The AIDS Quilt at Dartmouth

Within the ‘Dartmouth bubble,’ it may have been hard for students to understand the magnitude of the AIDS epidemic. The College was certainly far from the early epicenters of disease, and, according to Health Service records, no student tested positive for HIV during their time at Dartmouth. To shed light on the far-reaching impact of the epidemic, Dick’s House organized a campus-wide AIDS awareness week in May 1991. The program included talks from gay activists, a panel of people living with AIDS in the upper valley, and a documentary about the disease. Stacy Weeks ’91, president of the pre-medical society, described the purpose of the week, saying:

“One of the most important points about the whole AIDS awareness week in general is it’s going to change the notion that AIDS is something that gay people get who live in San Francisco … it’s going to make Dartmouth students aware of the fact that AIDS affects everyone.”

Stacy Weeks '91

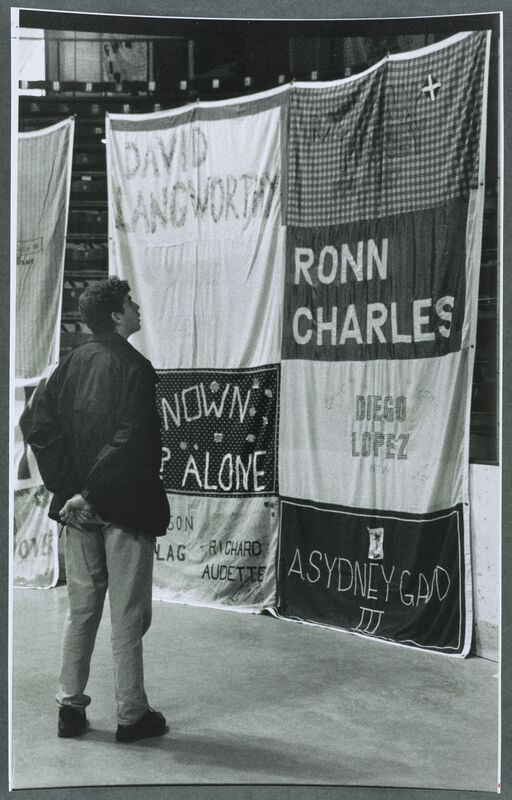

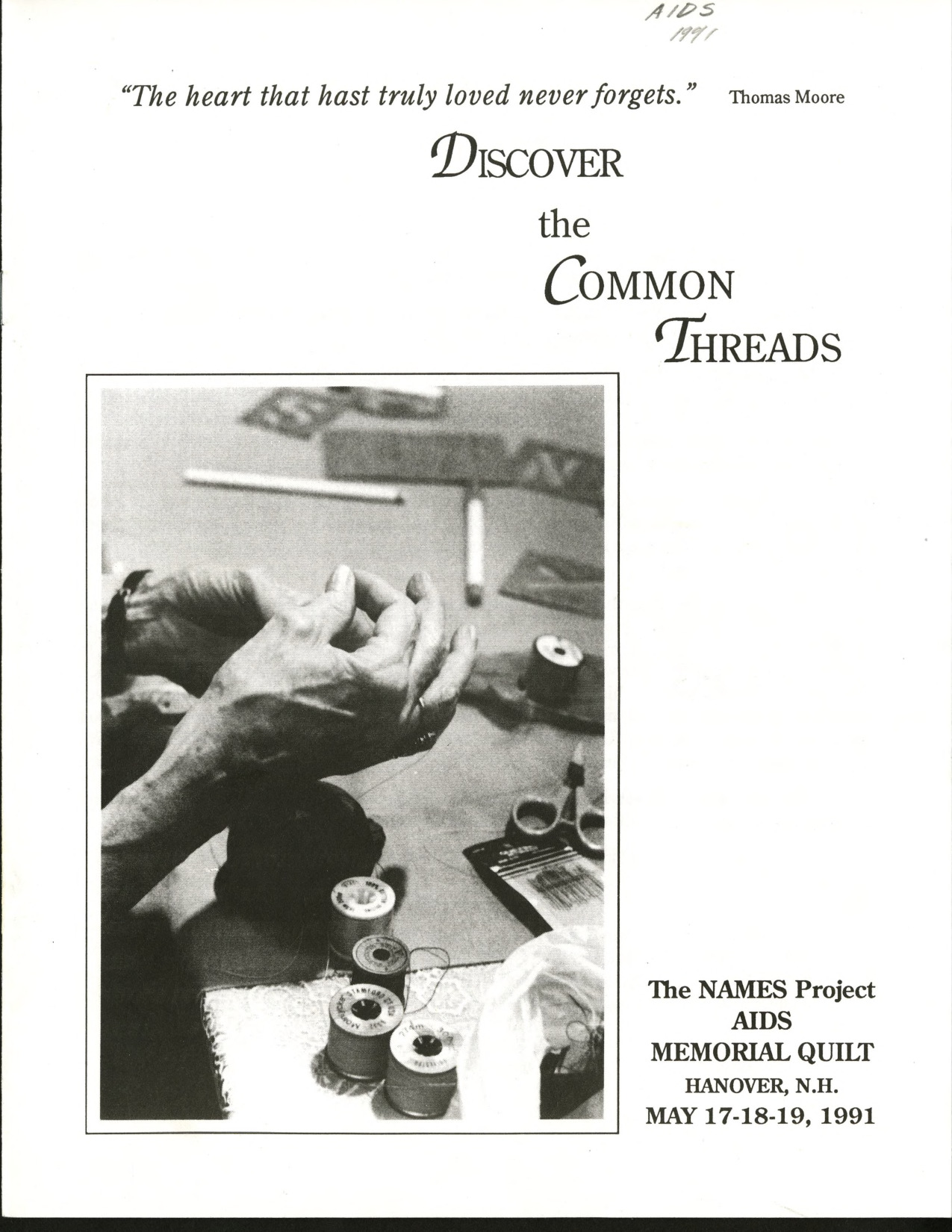

The centerpiece of the program was the visit of the NAMES Project AIDS memorial quilt. The quilt was originally created by Cleve Jones in 1985 in San Francisco as a memorial to loved ones lost to the disease.11 By 1991 it had grown to over 10,000 panels in size, featuring panels from all 50 states and 28 countries. In collaboration with the upper valley organization ACoRN (AIDS Community Resource Network), Dartmouth hosted a portion of the quilt in Thompson arena. The visit marked the first large-scale exhibition of the quilt in northern New England.

