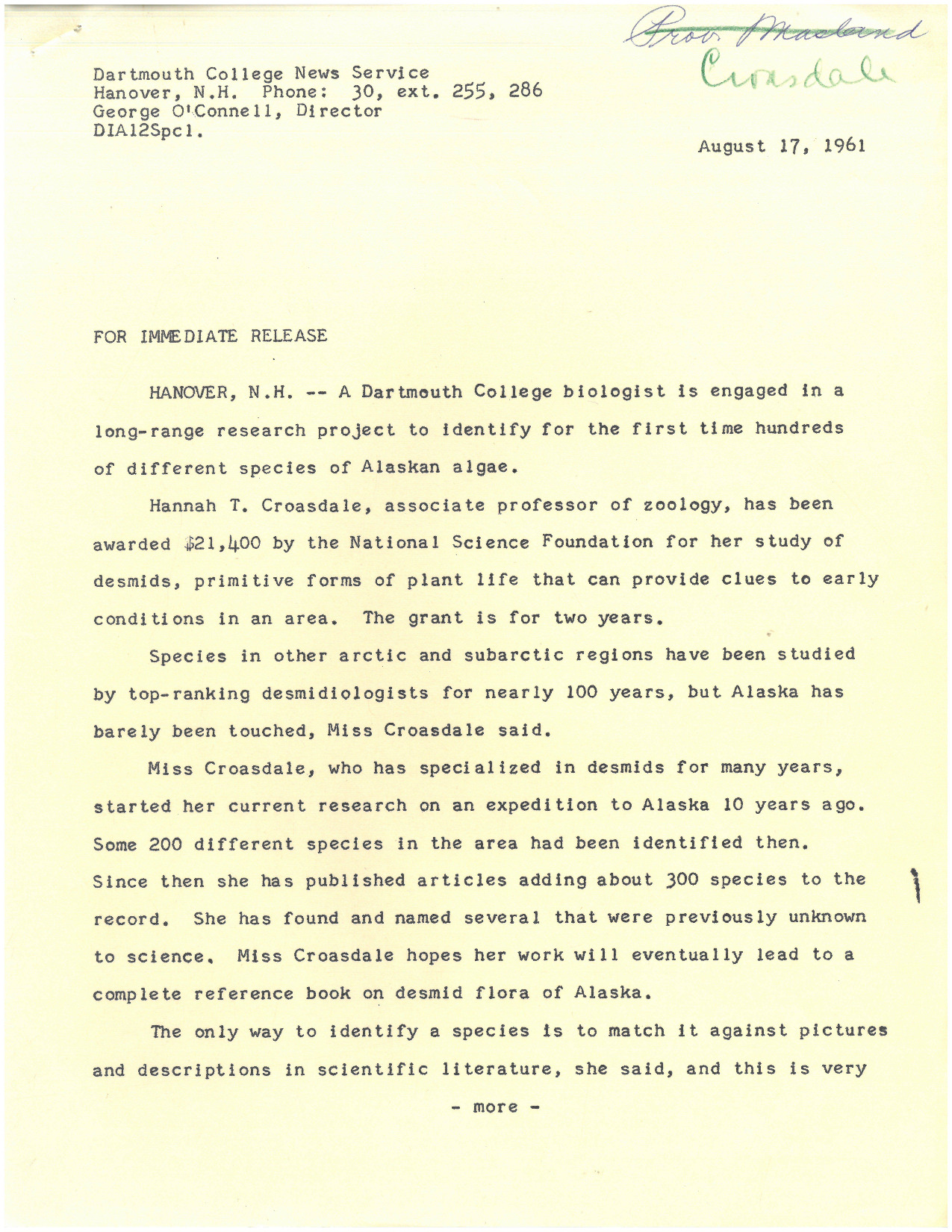

Press release announcing that Croasdale had received a National Science Foundation grant to identify hundreds of species of Alaskan algae for the first time. At the time untenured, Croasdale was promised leave without pay by Rieser if she was able to procure this grant. Croasdale would later remark that “everything has gone pretty well since [getting the grant].”

