Learning Our History: Dartmouth, Asia, and America

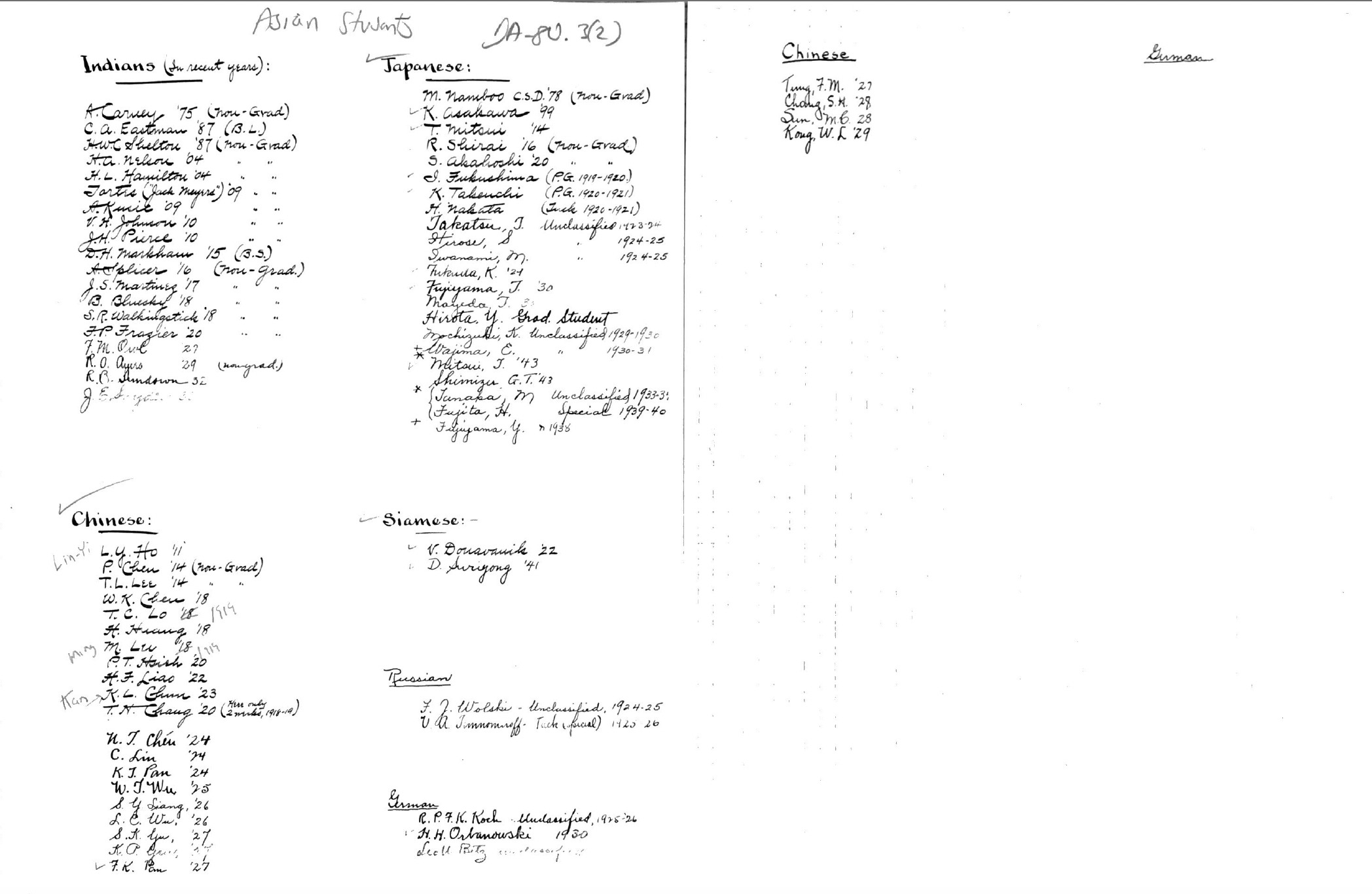

In the 1800s, the U.S. enacted immigration laws specifically barring various groups from entering the country. Consequently, Dartmouth had few students of Asian descent. Representation of different Asian ethnicities at Dartmouth is strongly tied to U.S. immigration laws that determine who is allowed in and who is not, setting up patterns for years to come.

Through the Civil Rights Movement, Dartmouth’s growing AANHPI community advocated for increased recognition and representation. It wasn’t until 1984 that Dartmouth included a self-identification category for admitted students of Asian or Pacific Islander descent. Today, 19% of the Class of 2027 identifies as Asian American.1

Though Dartmouth’s documentation remained inconsistent into the 20th century, students from the Asia Pacific region have been present since the late 1900s. Two white students, Charles Tenney, Class of 1878 and Homer Hulbert, Class of 1884, were significant allies to Asians following their graduation. Tenney went to China as a missionary and ended up raising his children there.2 Hulbert became an early advocate for Korean independence after his missionary service there.3 Kan'ichi Asakawa, Class of 1899, from Nihonmatsu, Japan, is Dartmouth’s first recorded alumnus and first faculty member of Asian descent.

