-

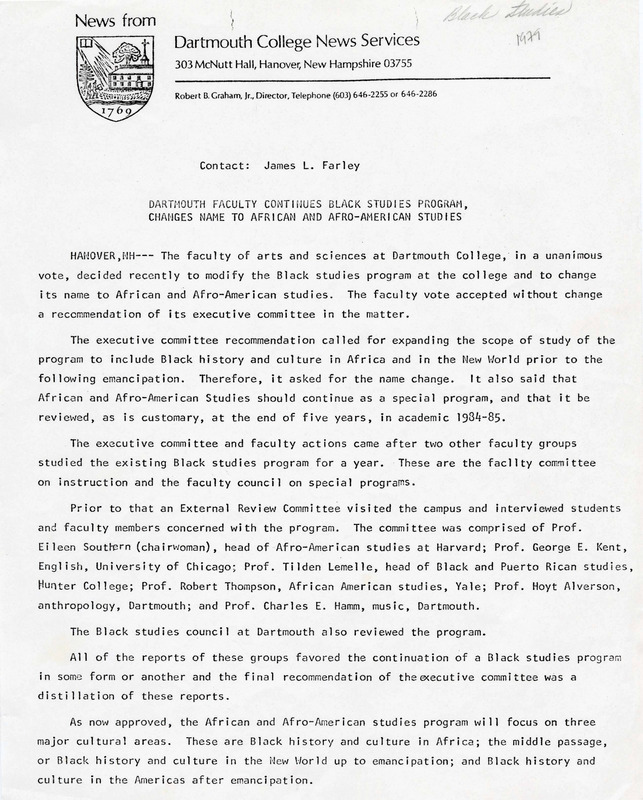

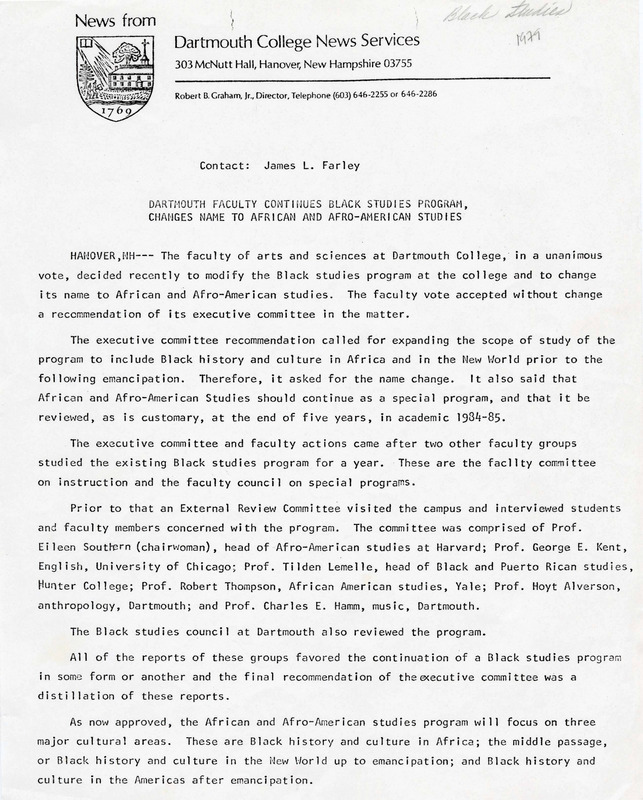

This announcement details the unanimous decision made by Dartmouth College to continue the Black Studies Program for another five years and change its name to “African and Afro-American Studies.” The decision was made after a year-long review by heads of Afro-American Studies at other institutions and Dartmouth’s own Black Studies council. The latter decision to change the program’s name reflected new provisions to “include Black history and culture in Africa and in the New World prior to (and) following emancipation.”

-

Compiled by members of an External Review Committee tasked with evaluating Dartmouth’s Black Studies Program in 1973, this report acknowledges both the weaknesses of Dartmouth’s current program in addition to the valuable role it has played in the lives of several interviewed students. The committee report concludes by asserting that a stronger Black Studies Program “can and must be established at Dartmouth.”

-

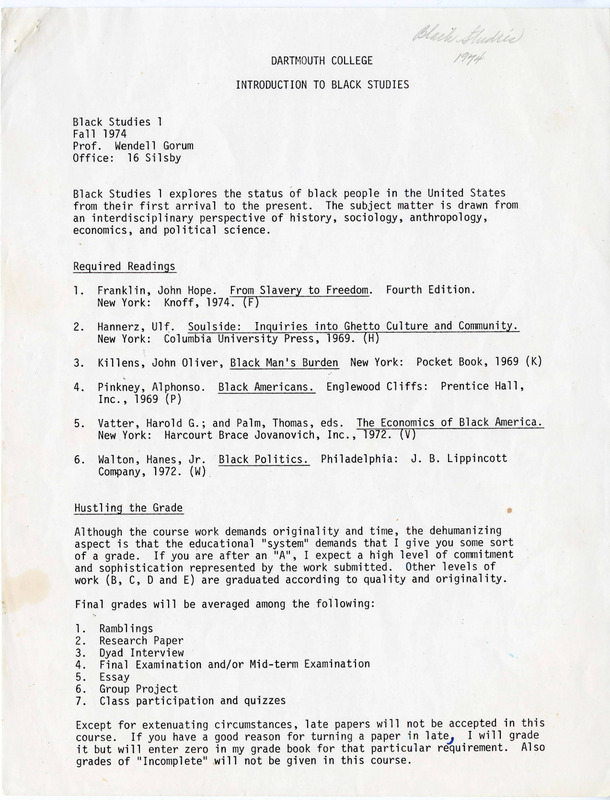

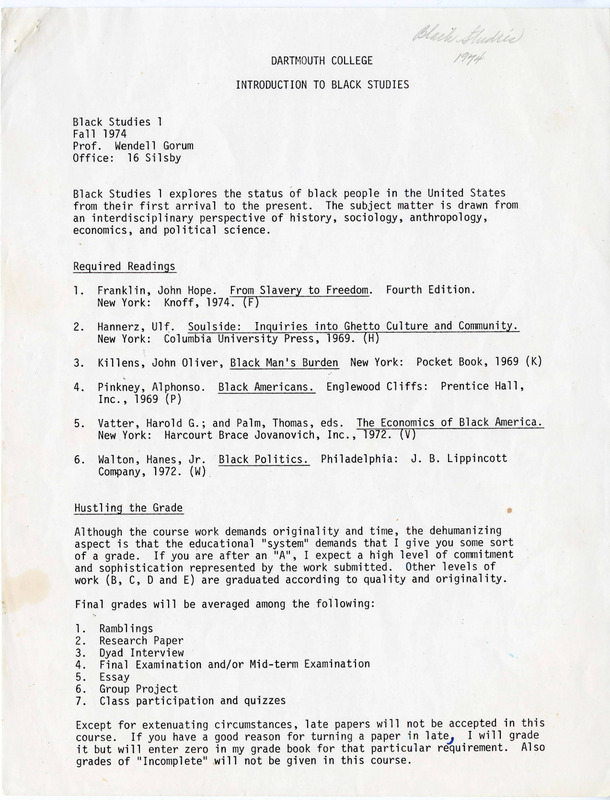

Professor Wendell Gorum’s “Black Studies 1: Introduction to Black Studies” syllabus for the Fall 1974 term. Professor Gorum’s class sought to explore “the status of black people in the United States from their first arrival to the present.”

-

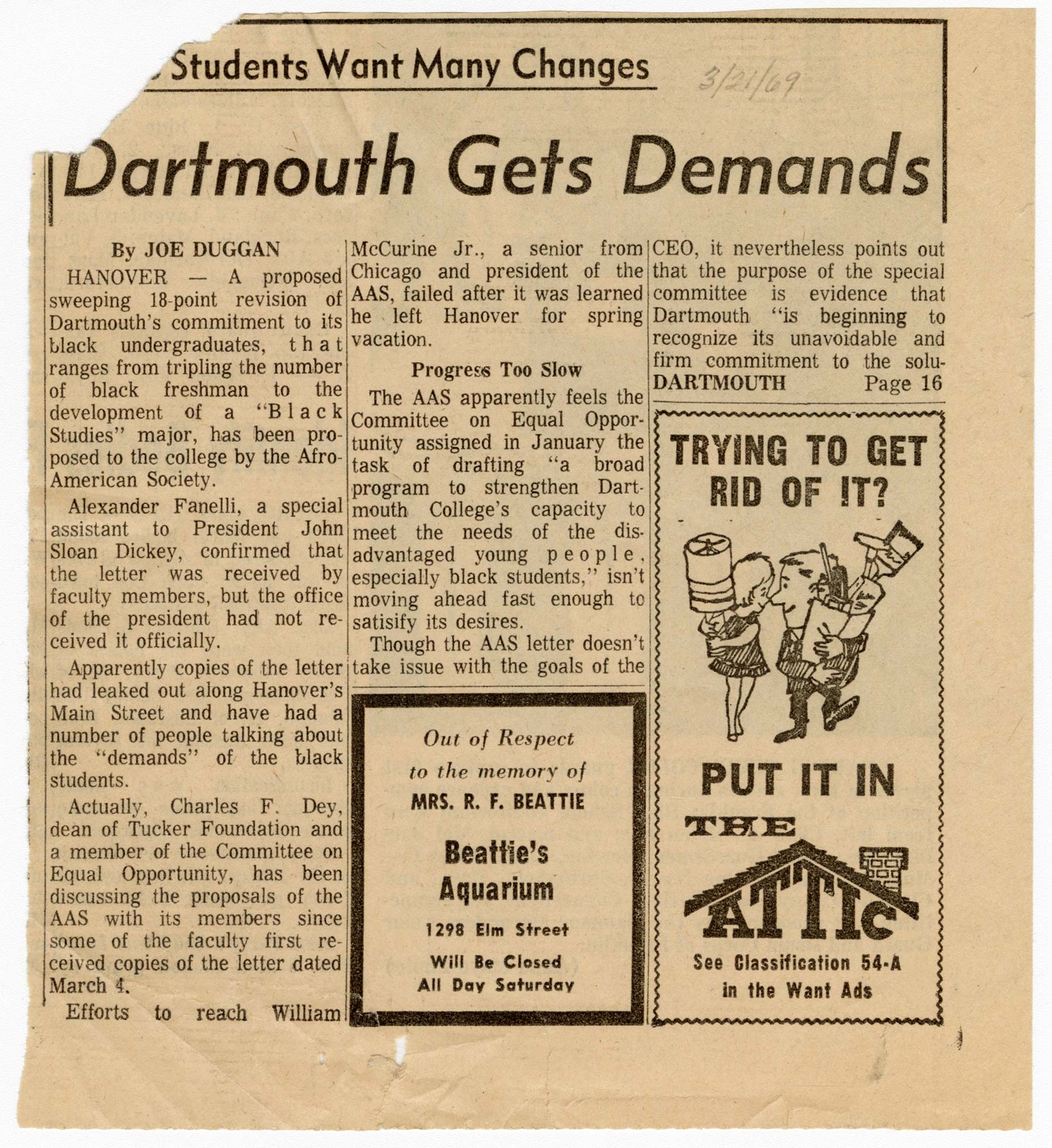

This newspaper article was published following the presentation of demands by Dartmouth’s Afro-American Society (AAS) to the College administration. As author Joe Duggan reports, the 18-point resolution was submitted to College officials primarily to address Dartmouth’s recruitment and admissions policies, including demands for a firm commitment to increasing the percentage of Black students in incoming freshmen classes and Black representation in admissions and guidance departments. In addition to recruitment and advising, the article articulates the students’ other goals, such as a new building to house the Dartmouth Afro-American Society and “the development and implementation of a black studies major by September of 1970.”

