The Curriculum Expands

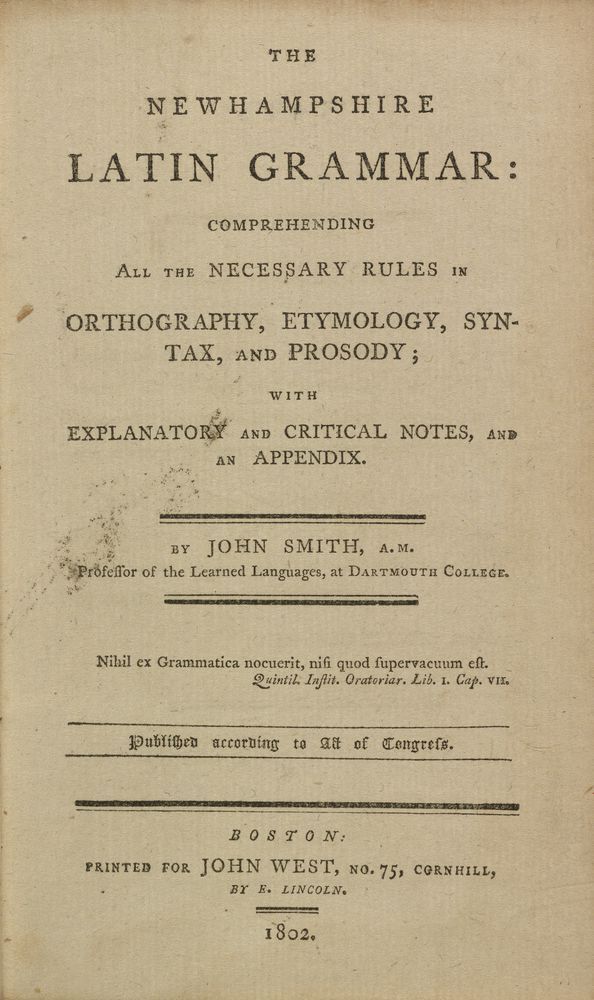

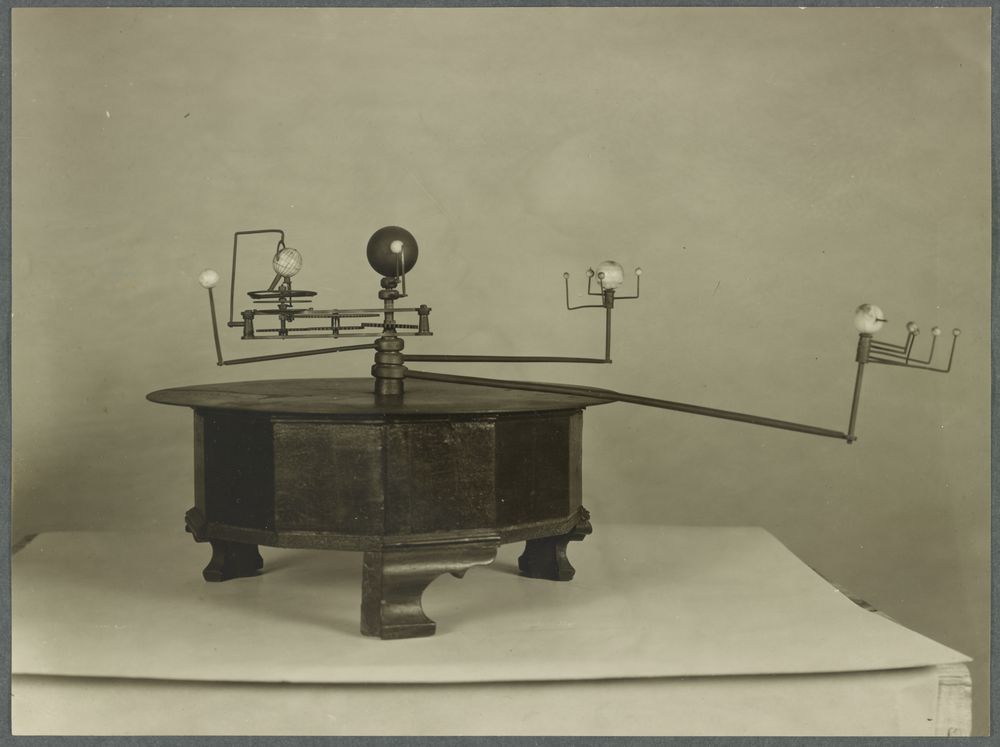

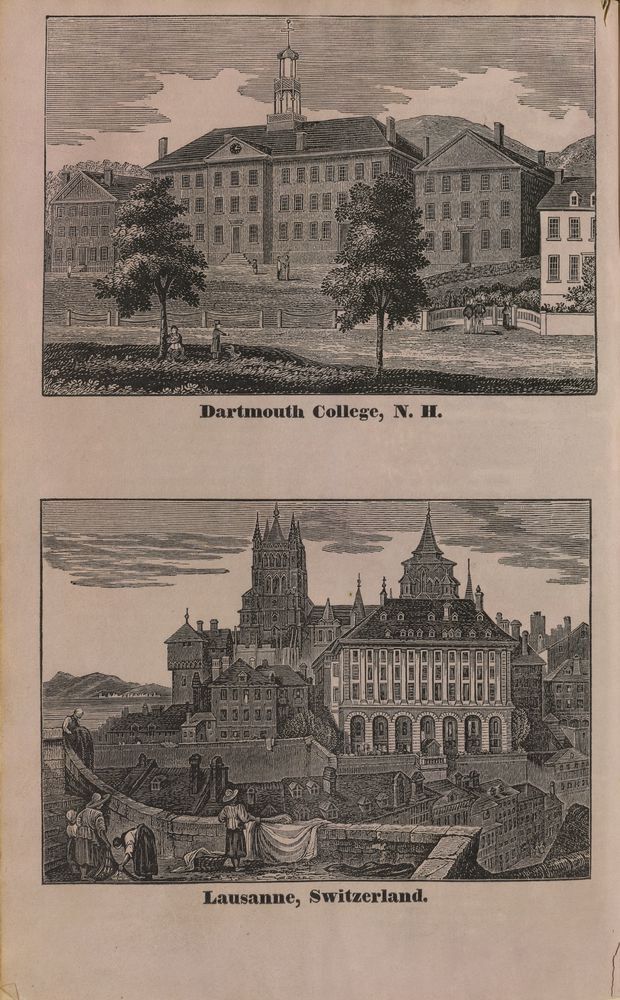

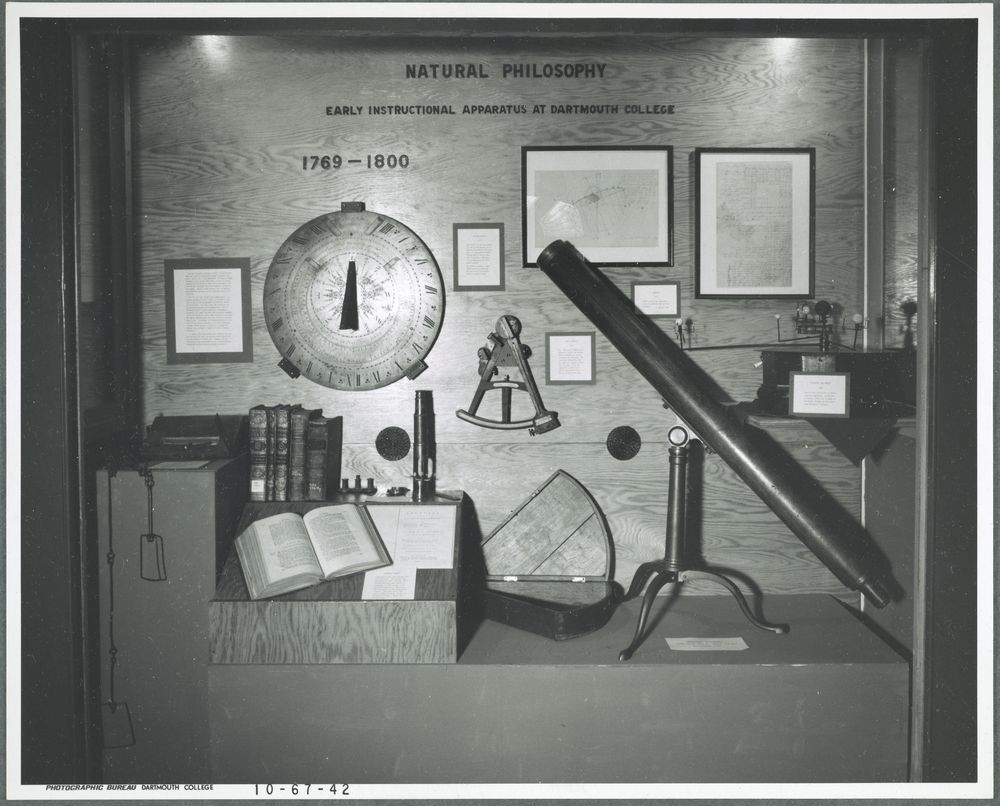

In 1793, Massachusetts Magazine described a flourishing Dartmouth College with three faculty members: one each in history, languages, and natural philosophy. President John Wheelock, the successor to his father, also served as professor of history. More than a quarter of the College’s graduates had pursued religious vocations. With a durable undergraduate curriculum