From Cents to Scholarships: Early Communities

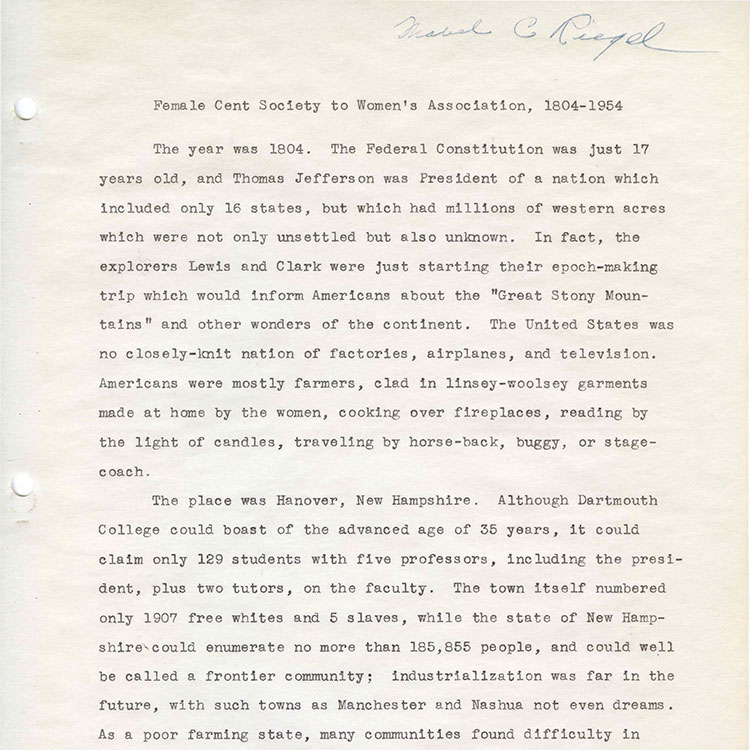

In 1954, Mabel C. Riegel wrote a detailed history of the women’s organizations at Dartmouth that culminated into the organization of which she was a member, the Women's Association of the Church of Christ at Dartmouth College. Riegel’s husband, Robert Riegel, was a history professor at Dartmouth who wrote several books on the history of feminism. In the preface to his book, American Feminists, he wrote, “I am as usual grateful to my wife Mabel C. Riegel, who has participated actively both in gathering and in interpreting the material.” Like Riegel, many women worked hard as their husbands’ office assistants, research partners, and more. This invisible labor is often not recorded, and Robert’s evident respect for his wife’s intellect may have helped her build the confidence to author (although not publish) her own work, which has been preserved in the Dartmouth archives.

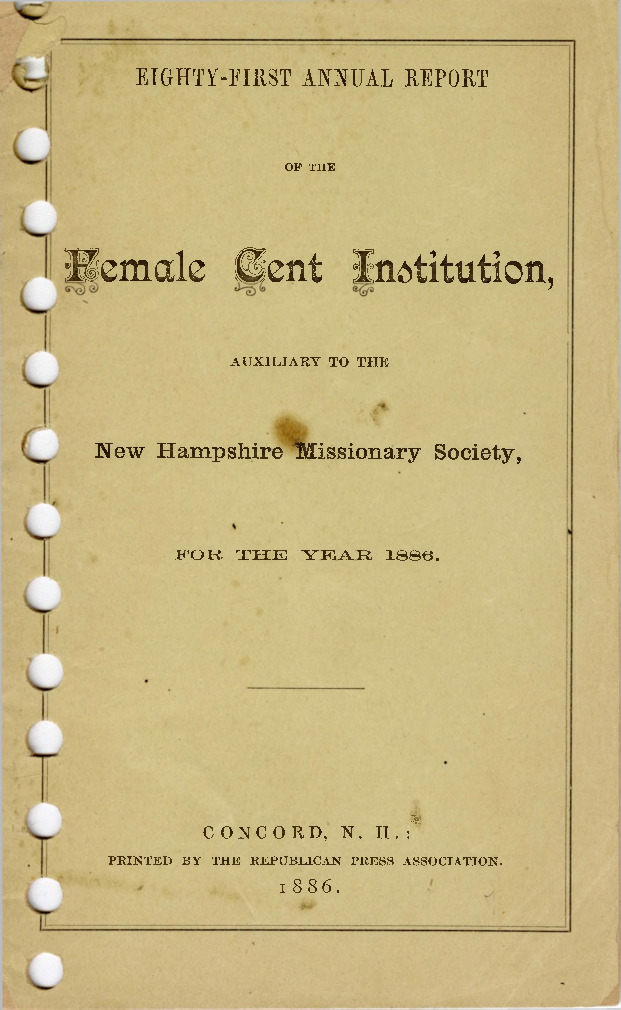

From Riegel’s research, it becomes clear that the success and longevity of women’s organizations relied upon their function as sources of charitable fundraising. In 1804, Elizabeth Kneeland McFarland, wife of reverend Dr. Asa McFarland, Class of 1793, and Dartmouth tutor, founded the Female Cent Society. McFarland rallied the women of Hanover to donate a cent each week to maintain their local church and donate to the Home Missionary Society. In 1806, the Society raised 14 per cent of the entire state’s contributions. Their contributions over next 14 years average to $30, about $600 in 2021.