-

Admissions Officer Edward T. Chamberlain's notes on equal opportunity recruitment include an appendix with the “three term plan” by students in the Dartmouth Afro-American Society to encourage more Black students to apply to Dartmouth College. The self-appointed Black Student Application Encouragement Committee (BSAEC) outlines costs incurred by student recruiters and recruitment tactics in the form of on-site high school visits, mailed letters and informational packets to prospective students, conference attendance, and calls or meetings with Black students accepted to the College.

-

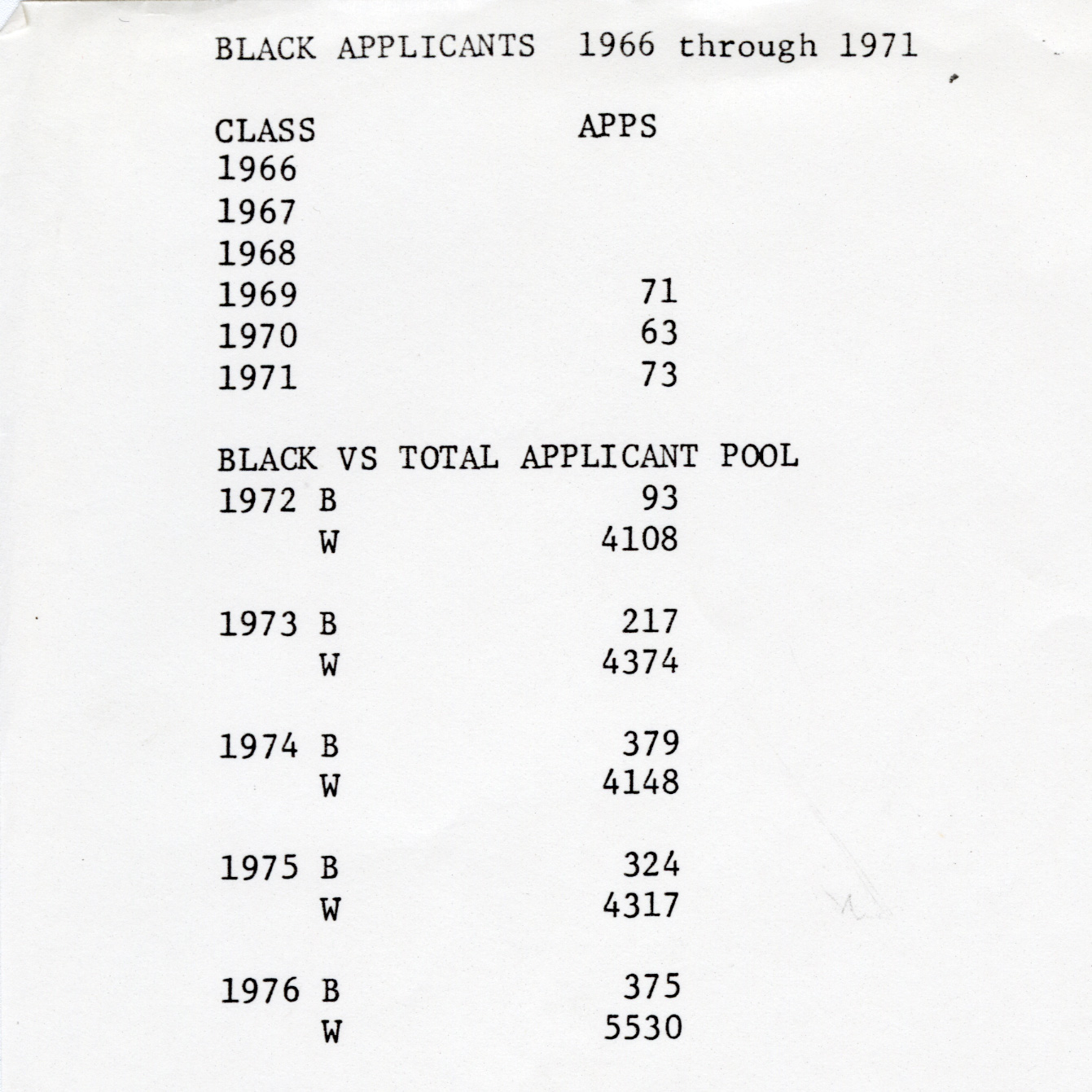

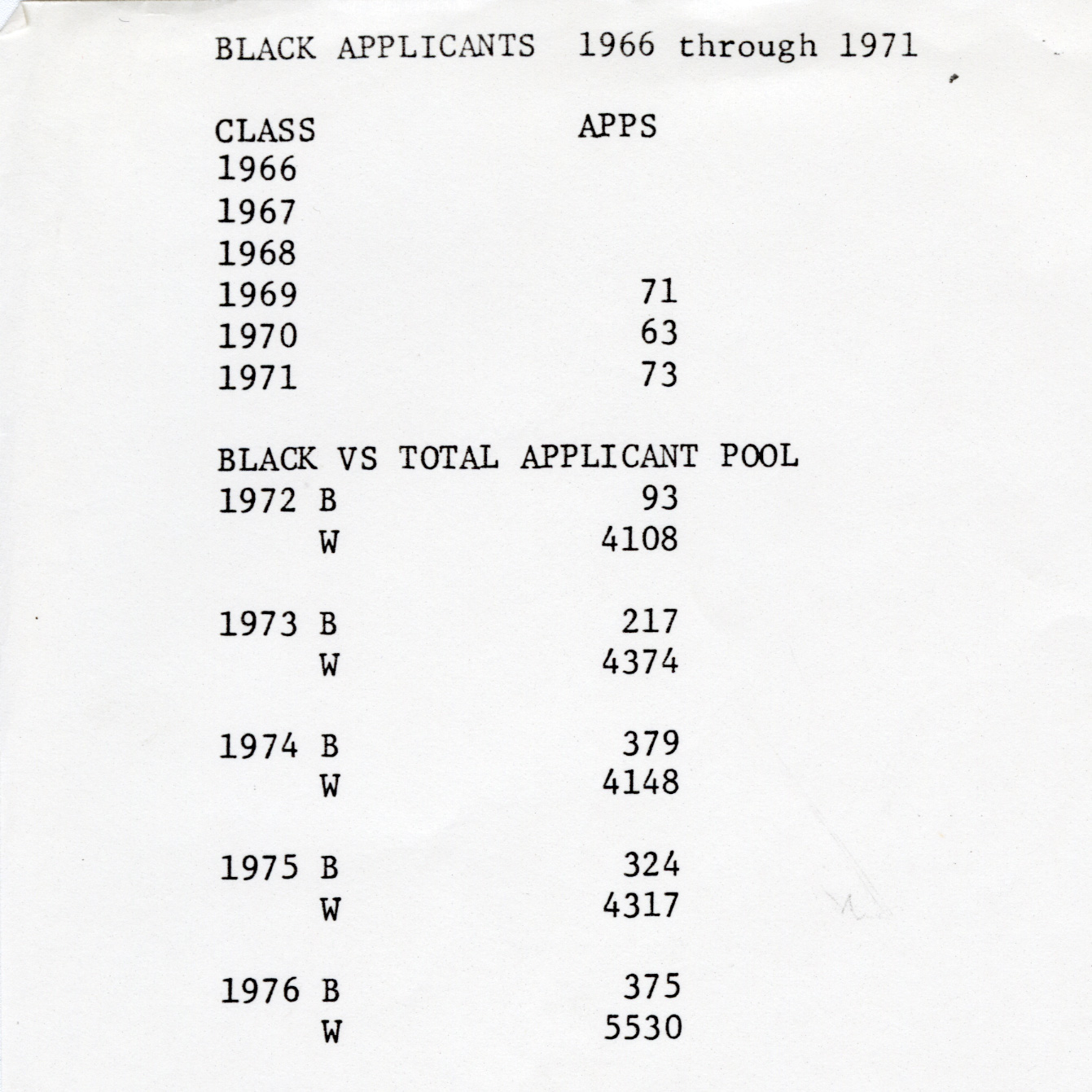

A list of the total number of Black students who applied to, were admitted to, and graduated from Dartmouth College between the years 1966 through 1971. This list demonstrates that even six years following the initiation of the Negro Applications Encouragement (NAE) program, which later became the Black Student Application Encouragement Committee (BSAEC), the number of Black students applying to and attending Dartmouth remained small in comparison to the total number of students throughout the latter half of the 1960s. Based upon the table and hand-written calculations found at the bottom of the page, it appears that an admissions officer was calculating the graduation rate for Black students at Dartmouth.