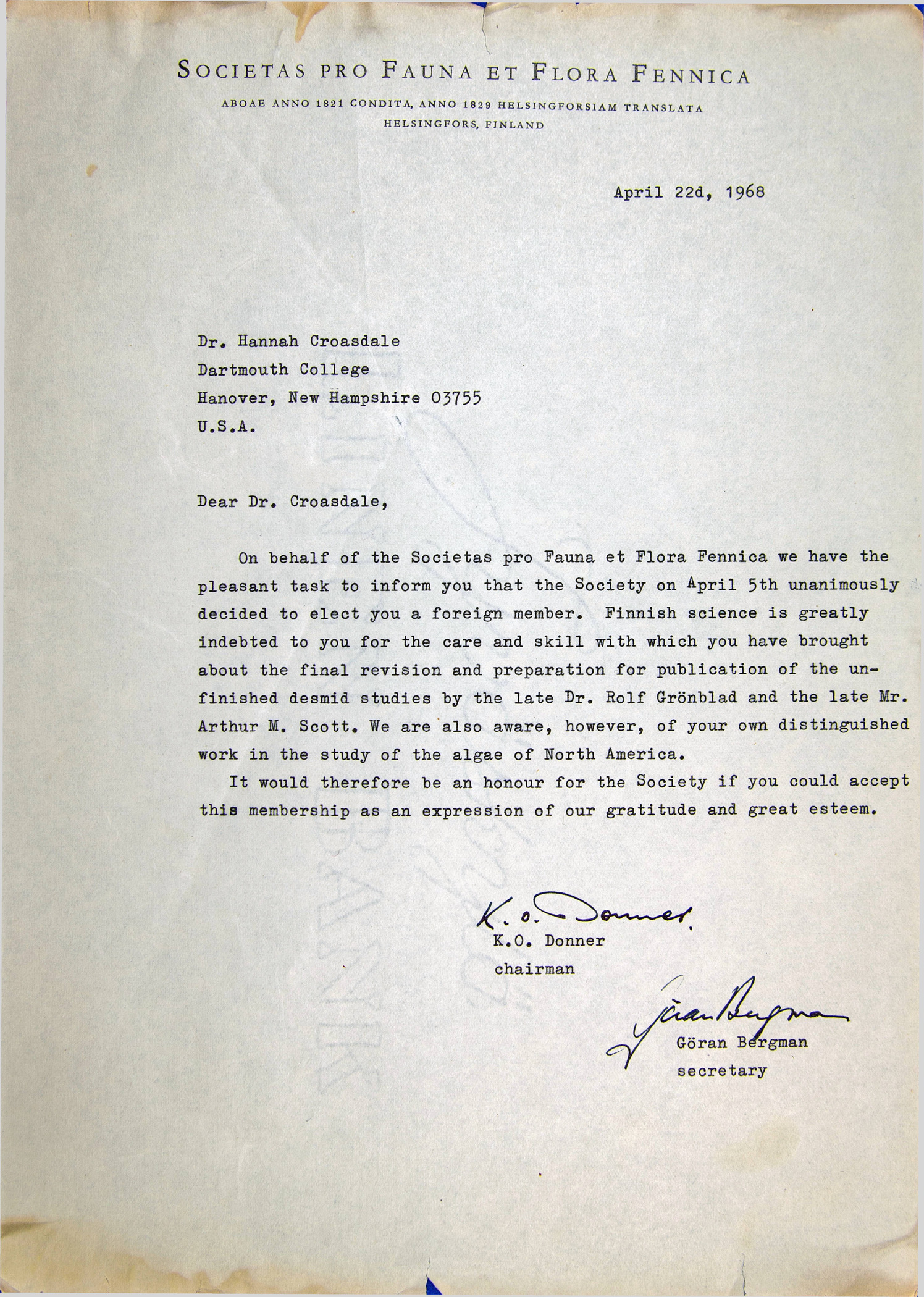

A letter from K.O. Donner and Göran Bergman of the Societas pro Fauna et Flora Fennica informing Prof. Croasdale that she has been unanimously elected a foreign member of the organization as of April 5, 1968.

Michael Wynne writes to Prof. Croasdale thanking her for her assistance with naming a specimen using scientific Latin, a language that Croasdale had taught herself. This letter serves as an excellent example that Croasdale was well-known domestically in the field of phycology and naming in scientific Latin.

Historical Accountability Student Research Program

Historical Accountability Student Research Program