in place for humanities based courses, other fields, notably the sciences, would soon specialize and elaborate. How some professors taught changed little for more than a century. Recitation, rote memorization, and understanding of canonical texts were still at the center of learning. Little else was static.

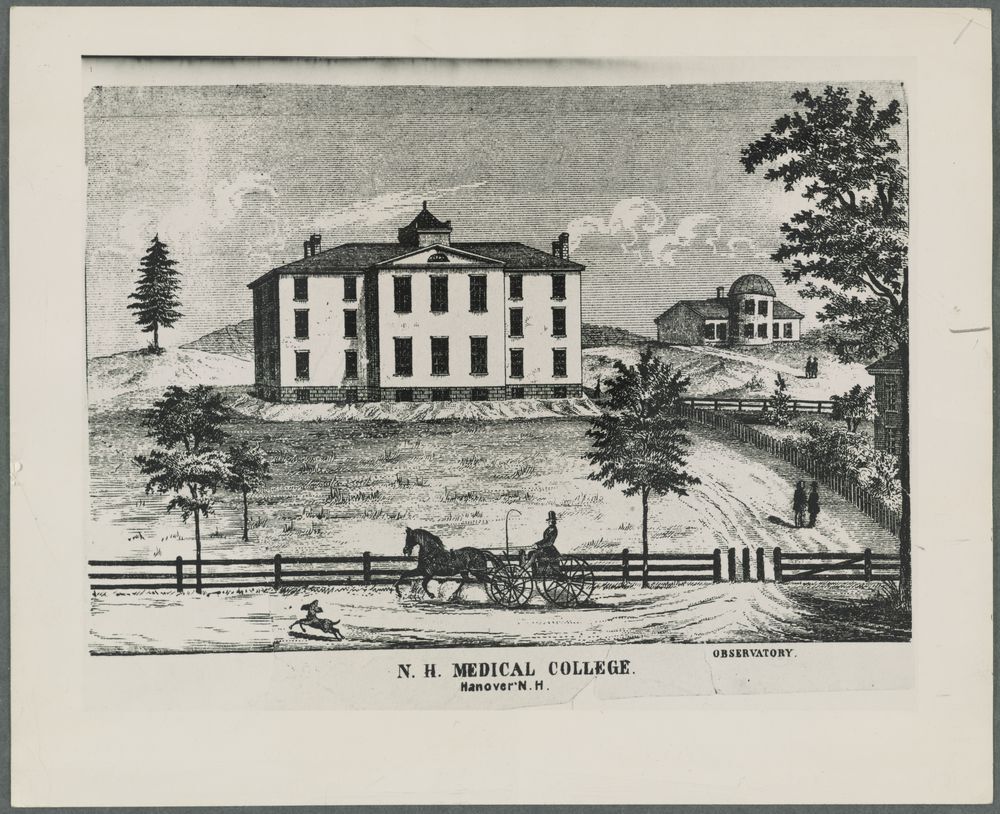

In just more than a century, Dartmouth added professional schools in medicine (1797), engineering (1867), and business (1900). Each vocational school spoke to specialization and the growth of disciplines; they also participated in a unique dialogue between the professional education and the liberal arts at Dartmouth. Antebellum students and faculty also applied their critical capacities to public life. Beyond the campus green, students and faculty took up religious revivals, debated solutions to slavery, including abolition and colonization, addressed alcohol and temperance, and even adopted vegetarianism as a moral, physical, and spiritual good.

Previous: What the Liberal Arts are, or Ought to Be -- Next: Liberal Education in an Age of Innovations