-

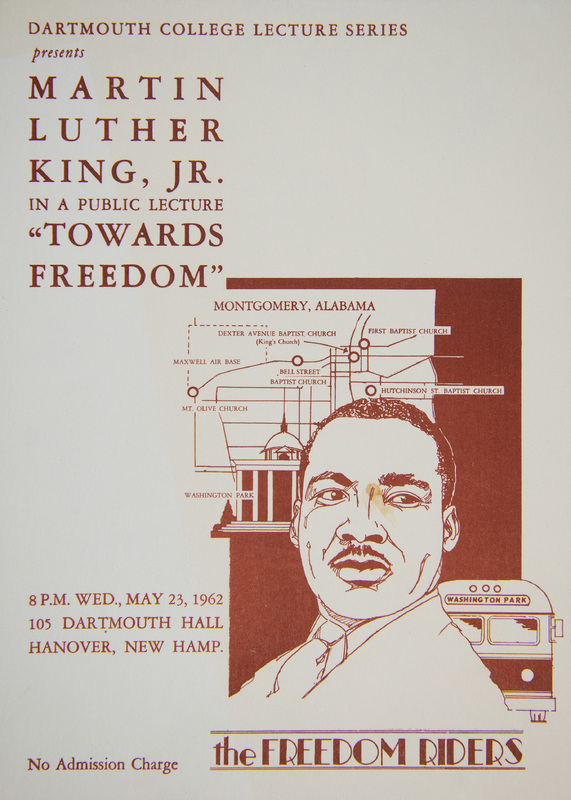

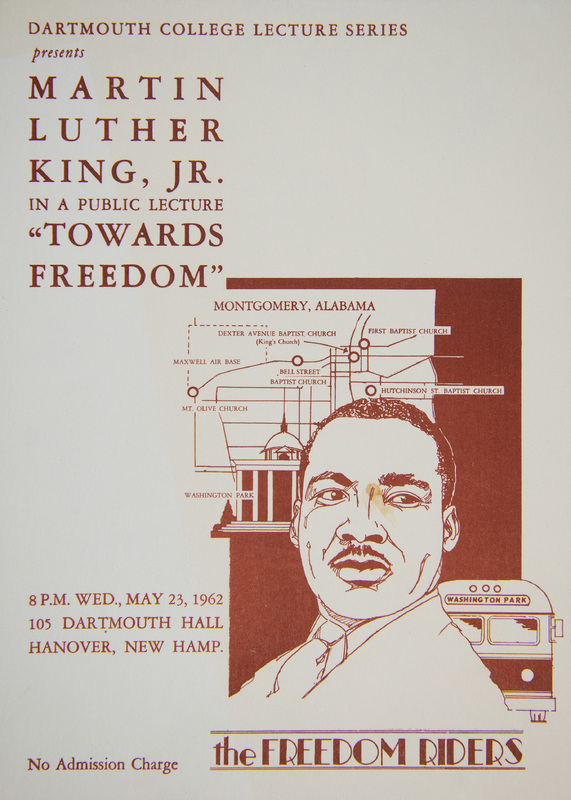

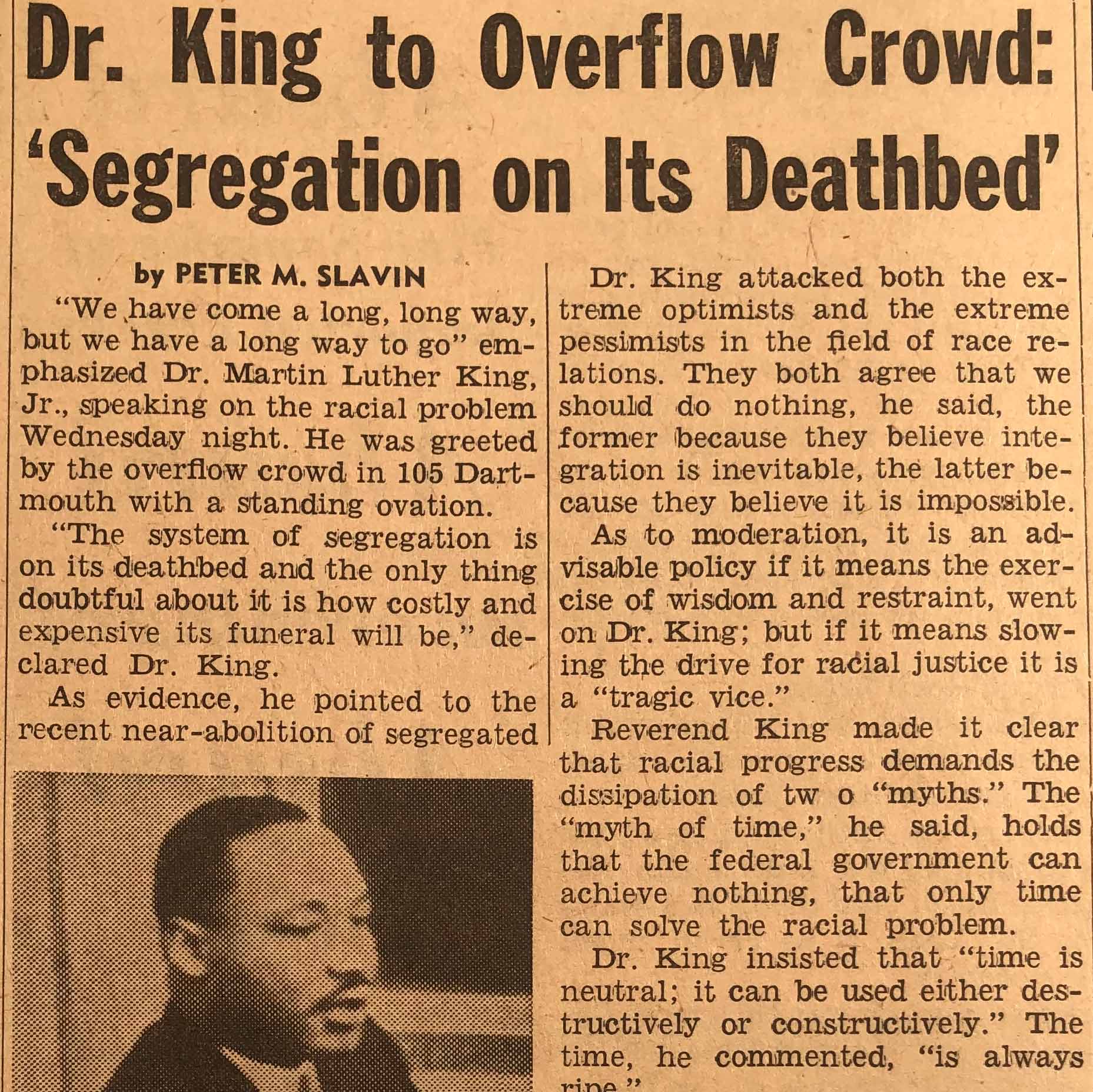

This flyer announces a public lecture to be delivered by Civil Rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on May 23, 1962 in 105 Dartmouth Hall. King’s lecture, which was part of Dartmouth President John Sloan Dickey’s Great Issues Course lecture series, focused on the “question of progress in race relations” in the United States, and called upon community members in the North to take part in the Civil Rights Movement.

-

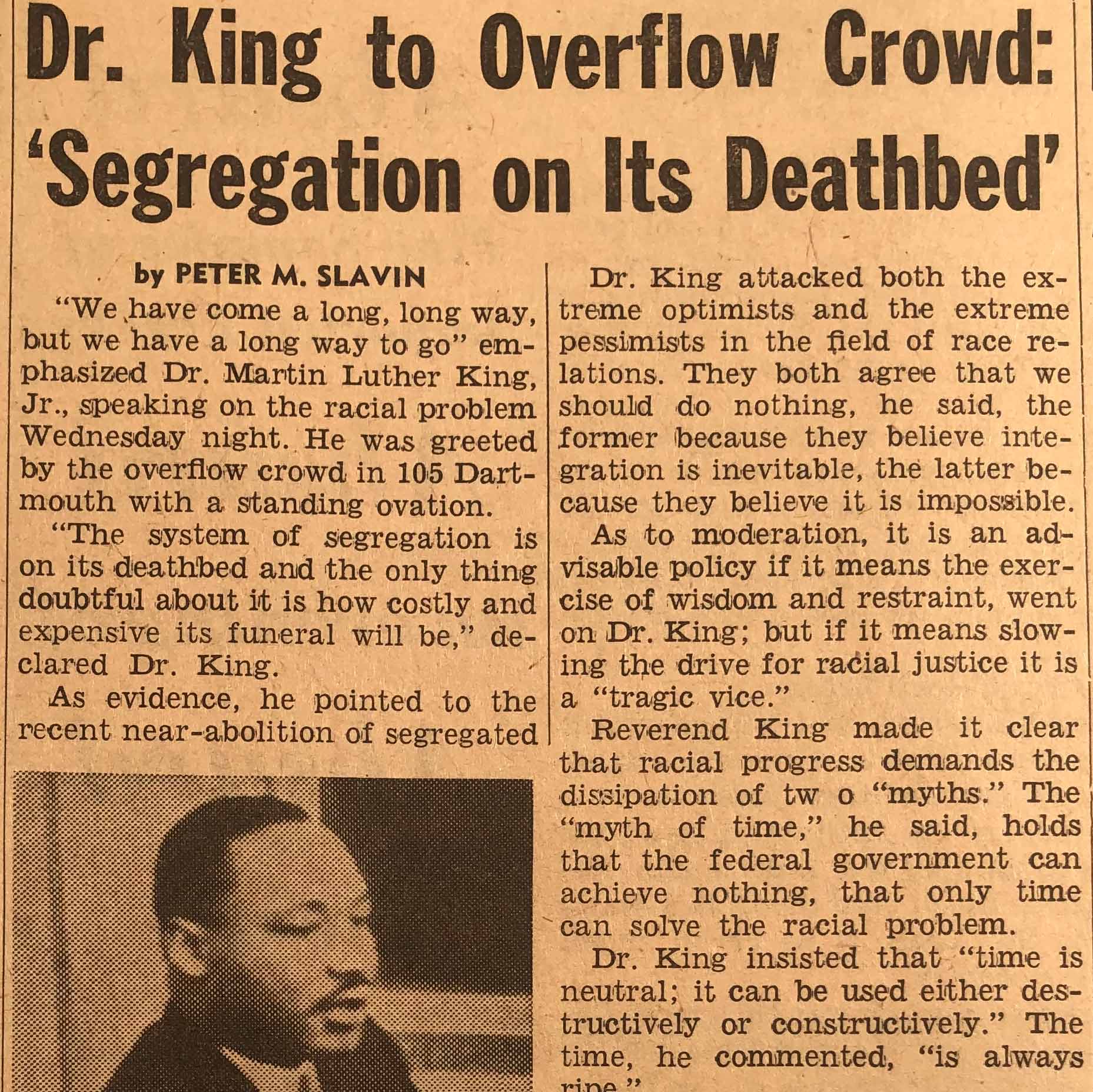

This article summarizes the main points articulated by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in “Towards Freedom,” his Great Issues course lecture. Dr. King stressed the huge disparities in employment and voting rights that still need(ed) to be surmounted by Black Americans despite recent successes in racial equality. He called for wisdom and restraint among Civil Rights activists and underscored the importance of dismantling the myth that only time and education can bring about positive change in racial relations. Lastly, Dr. King urged President John F. Kennedy to issue an executive order declaring all segregation unconstitutional.