Despite its success at fundraising, the Female Cent Society, with one officer and no regular meetings, was still a far cry from any socially meaningful female community. By 1871, local women began to crave community as more and more women moved to Hanover. Under the leadership of Mary Ann Sanborn, wife of Professor Edwin D. Sanborn, Chair of Latin and English Literature at Dartmouth, many women left the Female Cent Society to form to the Women’s Missionary Society. This new group continued the Female Cent Society’s legacy of philanthropy in 1891, when they founded the first scholarship in the history of Dartmouth-affiliated women’s clubs, although it is unclear who or what was entitled to receive the financial support.

There continued to be agitation for a room of their own, which in time resulted in the Vestry.

The Women’s Missionary Society also invited speakers to meetings and emphasized discussion of current events impacting international missions, which resulted in lively conversations that attracted the attention of their husbands: “Several deserted husbands [professors Chase, Hitchcock, and Bartlett] apparently decided that the ladies’ tea was better than preparing their own suppers.” The club meetings reversed traditional gender roles by allowing women to be the leaders of intellectual discourse and provided a space for women to escape their standard domestic duties when the Society moved out of the house and into the vestry of Christ Church in 1878. As Riegel notes, these women came to an important realization about 50 years ahead of Virginia Woolf: “There continued to be agitation for a room of their own, which in time resulted in the Vestry” (emphasis mine).

Like the Female Cent Society before it, which by necessity limited membership to women with disposable income for donations, the Women’s Missionary Society remained exclusive to white, upper-class women. Their missionary speakers, such as a Mrs. Gulick, discussed the “necessity of women’s work for heathen women,” or non-Christian, likely non-white women. Through missionary work, the women appeared to be aligning themselves with white, male power at the expense of women of color abroad at a time when United States imperialism was on the rise.

