The New Hampshire Case

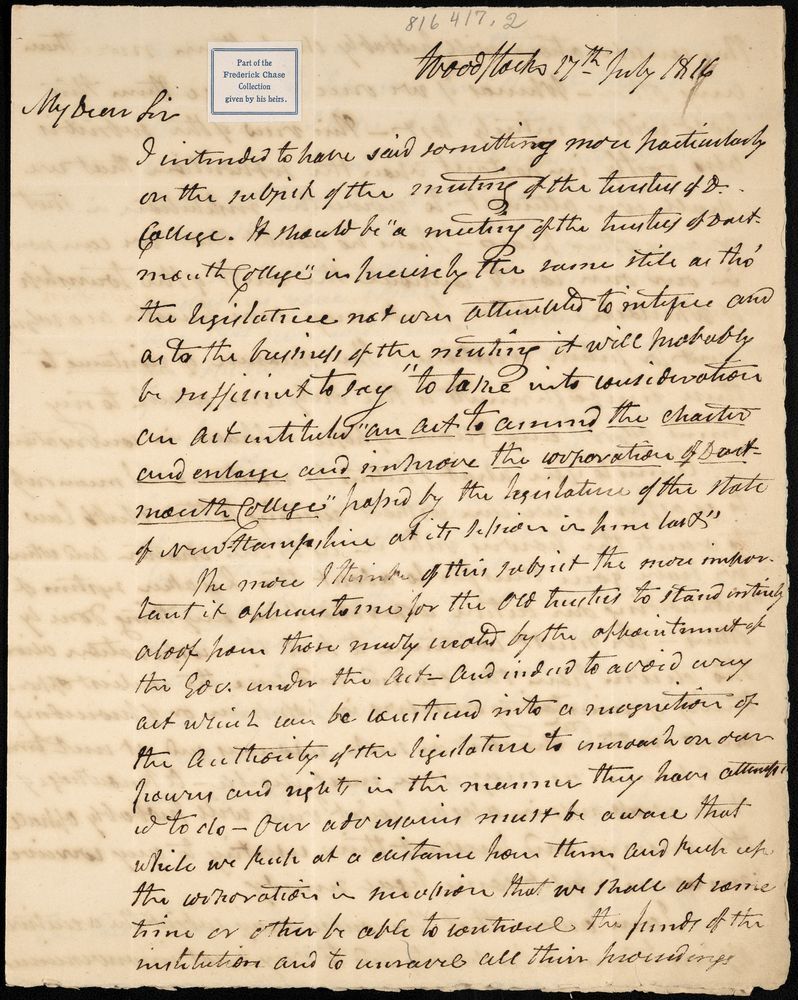

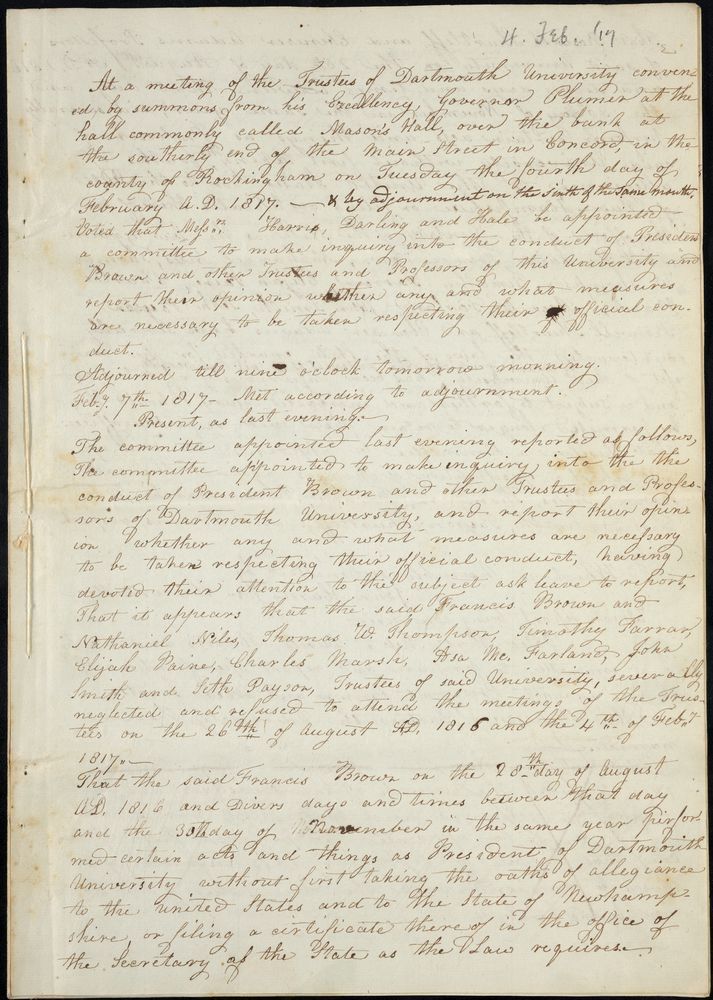

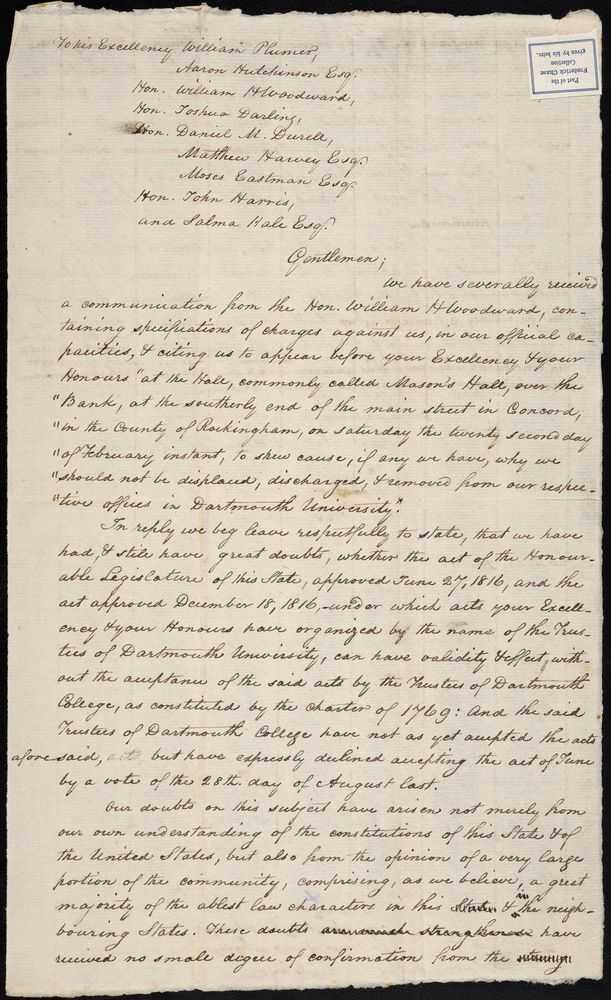

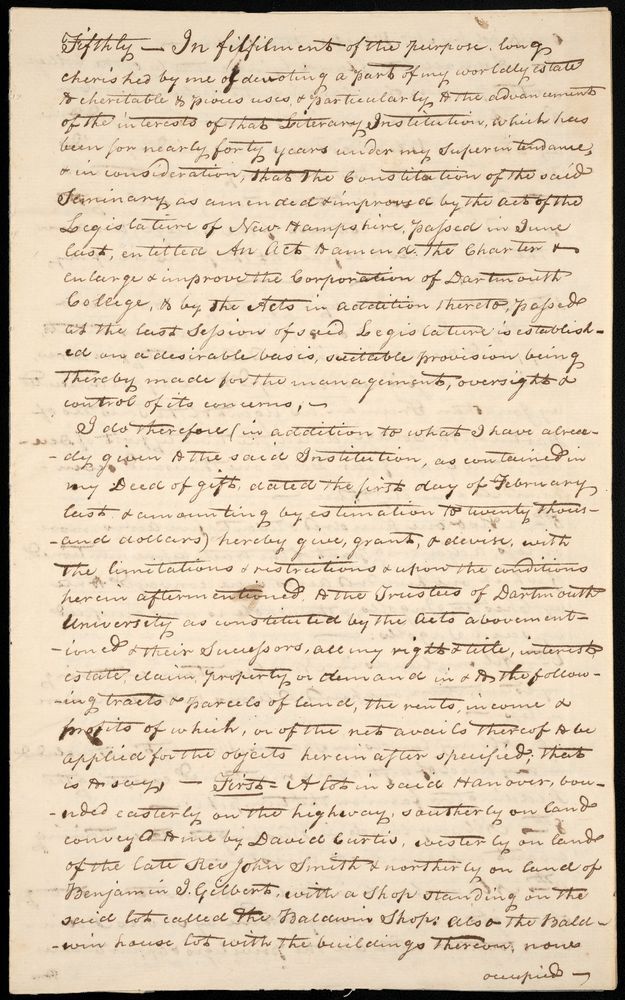

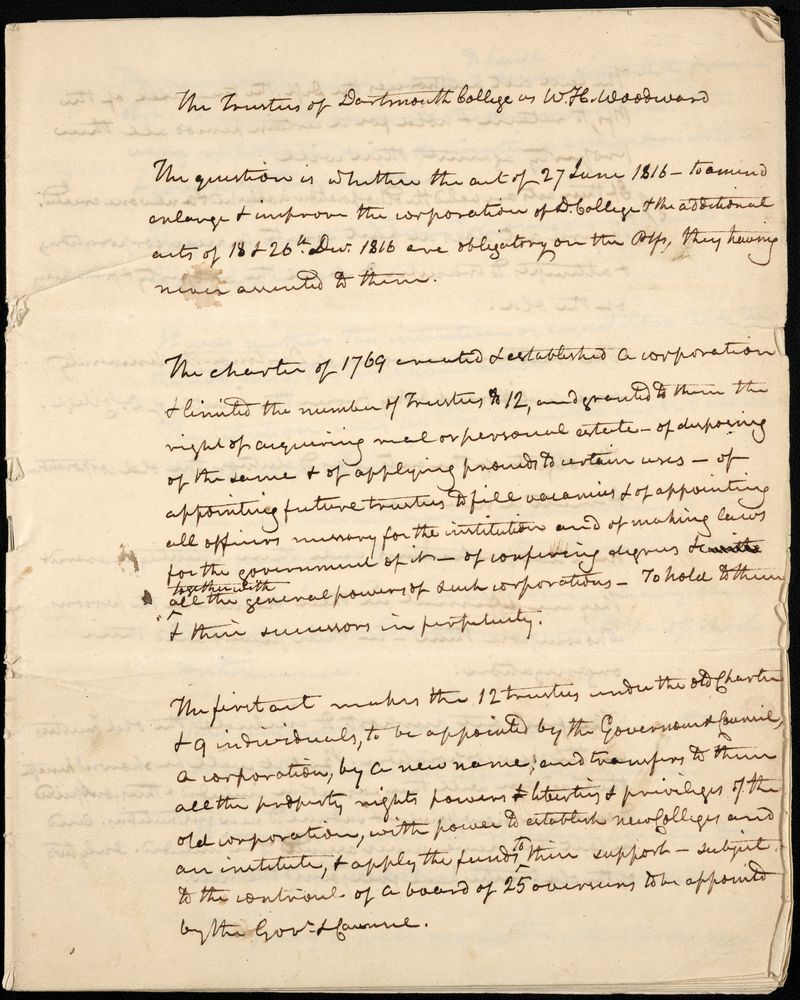

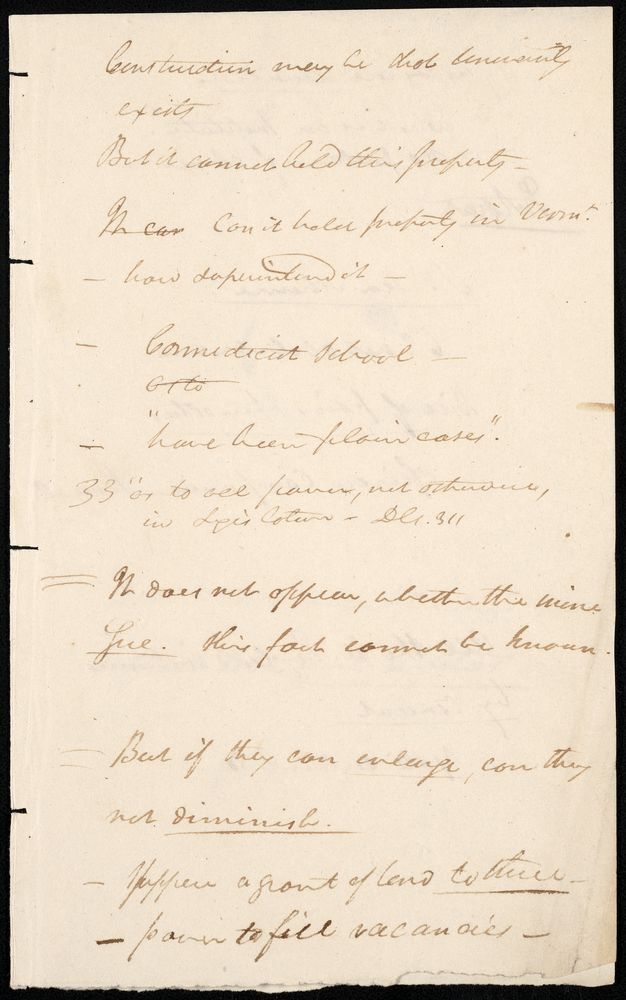

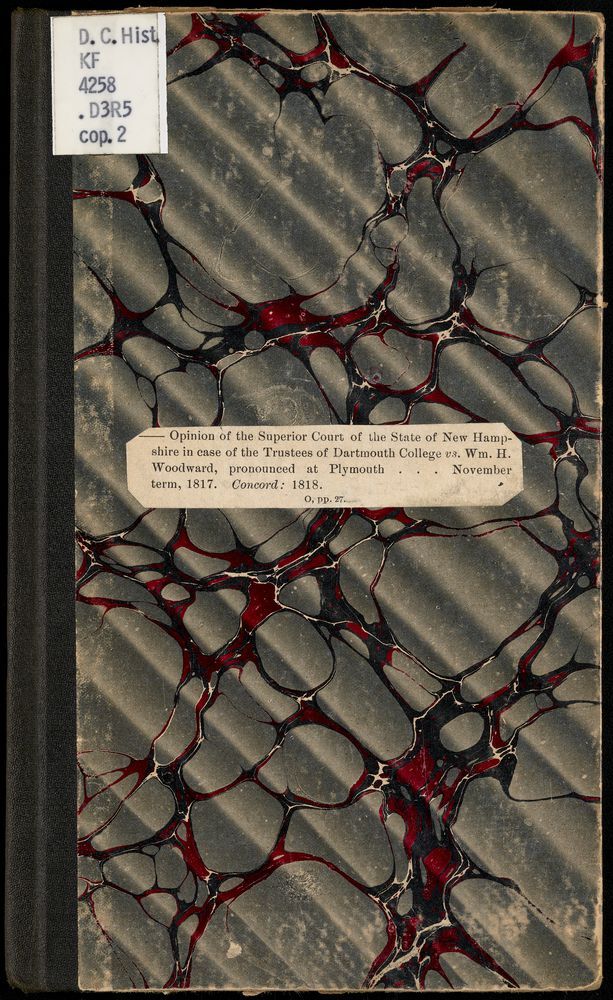

At the end of January 1817, the Trustees sued William Woodward (Secretary of the Board) to recover documents he had in his possession, including the finances and the Charter, when he defected to the University. The suit was initiated in the Court of Common Pleas for Grafton County on February 8, 1817, and was immediately transferred to the Superior Court of New Hampshire. In the midst of all this furor, John Wheelock died. The University Board appointed William Allen, Wheelock’s son-in-law, as University President. The College and the University quickly found themselves vying for the same legal counsel. The College ended up being represented by Jeremiah Mason and Jeremiah Smith, soon joined by Daniel Webster, Class of 1801. The University was represented by George Sullivan, the New Hampshire Attorney General, and Ichabod Bartlett, Class of 1808. Since the judges were all Republicans, appointed by Plumer, it was no surprise to anyone when the Court ruled for the State. The College’s counsel immediately began preparing a case to bring before the United States Supreme Court.

Previous: Dissent and Discord -- Next: Webster and the Supreme Court