-

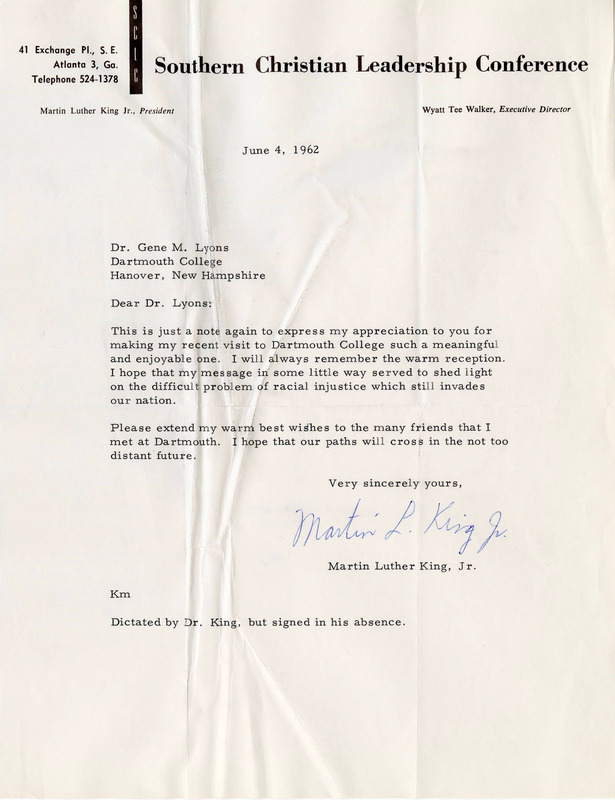

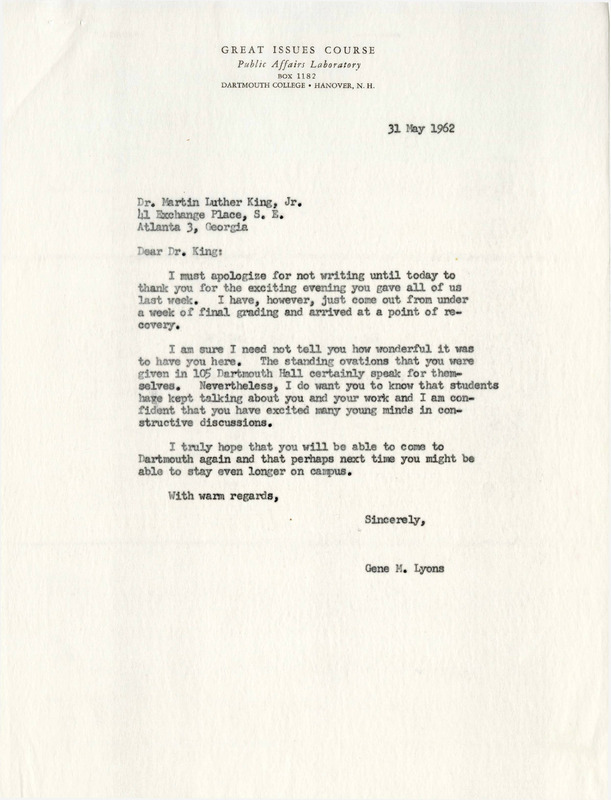

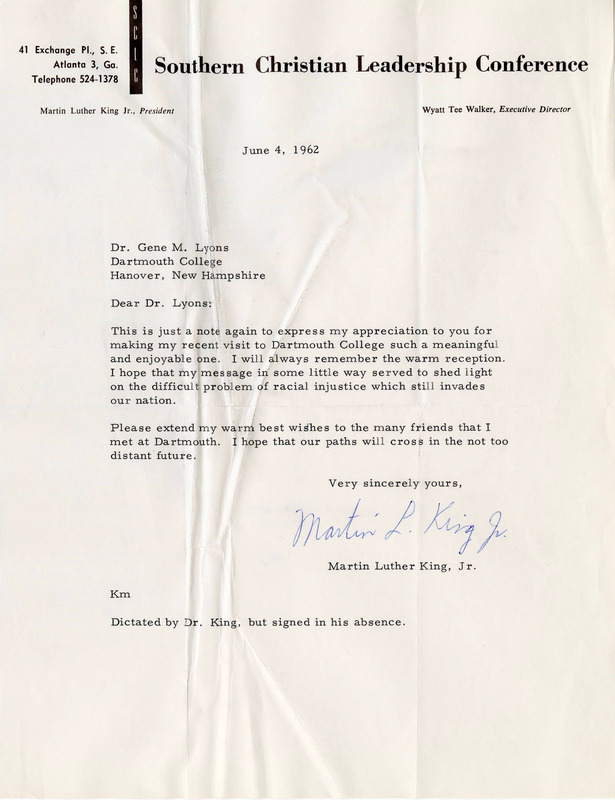

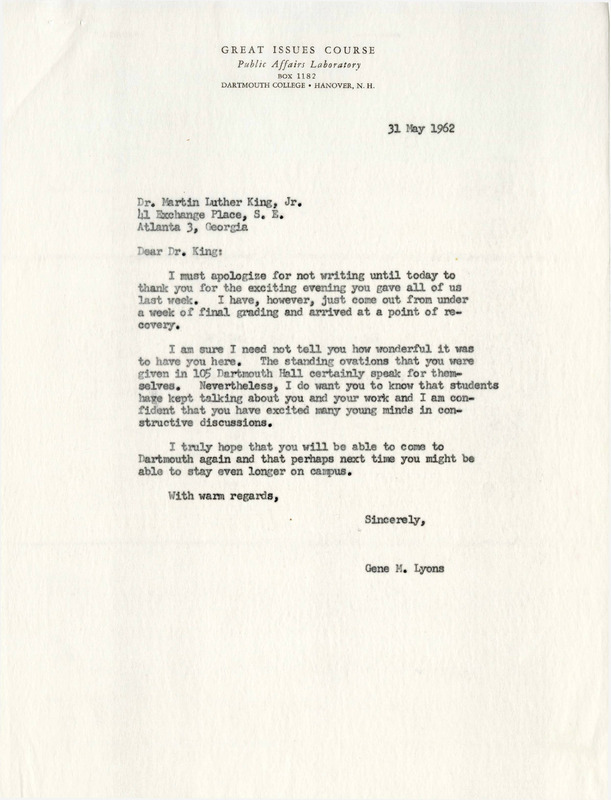

In this letter to Dartmouth Professor Gene Lyons, Civil Rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. expresses his appreciation for the warm welcome he received at Dartmouth and the hope that his lecture "Towards Freedom" shed “light on the difficult problem of racial injustice.” Dr. King concludes by expressing his hopes that he will cross paths with Dr. Lyons in the future.

-

Professor Gene Lyons wrote this letter to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. eight days after the Civil Rights leader visited Dartmouth to deliver an address on the state of the Civil Rights Movement. Lyons apologizes for his delay in sending a letter amid the busy final grading period, and wholeheartedly thanks Dr. King for his visit and empowering words. Lyons concludes by expressing his hope that Dr. King will return and stay for a longer period of time at Dartmouth.

-

A multimedia presentation of the speech the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered at Dartmouth on May 23, 1962.

-

This photo shows the inscription “El Hajj Malik El Shabazz” over the doorway of Cutter Hall. The Afro-American Society proposed officially changing the name Cutter Hall to El Hajj Malik El Shabazz after their move from Lord House, but commissioned the Temple Murals when the College rejected the proposal. The College provided this inscription in the 1980s.

-

Photograph of the El Hajj Malik El Shabazz Center when it was still named Cutter Hall.

-

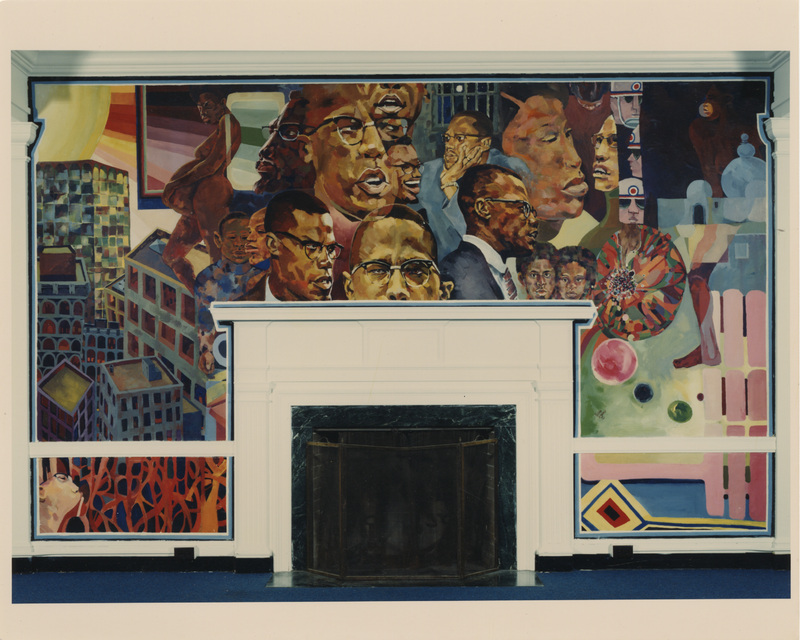

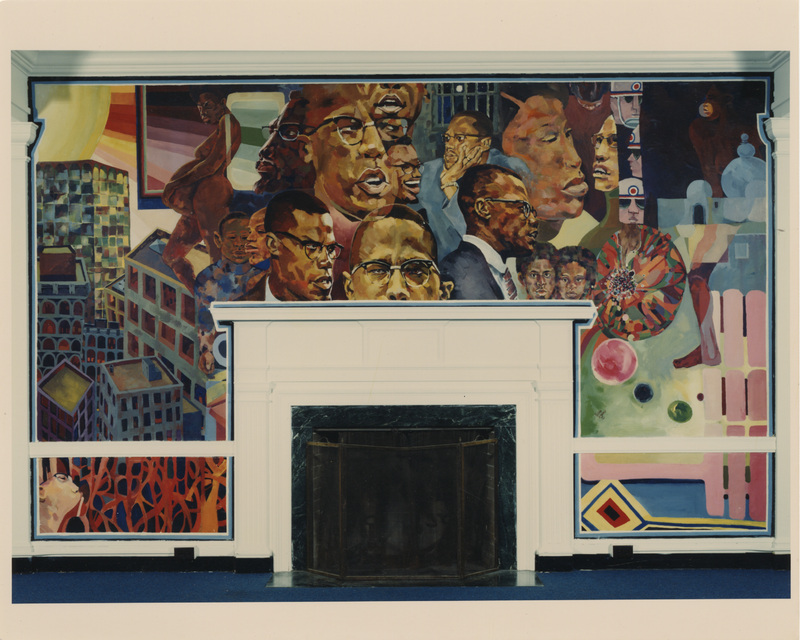

The second acrylic panel The Temple Murals series is located on the left side of the hallway when facing the Shabazz Library in Dartmouth’s Shabazz Center. The panel depicts faces and masks that represent different African cultures, each painted near their geographic point of origin around the shape of the African continent. The sea of faces appears to move toward the viewer like a wave, representing the movement of the African Diaspora. Many faces in the mural were modeled after Dartmouth students on campus in the summer of 1972.

-

This Temple Mural panel honors Betty Shabazz, the wife of Malcolm X, who single-handedly raised their six children following Malcolm’s death. In the panel we see a strong, forward-looking Betty symbolizing hope despite her husband’s untimely death.

-

The fourth panel painted The Temple Murals series, “The Assassination,” greets viewers as they step into the central lounge inside the Shabazz Center at Dartmouth. The panel depicts the turmoil and shock amid Malcolm X’s assassination, beginning a few seconds before he was shot at a rally (only three weeks after visiting Dartmouth). On the right side of the doorway two bodyguards gaze across the rally crowd toward the murderer, who is guided by the only distinctly white figure in the painting.

-

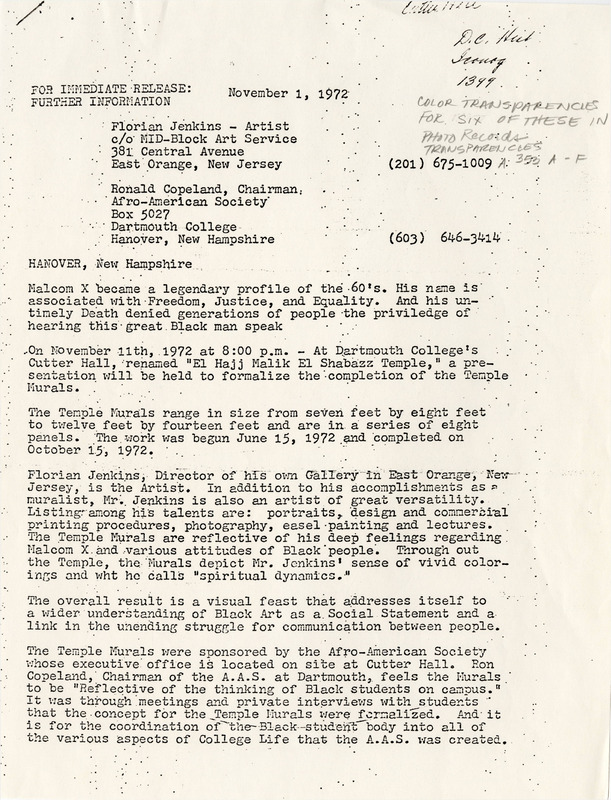

Florian Jenkins painted seven acrylic panels in 1972 for a series called The Temple Murals: The Life of Malcolm X. This panel seeks to full encapsulate Malcolm X as a person, showing Malcolm at varying stages of his life, from a spirit or consciousness to an unborn child, and into childhood and adulthood.

-

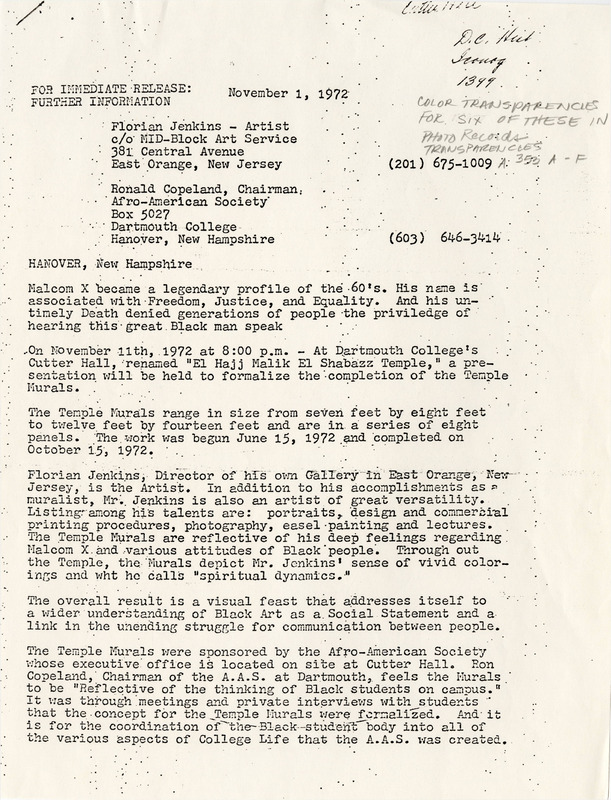

This press release details the upcoming dedication ceremony for the “Temple Murals” painted by artist Florian Jenkins in the newly renamed Shabazz Temple. The Temple Murals are described as a “link in the unending struggle for communication between people,” a depiction of the life and legacy of Malcolm X, and the “thinking of Black students on campus.” The announcement indicates that Jenkins completed the murals only after interviews with Dartmouth students, and that the murals were sponsored by Afro-American Society.