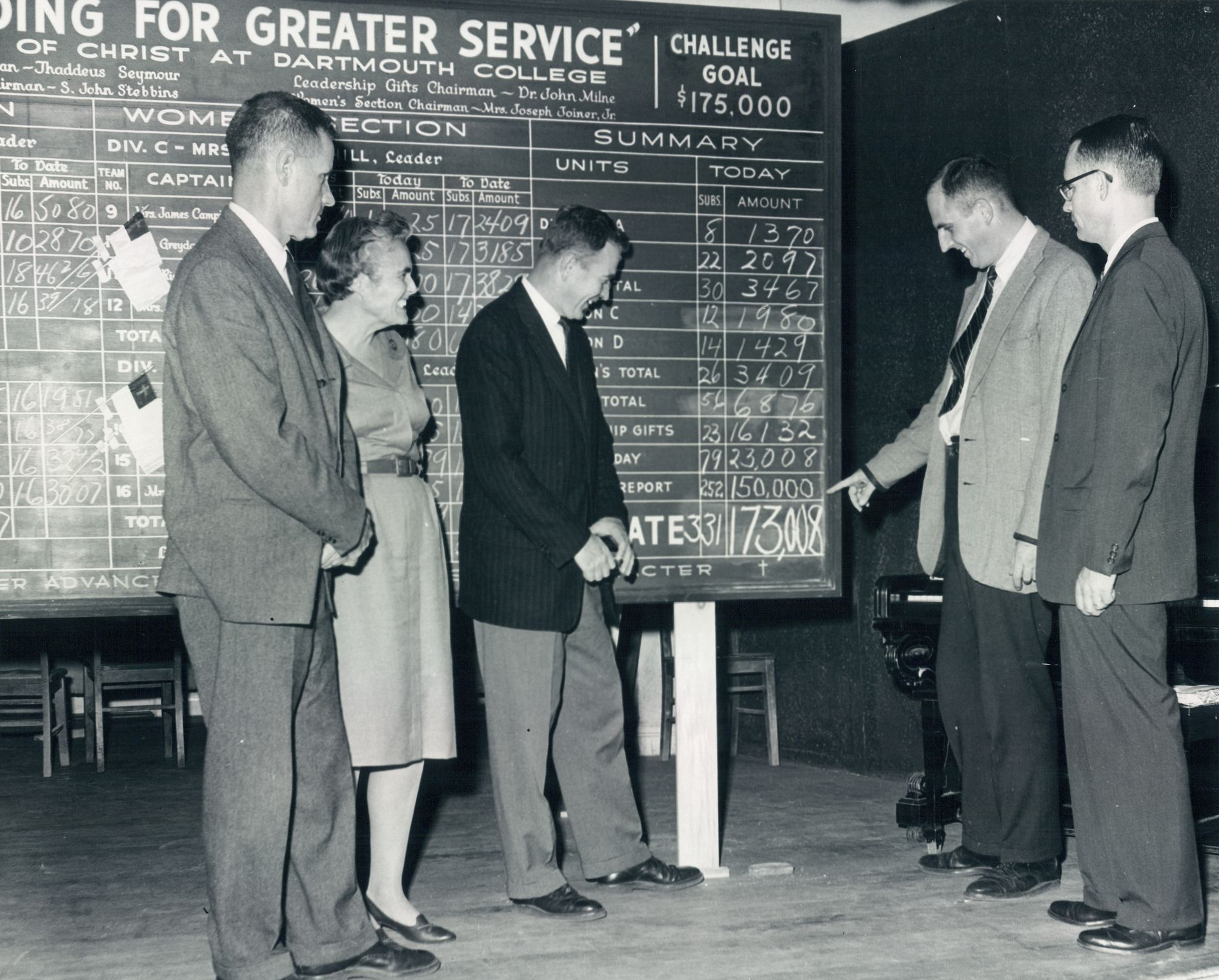

However, the group’s interest in international missions eventually waned, and the Society morphed into its final iteration as the Women’s Association of the Church of Christ at Dartmouth College. The group became more involved on Dartmouth’s campus as the church, as the name change indicates. Identified explicitly as Dartmouth women, they planned and prepared food for important charity and holiday events on campus, like Winter Carnival.

From cents to scholarships, these organized groups of women served as important early venues for more elite Dartmouth women to convene. Together, these three early groups set the precedent for many other groups filled with wives of Dartmouth graduates, faculty, and staff to form their own communities and legitimize themselves in the eyes of the college by creating scholarships and participating in charity events.

From the Archives

Click on an image to access the full document, audio-visual components, and/or metadata associated with that item.

A written history by Mabel C. Riegel documenting how the Female Cent Society in Hanover, NH became the Women's Association of the Church of Christ at Dartmouth College.

The eighty-first annual report of the Female Cent Institution, including opening remarks, funds collected, and lists of new members. In 1886, the combined funds collected from Hanover and Hanover Center total $27.20, which would be around $800.00 in 2021.

