Slavery During Dartmouth’s Founding and Early Years

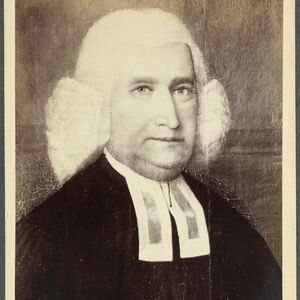

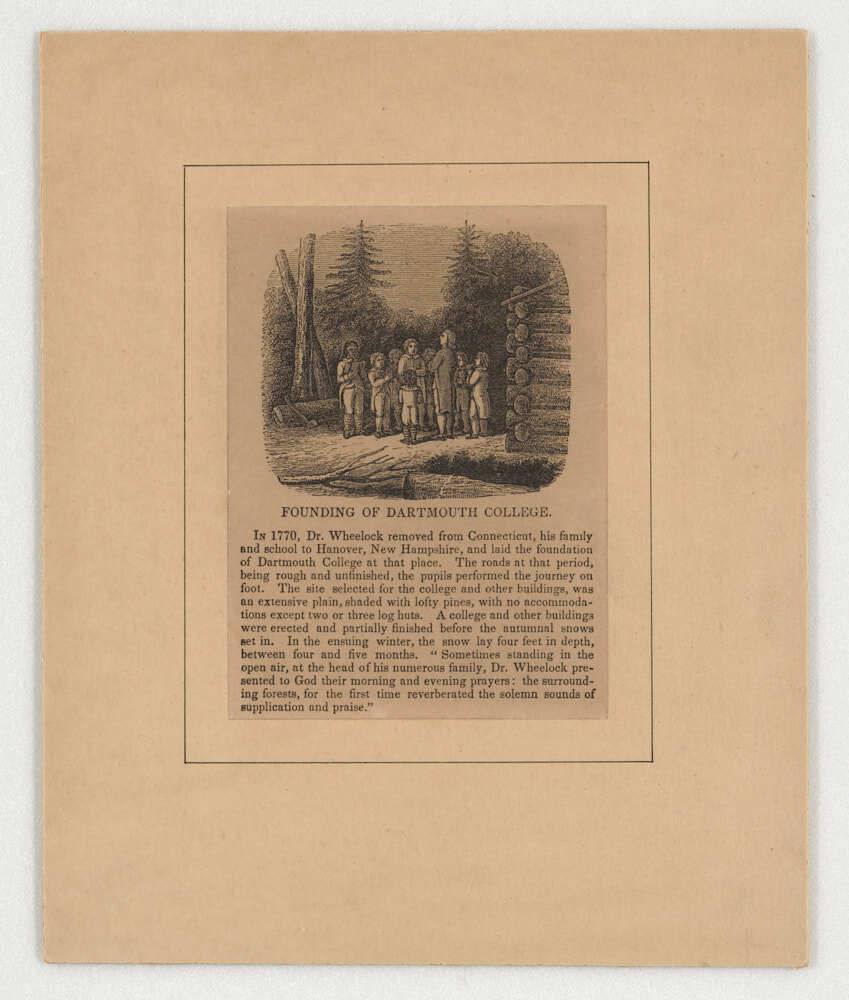

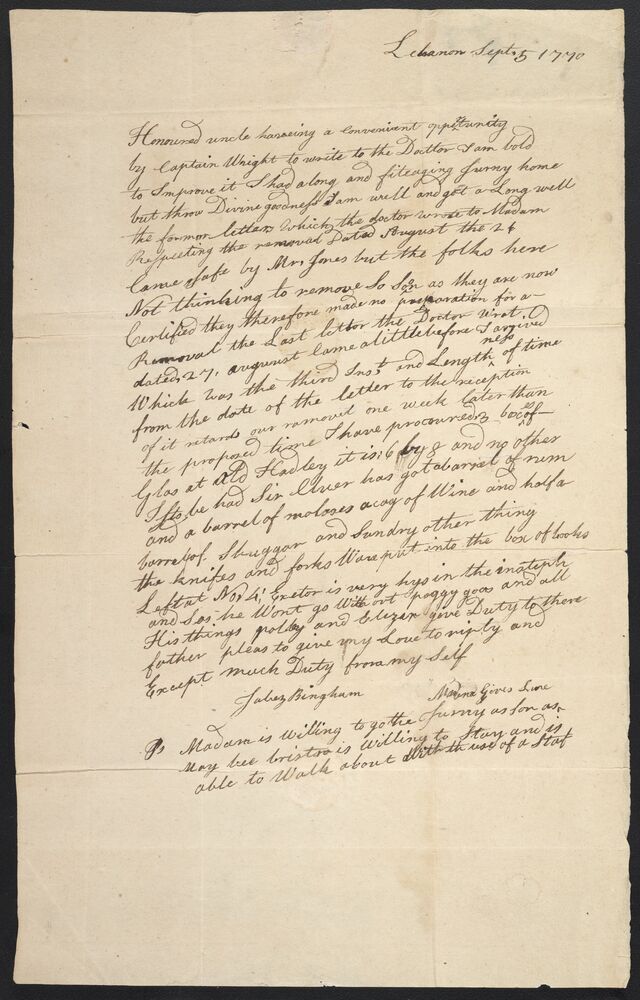

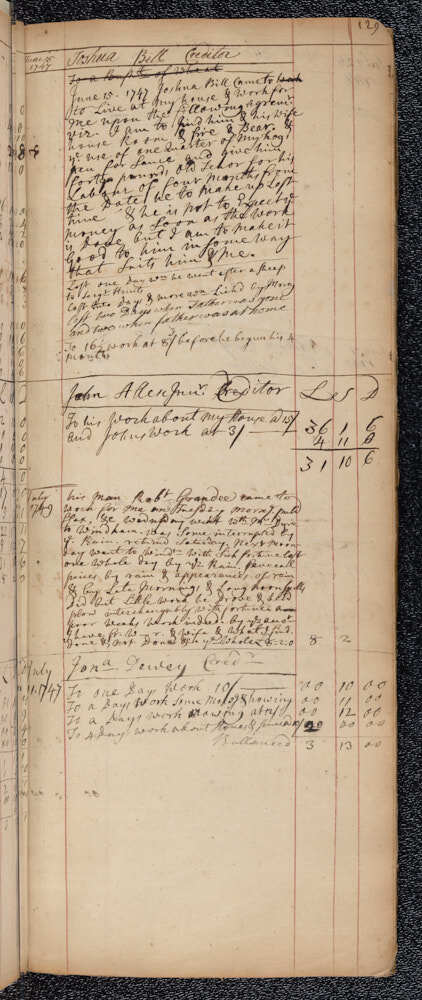

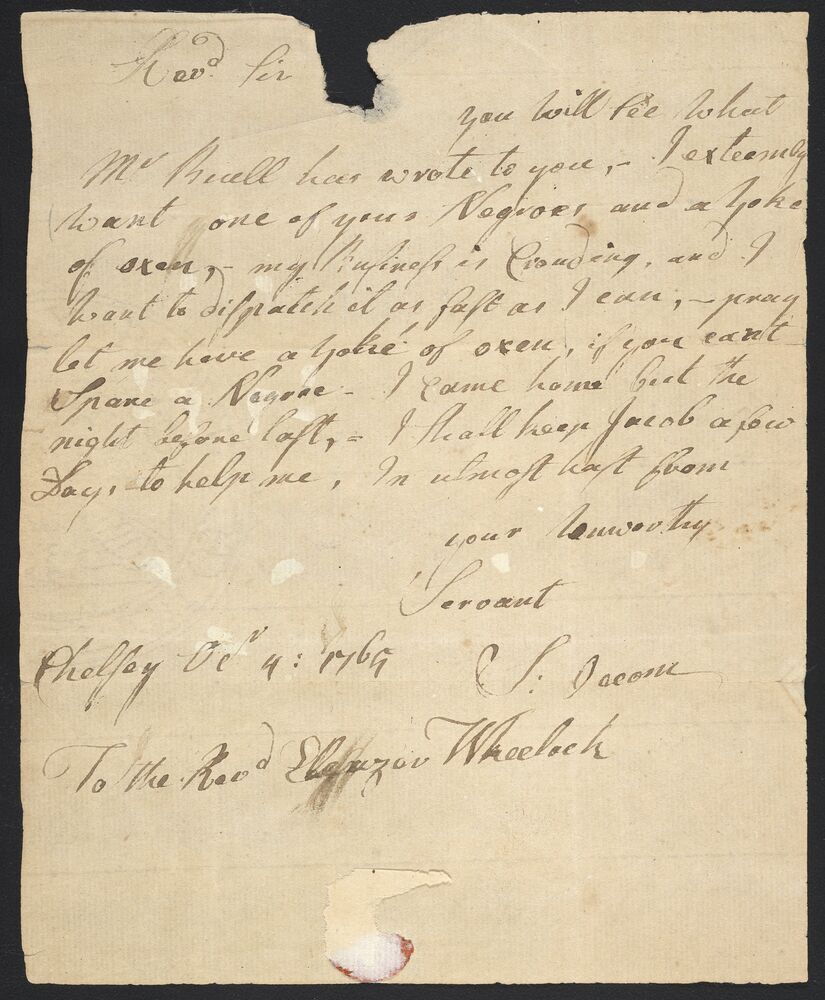

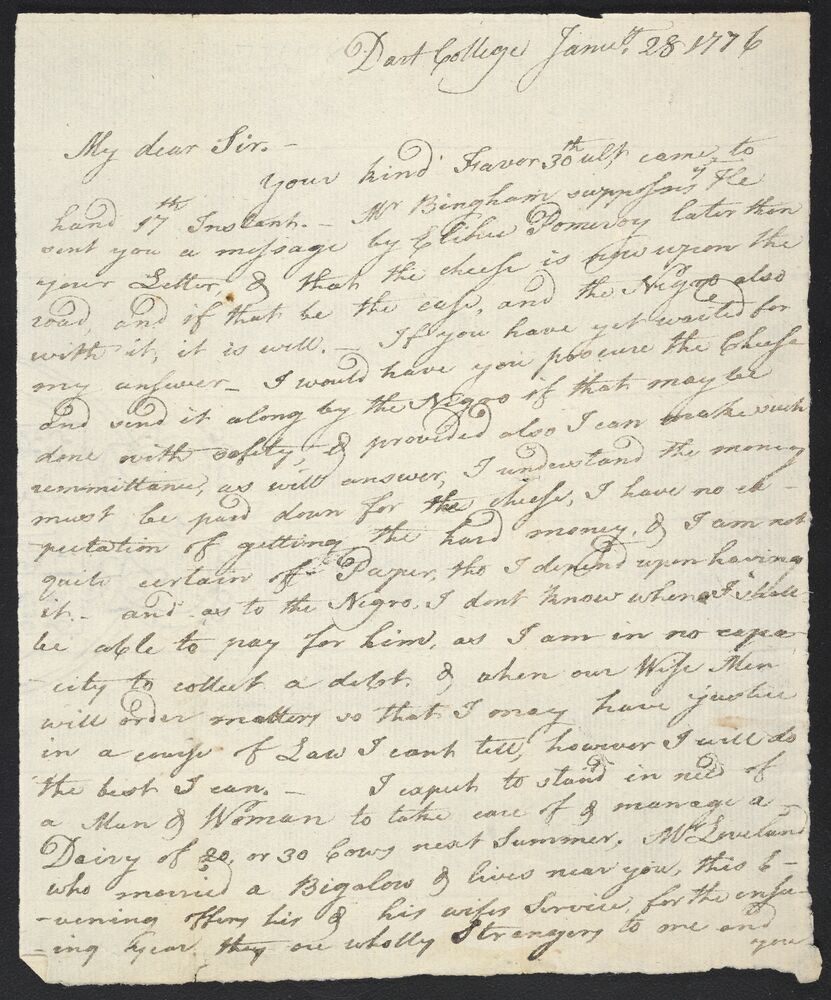

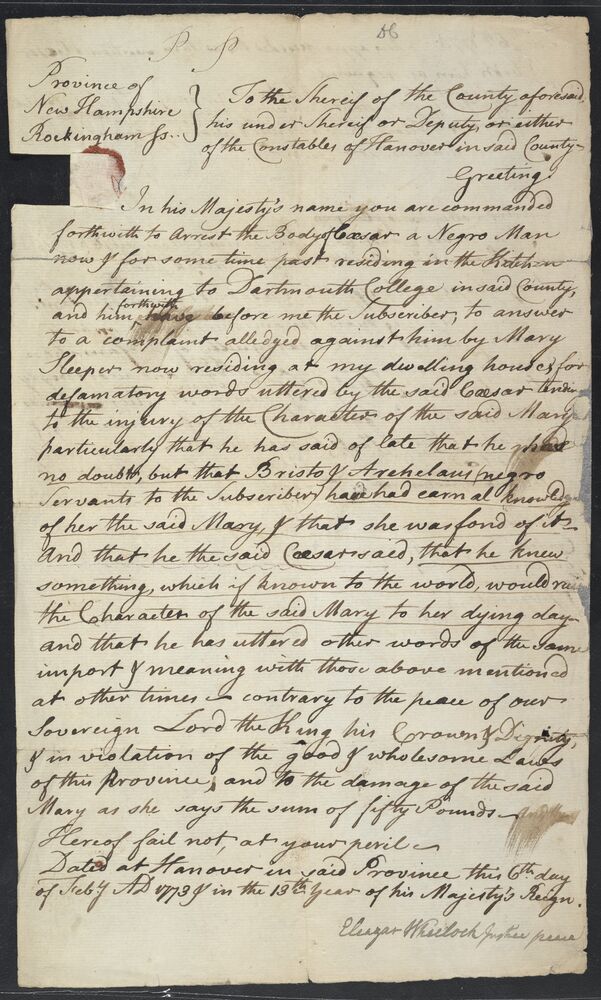