-

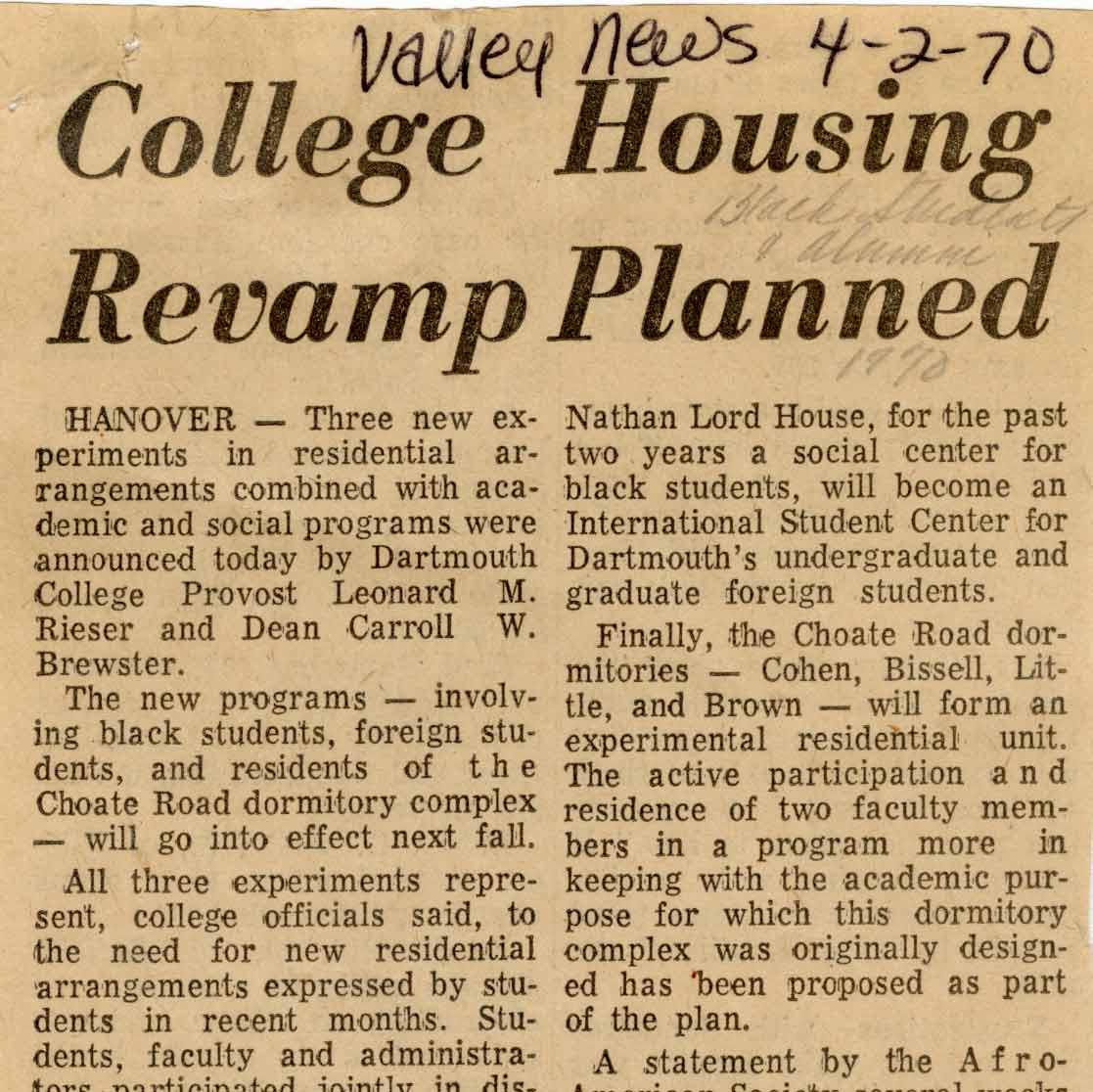

This article reports on the decision made by Dartmouth administrators to designate Cutter Hall as an “experiment in the Afro-American area” in the spring of 1970, upon the request of the Afro-American Society and the Committee on Equal Opportunity. Cutter Hall was initially used as a residential unit for Dartmouth students interested in international affairs, but was transformed into a residential space for 35 Black students including “freshmen in urgent need of special counseling, undergraduate tutors... [and] students who plan to take Black Studies courses.” In addition to serving as a residential hall, Cutter Hall would replace Lord House as the “social and cultural center for black students and provide office space for the Afro-American Society” beginning in Fall 1970.

-

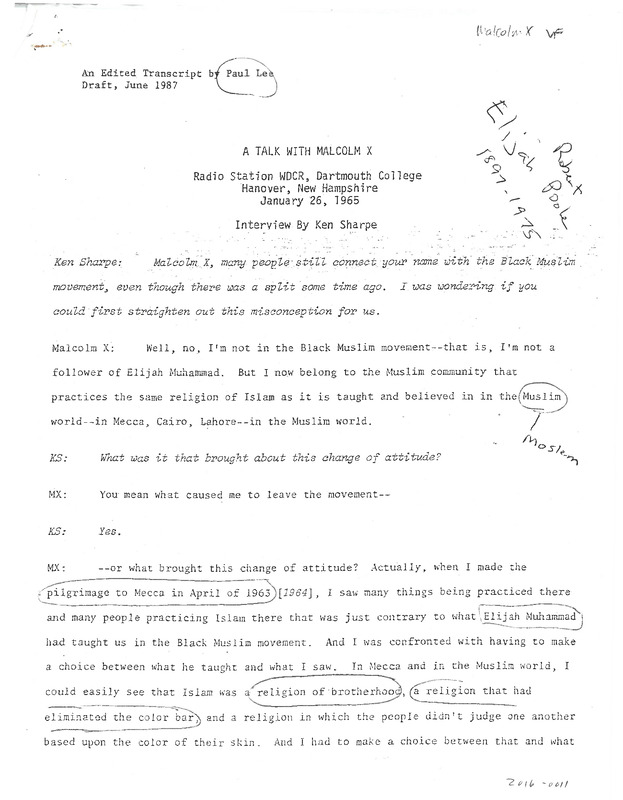

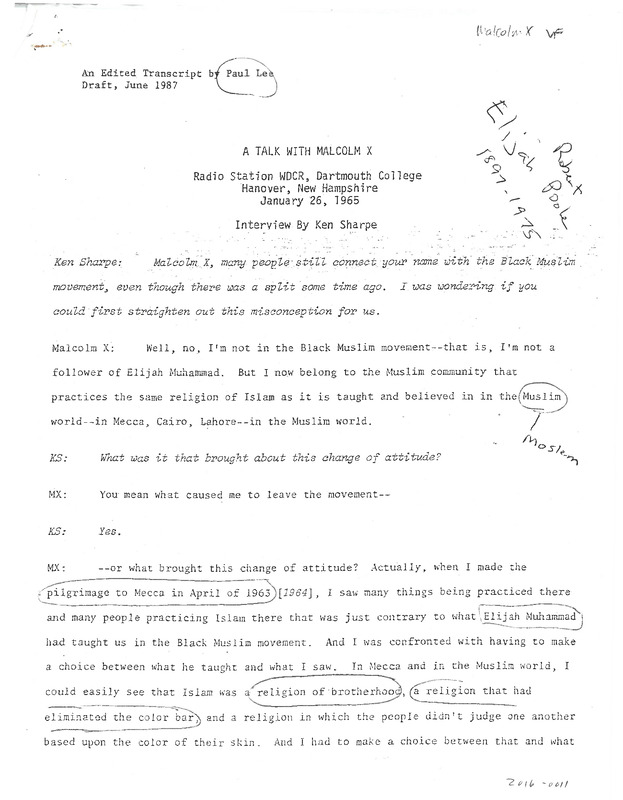

An edited transcript of Ken Sharpe's WDCR interview with Malcolm X on January 26, 1965.