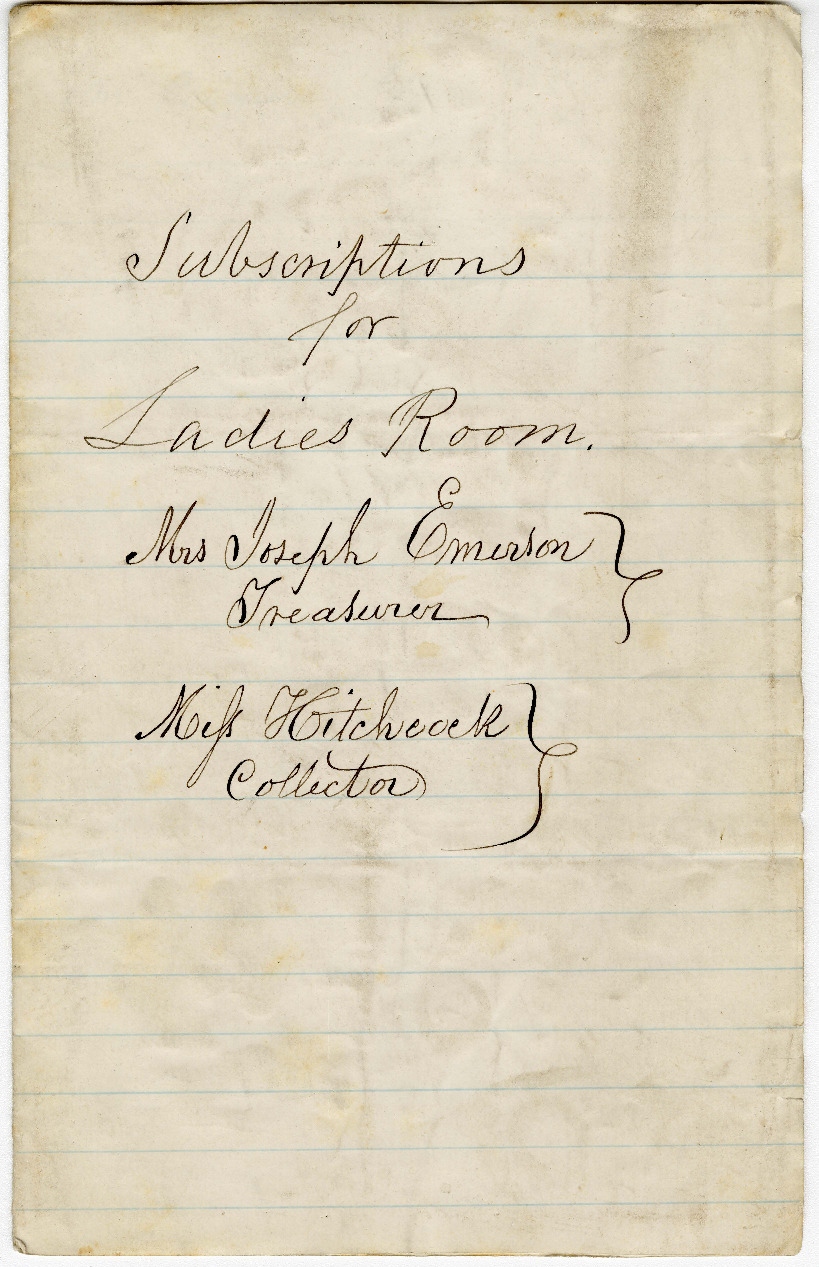

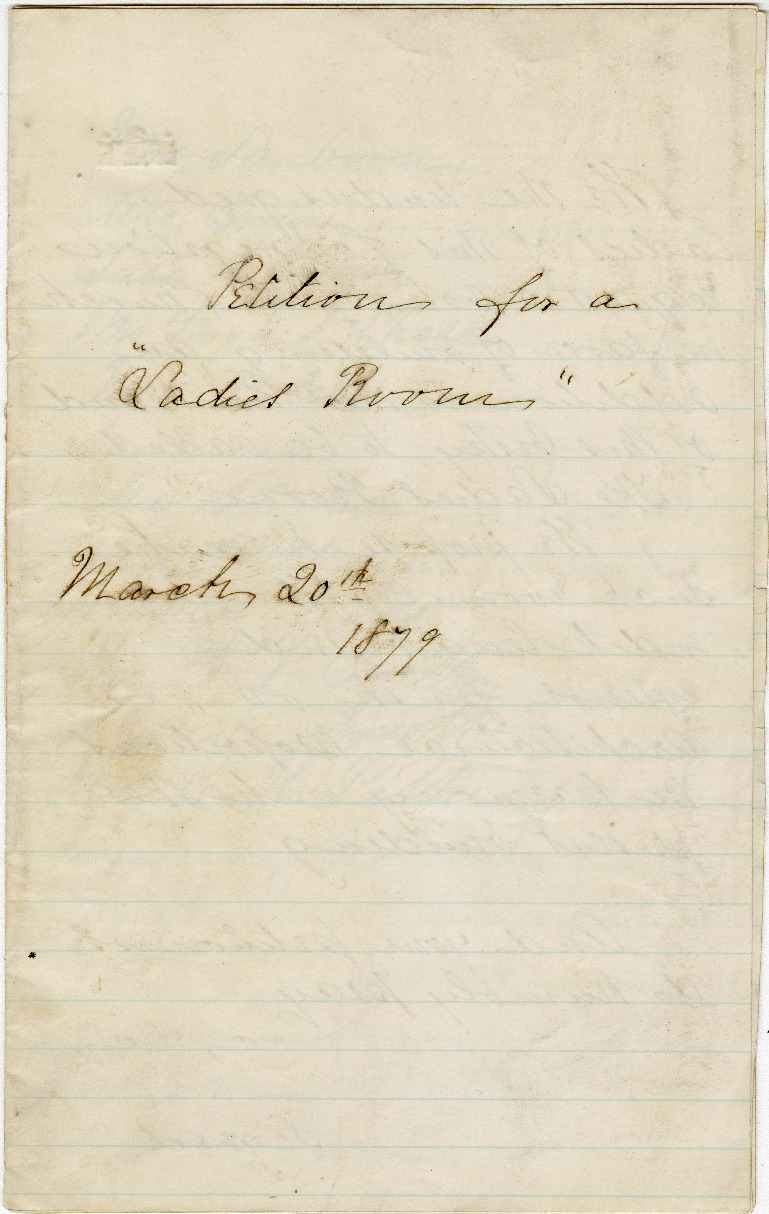

The original petition by women at the Church of Christ for a “Ladies Room” in which to hold Women's Association meetings and events.

Historical Accountability Student Research Program

Historical Accountability Student Research Program