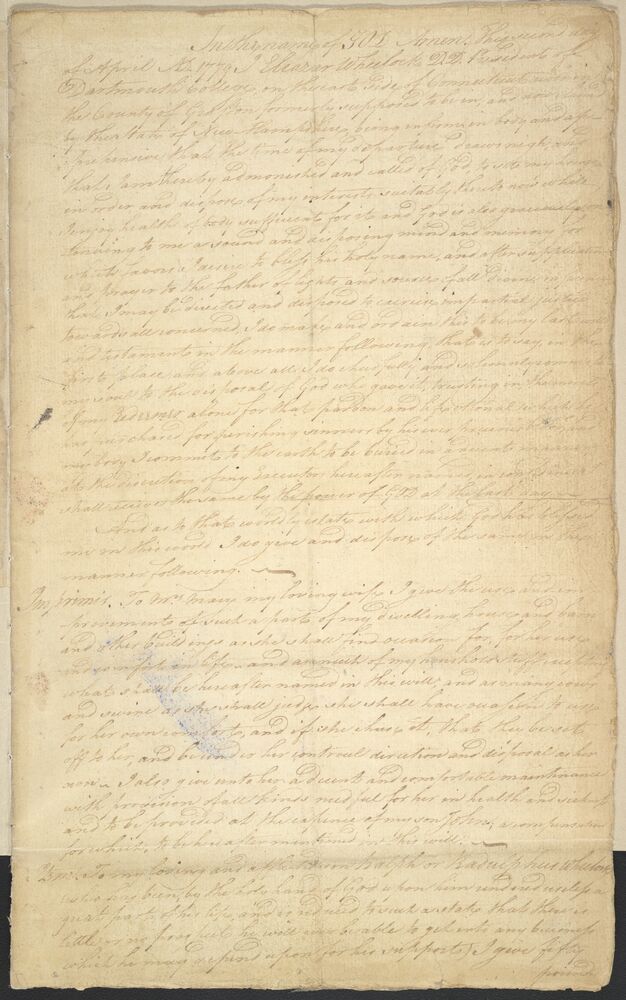

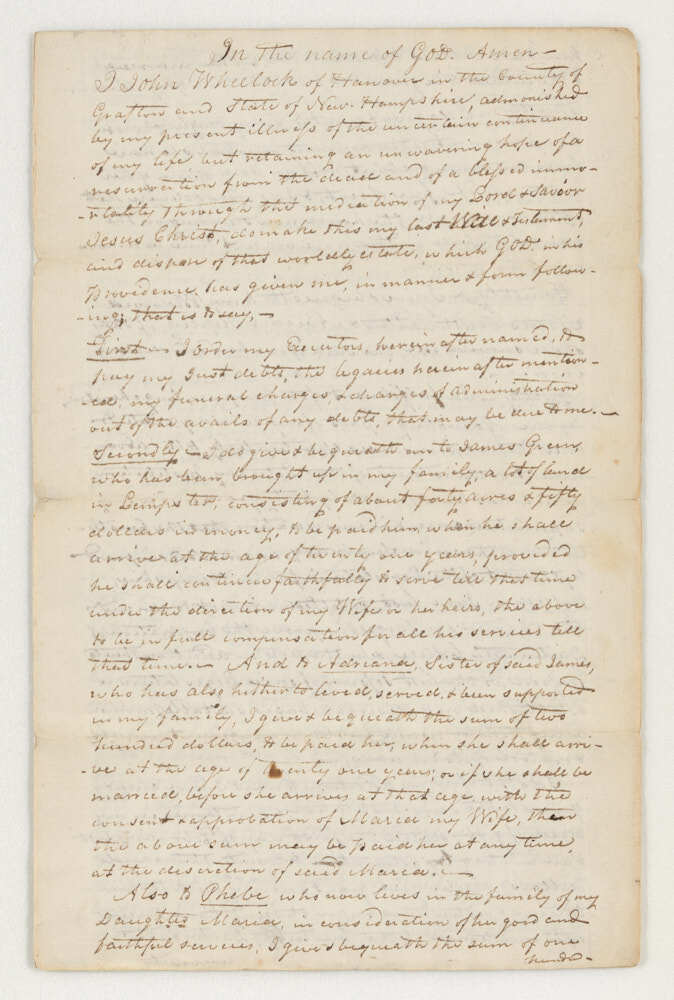

Stories of the founding of Dartmouth College often depict Eleazar Wheelock braving the wilderness as a pious pioneer of education. He had begun Christianizing indigenous people years earlier at the Moor’s Charity School in Connecticut, but he established the College in Hanover to educate “English youth and any others.” Dartmouth lore states that in August 1770, Wheelock arrived in New Hampshire with his students and several slaves. However, College Archivist Peter Carini has discovered that Wheelock owned at least nineteen enslaved persons during his lifetime. Their labors supported the well-being of President Wheelock’s family and his students and contributed to the maintenance of his home and the school’s buildings. Enslaved persons cleared trees, swept buildings, drove oxen, prepared meals, and cared for the sick. Enslaved as well as free people of color lived and worked in other Hanover households and businesses. In the historical records, we see glimpses of their loyalty to family members, their religious devotion, and their personal flaws. Slavery and the enslaved remained a part of campus life and in the North through the Civil War.

Previous: Home -- Next: Dartmouth and the Debates on Slavery