-

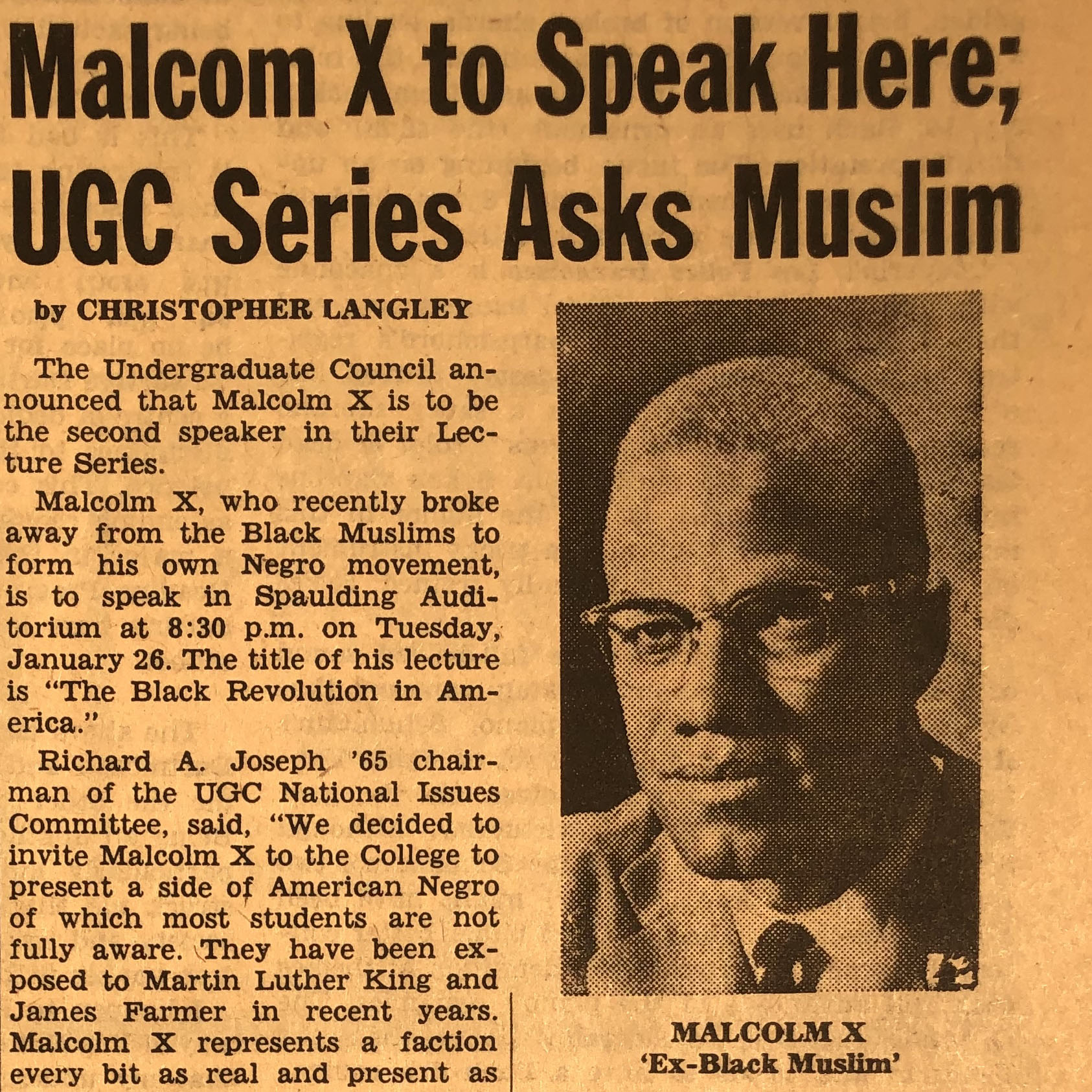

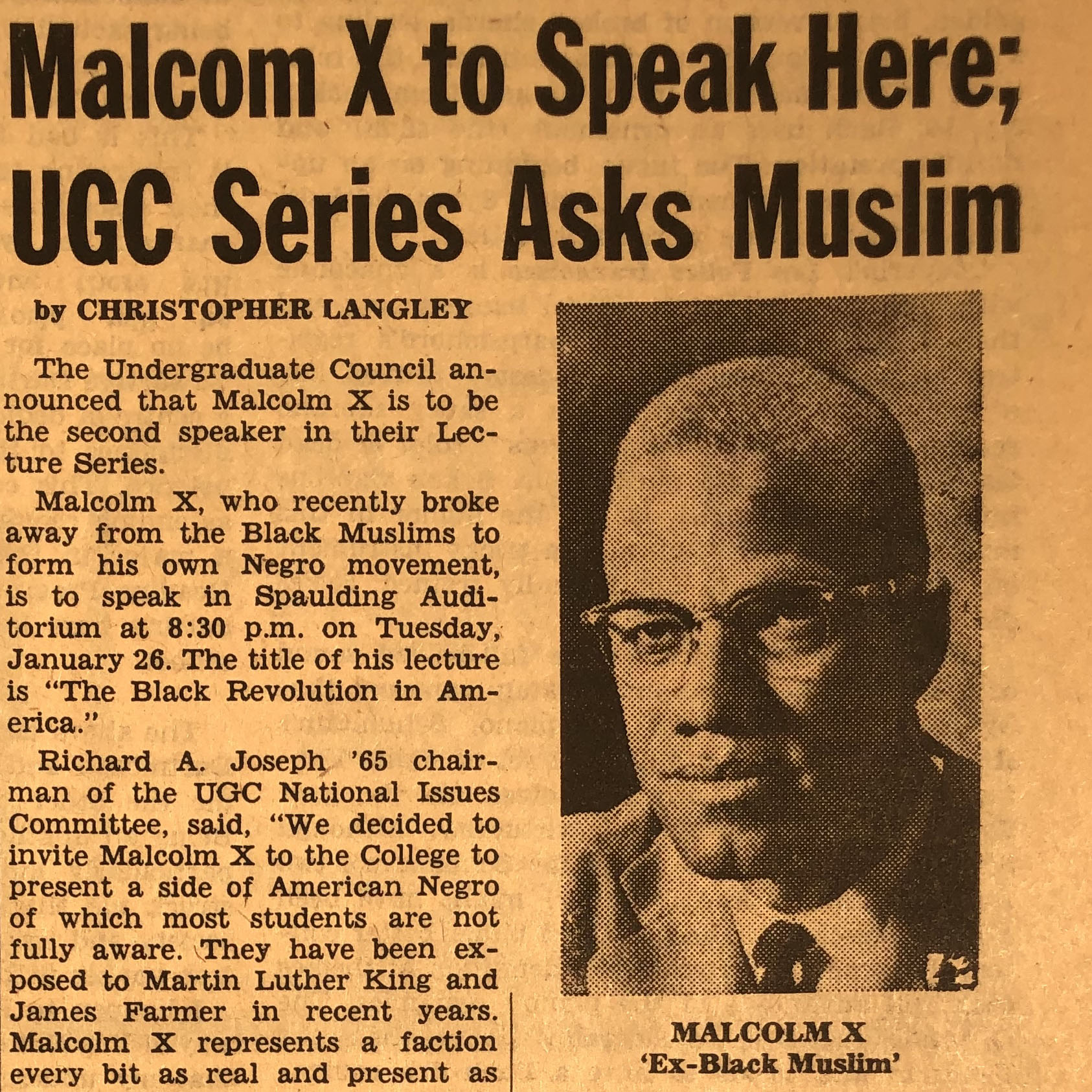

Student reporter Christopher Langley announces that the Undergraduate Council (UGC) has invited Malcolm X to be the second speaker in their 1965 lecture series at Dartmouth College. Richard Joseph describes the decision to invite Malcolm as a way to “present a side of [the] American Negro of which most students are not fully aware” in contrast to previous speakers Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and James Farmer. Langley details Malcolm X’s recent break with the Black Muslims, his trip to the Middle East, and the role of Dartmouth senior Ahmed S. Osman in convincing Malcolm X to come to campus as a speaker.

-

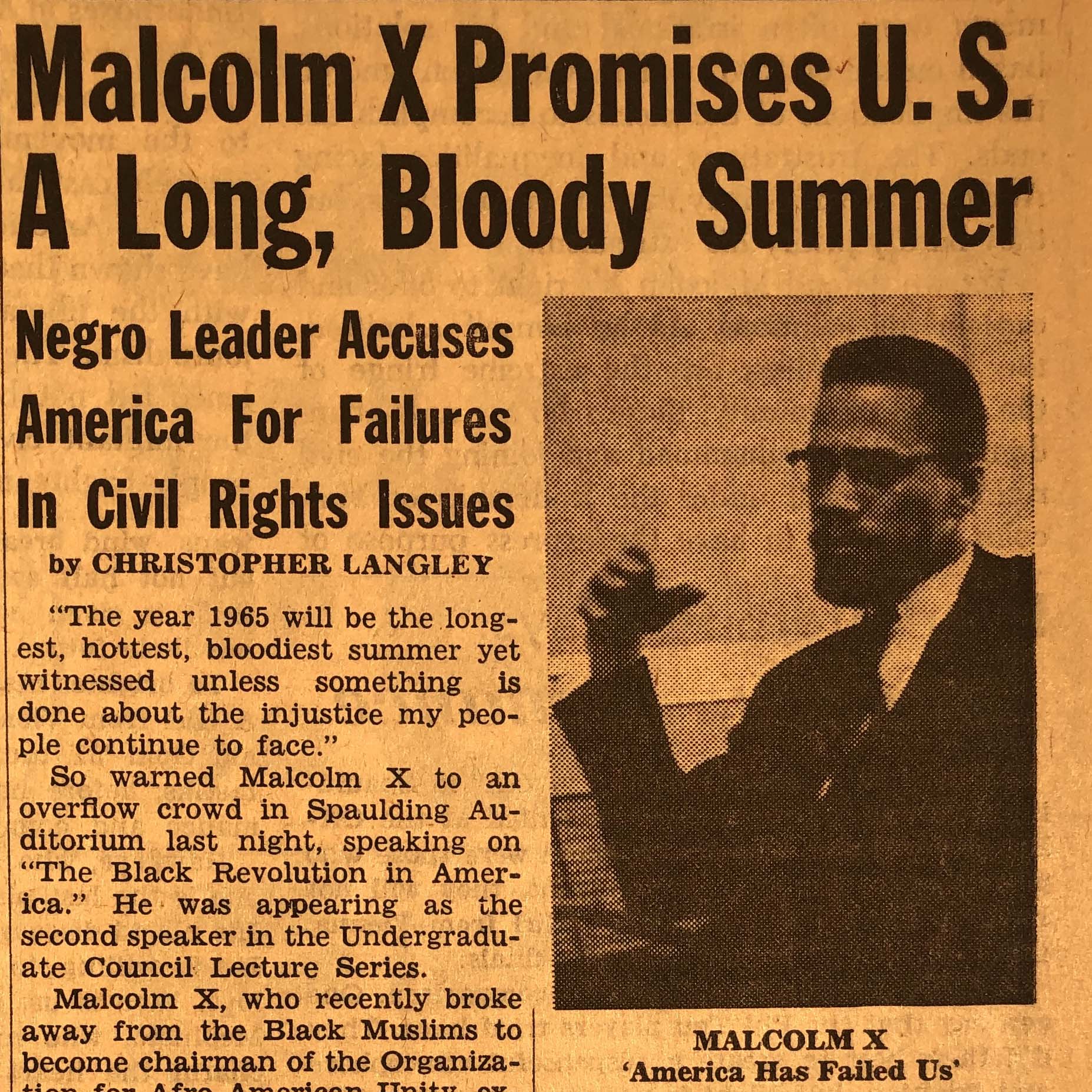

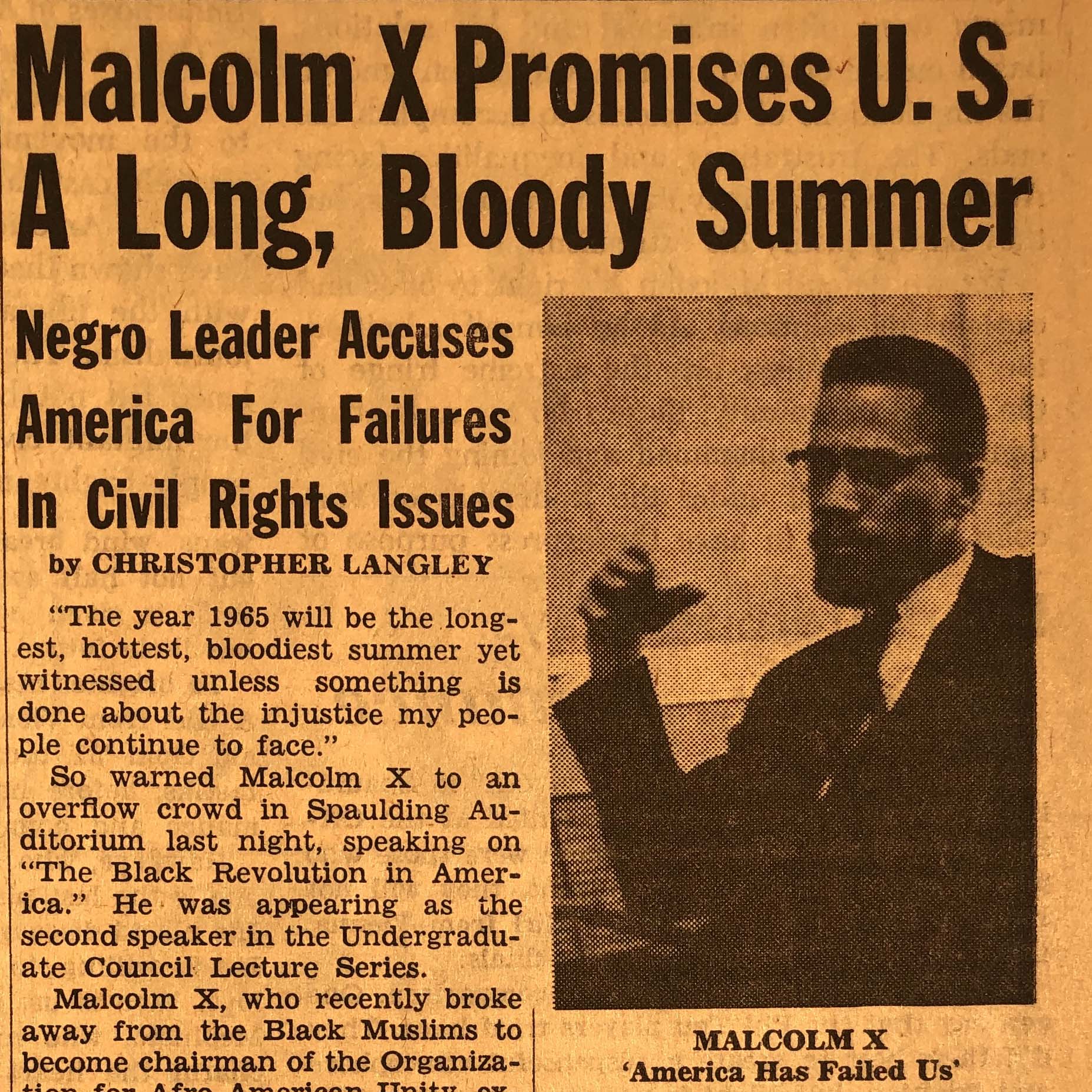

Published a day after Malcolm X’s Dartmouth address, “The Black Revolution in America,” this article by Christopher Langley summarizes the main points Malcolm made regarding race relations. Malcolm emphasized the international nature of the “race problem,” the importance of concentrating on areas of accord between U.S. freedom movements, the influence of African nationalism in strengthening the Black revolution in America, and the role of biased press and “a racist government in Washington” in the failure to resolve Civil Rights issues.