Community members and Dartmouth students alike were struck by the quilt. In an interview with the Valley News, one man discussed his deceased brother, who was commemorated in a quilt panel: “A hell of a guy. I miss him a lot.” Another Dartmouth student remarked in an interview with The Chronicle of Higher Education that “there’s no way [one] can’t identify with some aspect of this and really have it hit home.”

The quilt’s reception exemplified the progress and acceptance that the Dartmouth community had made regarding AIDS. From opening up to more progressive views about homosexuality to adopting safer sex practices, students had made far strides from the regressive environment of the early 1980s. As one RAID member put it: “You think [the quilt] would be just for gays, but then you see people who have died of AIDS as real people, not just stereotypes.”

In reflecting on how to end this exhibit, I was particularly moved by this story. The quilt was – and remains to this day – more than a memorial. Rather, it makes the unimaginable loss of a generation tangible. The memories of those lost to AIDS all over the country, and even the world, are commemorated in the panels created by their loved ones. To bring such an object to Dartmouth was to bring the world to Hanover – to burst the proverbial bubble and to connect our small College with the greater legacy of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

_______________________

11 National AIDS Memorial. “The History of the Quilt.” https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt-history.

From the Archives

Click on an image to access the full document, audio-visual components, and/or metadata associated with that item.

Historical Accountability Student Research Program

Historical Accountability Student Research Program