-

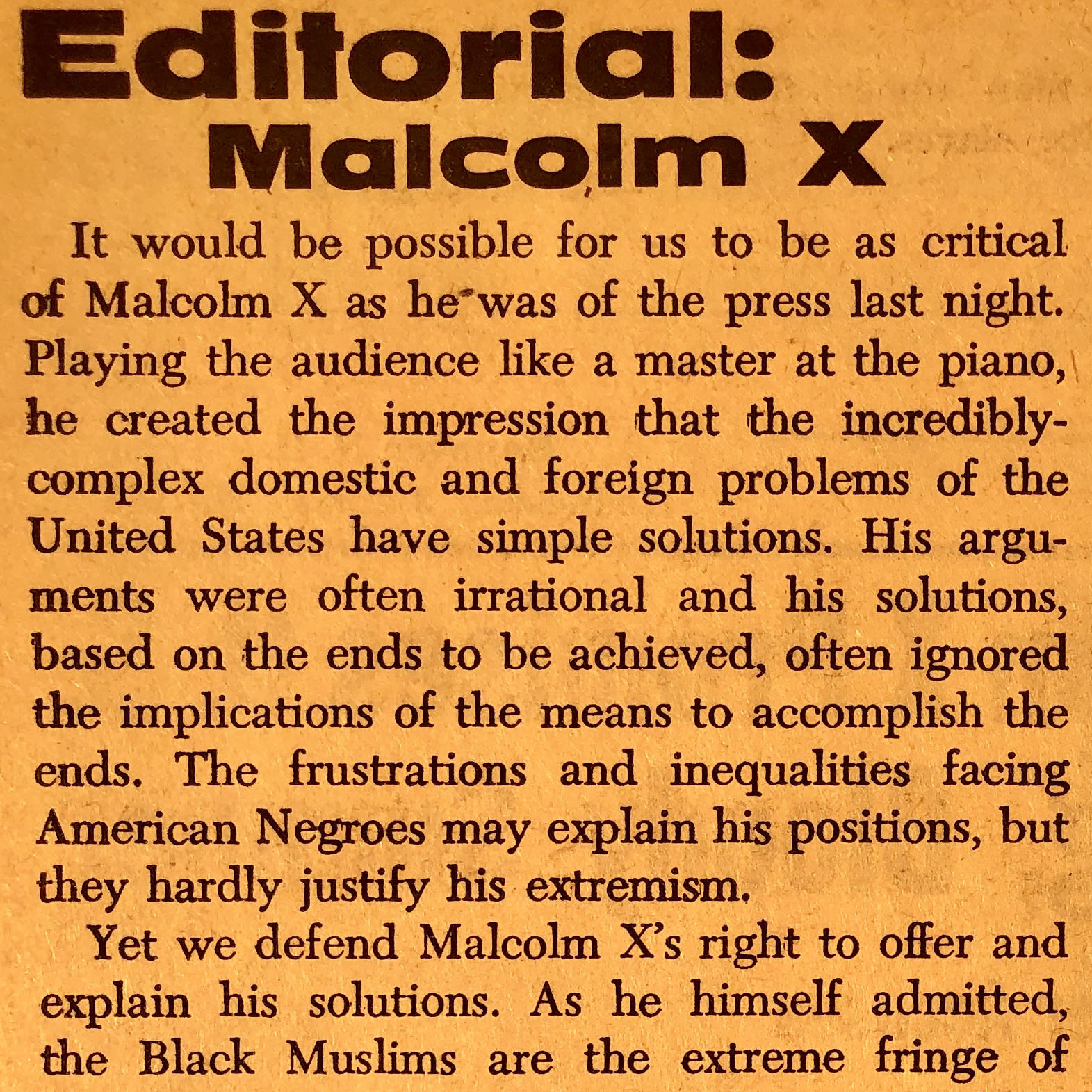

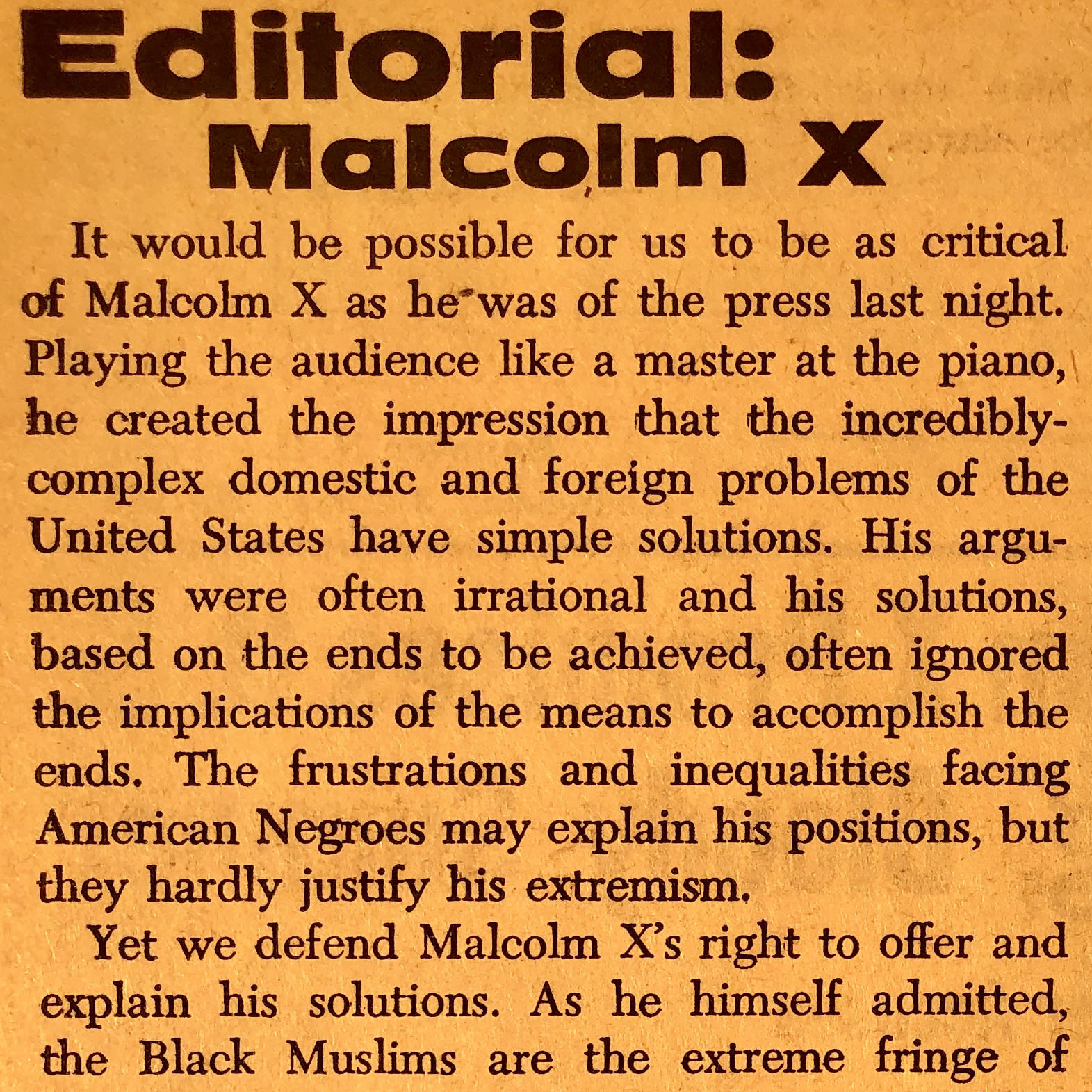

This response to Malcolm X's visit to Dartmouth critiques the "extremism" of Malcolm X and the Black Muslims as fringe participants in the Civil Rights Movement. While the author defends Malcolm X's right to put forth his arguments, they choose to praise him and his followers for liberalizing the movement, thereby normalizing "moderate" groups with achievable goals, such as the NAACP, CORE, and Urban League.

-

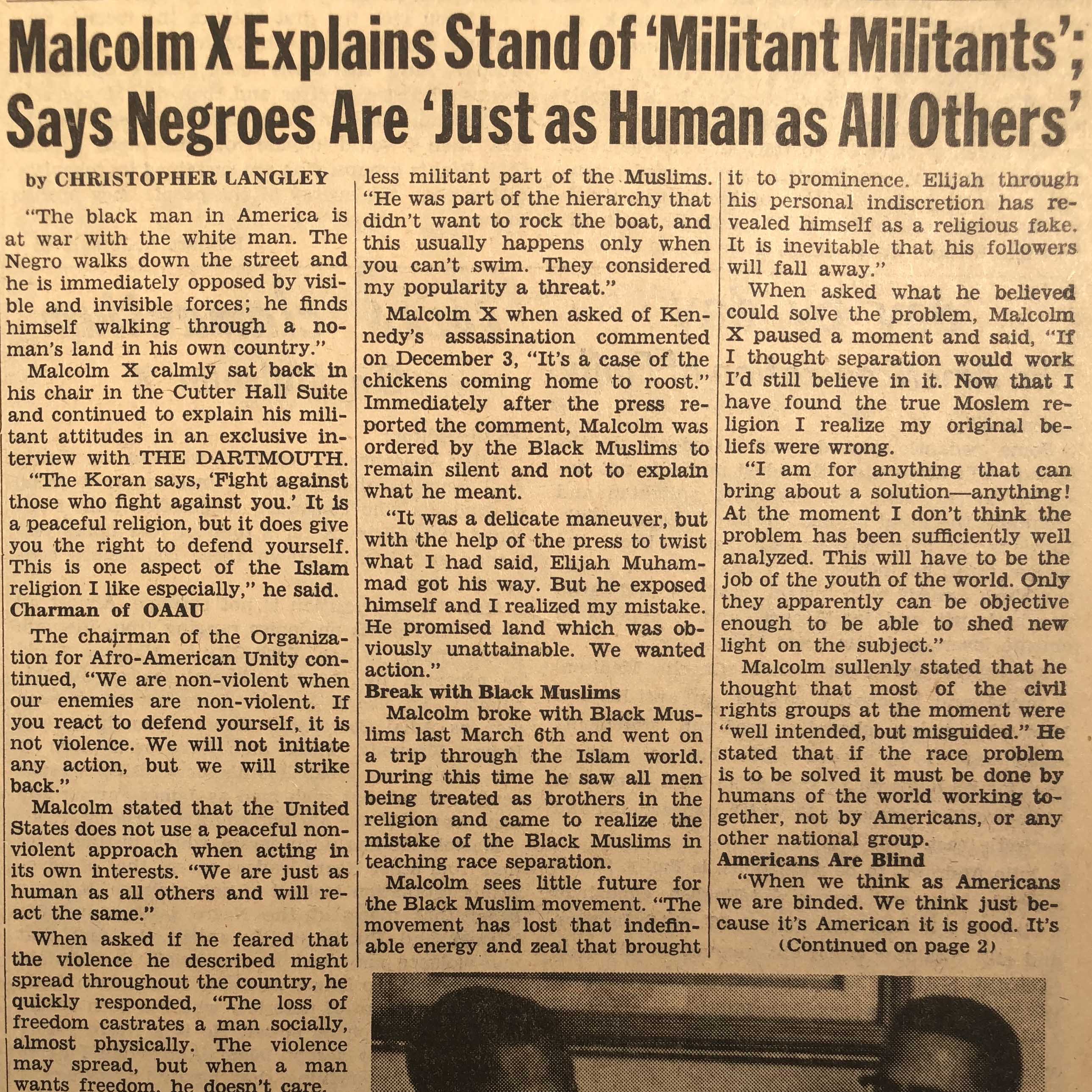

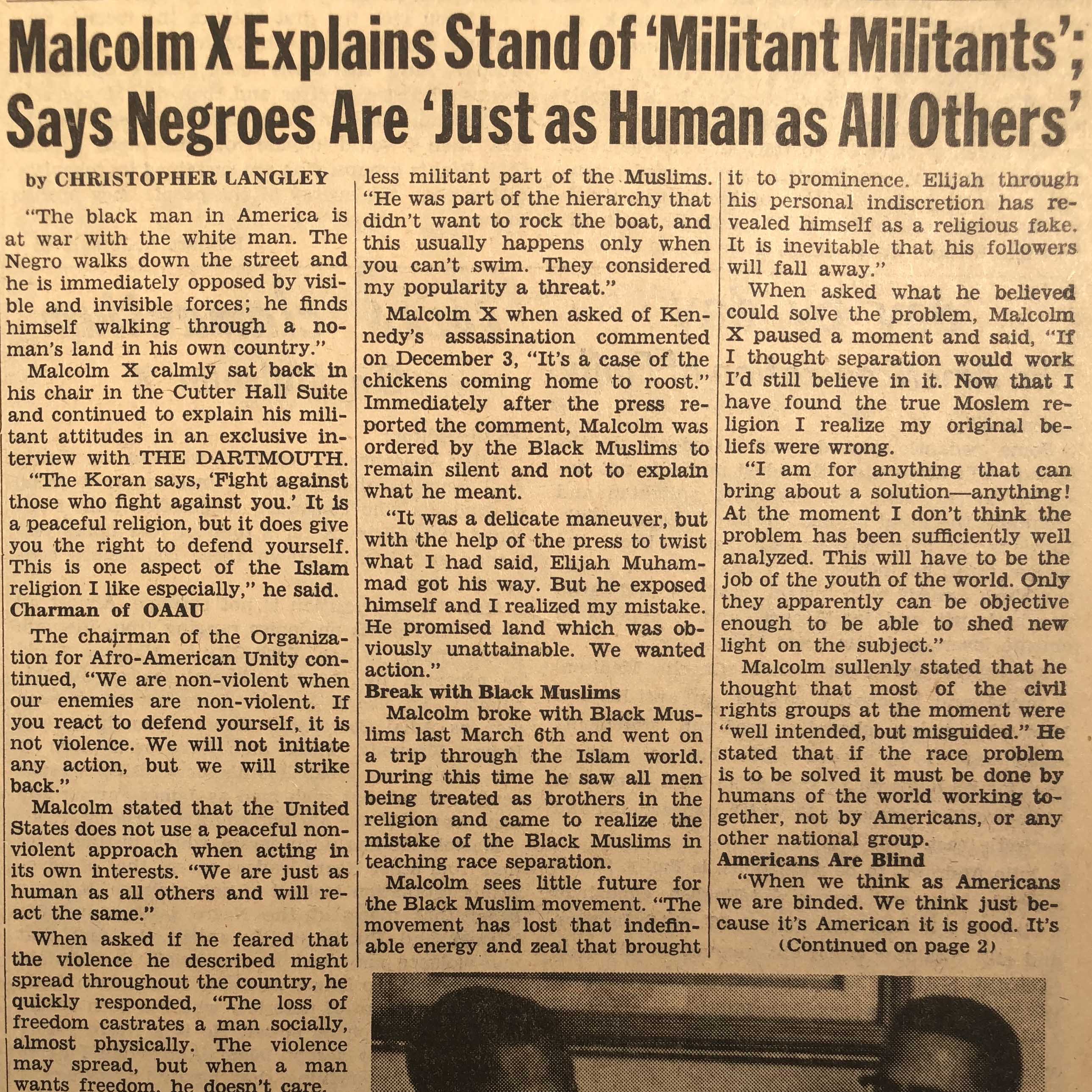

In this exclusive interview for Dartmouth’s student newspaper, Malcolm X explains the inspiration he derives from his Muslim faith, why he broke with the Black Muslim movement, why he believes American Civil Rights groups are “well intentioned, but misguided,” and his work with the Organization for Afro-American Unity.

-

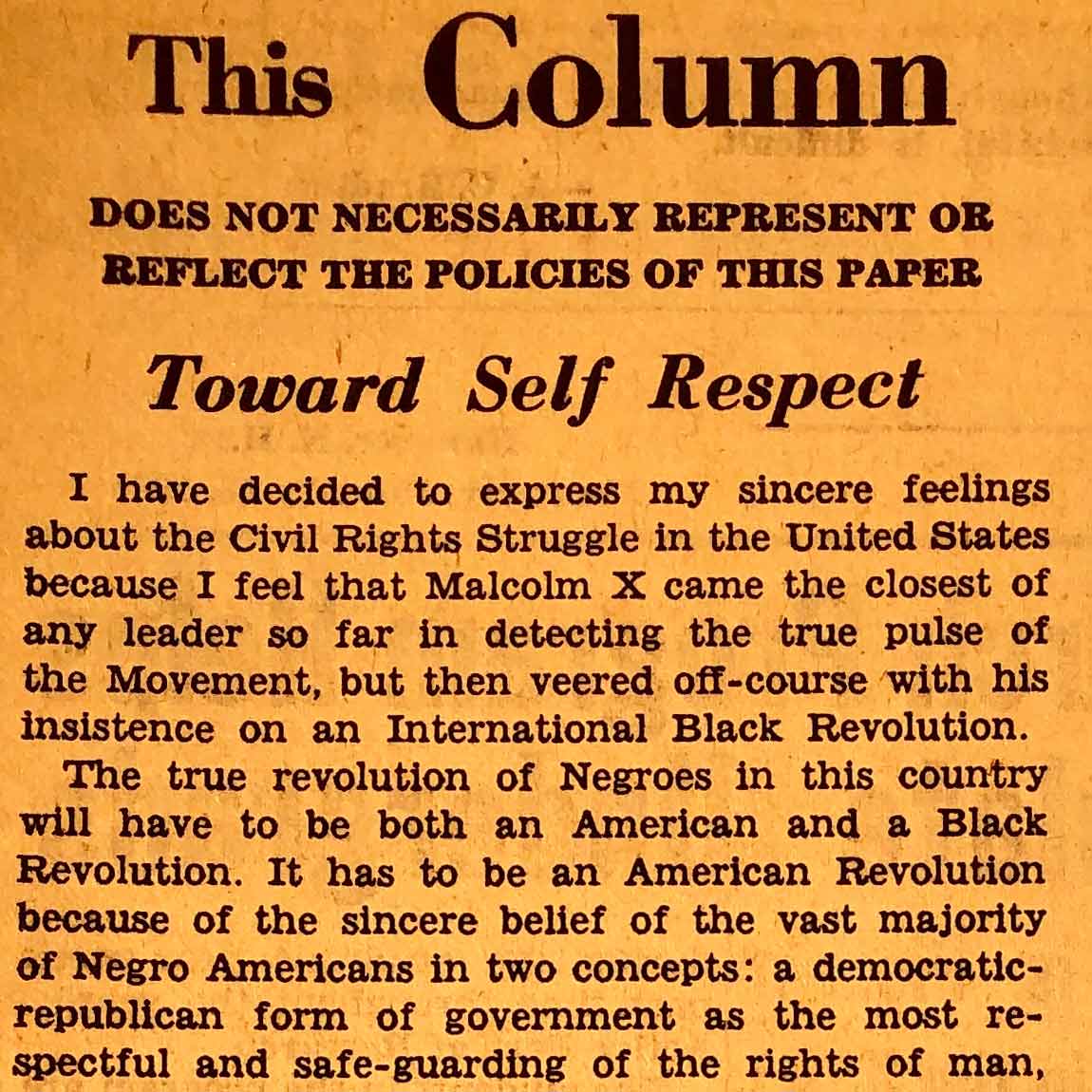

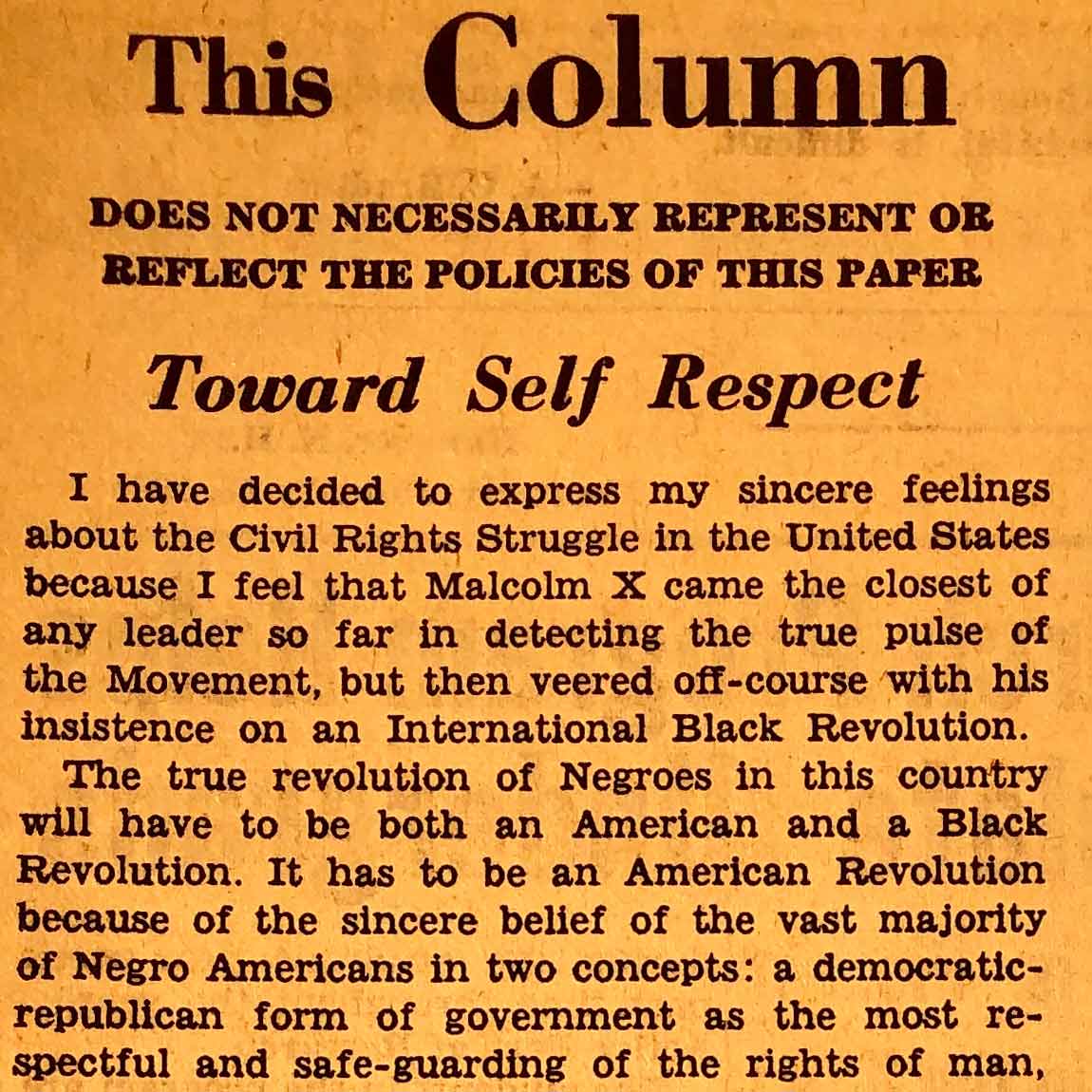

Richard Joseph '65 posits that the "true revolution" of Black Americans must be an American revolution and a Black revolution. He asserts that the first step of this true revolution is for Black Americans to be "self-respecting" and proud of their heritage. The second step of this revolution is for American society to foster participation from all its members regardless of race.