A Global Presence in Hanover

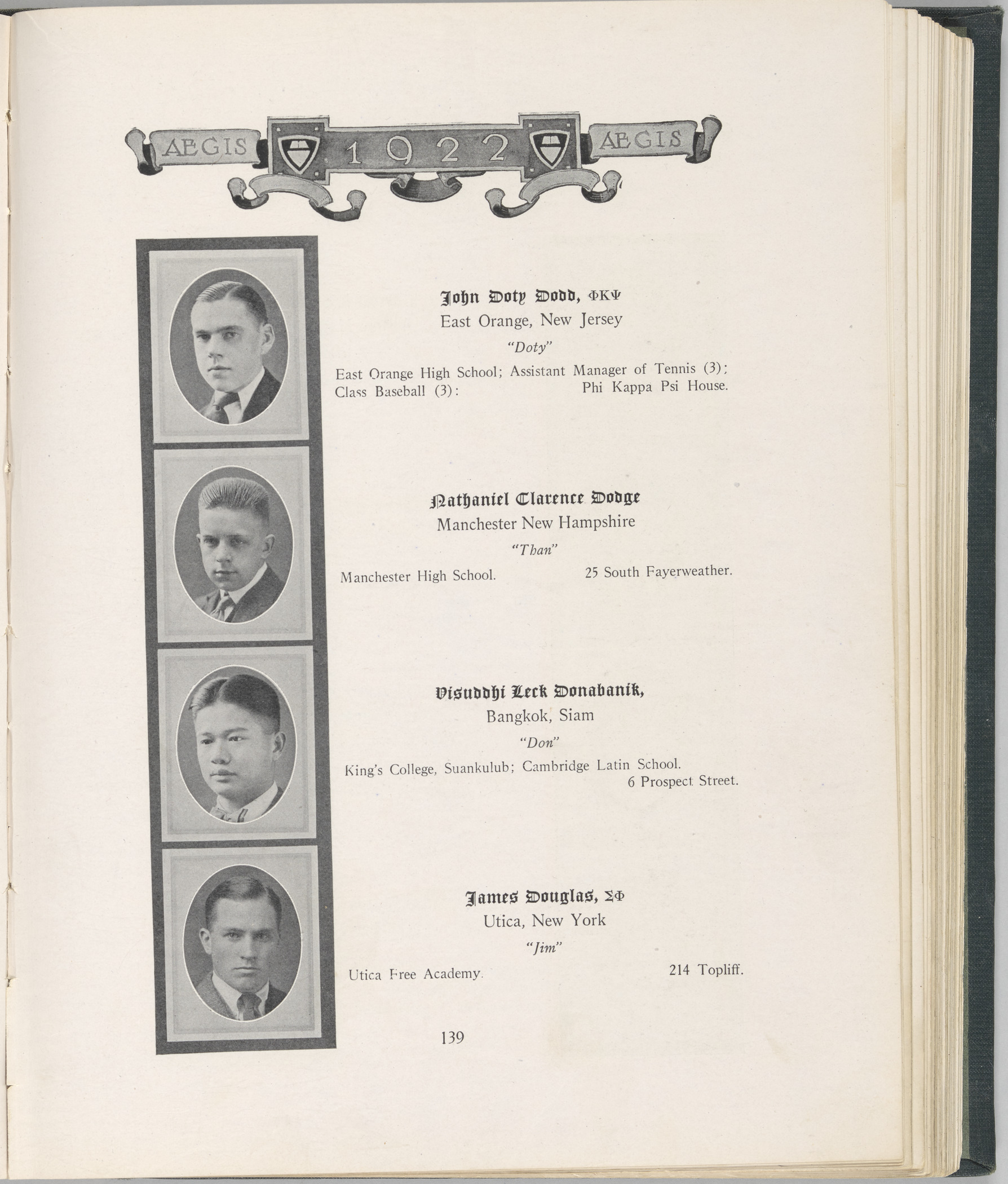

Against such a backdrop, Dartmouth became an unlikely site of intellectual exchange with the Asia Pacific region. Lin-Yi Ho, Class of 1907, an exchange student from Shanghai, China, reveled in the Dartmouth spirit, remarking that his “one wish is that the foreign element at Dartmouth will increase as the college grows, making Dartmouth a more cosmopolitan institution, whose influence may be felt at every corner of the earth.” 4

The next recorded student of Asian descent was Takanaga Mitsui, Class of 1915 P’43 P’58, a member of one of Japan’s most notable families. When he contracted acute appendicitis, the Japanese consul general, minister, and other diplomats arrived on campus to ensure that he was receiving the best care, which Dartmouth President Ernest Fox Nichols and his wife confirmed. Mitsui’s appendicitis was the start of international goodwill and diplomacy between the House of Mitsui and Dartmouth. Takanaga’s sons, Takanobu ’43 and Mamoru ’58, followed in their father's footsteps. Additionally, Mitsui & Co. sent nine students to study at the undergraduate school for a year, followed by another tradition of sending eight employees to study for one year at Tuck. With a $3 million dollar gift, Dartmouth created the Mitsui Endowed Professorship in Japanese studies.5

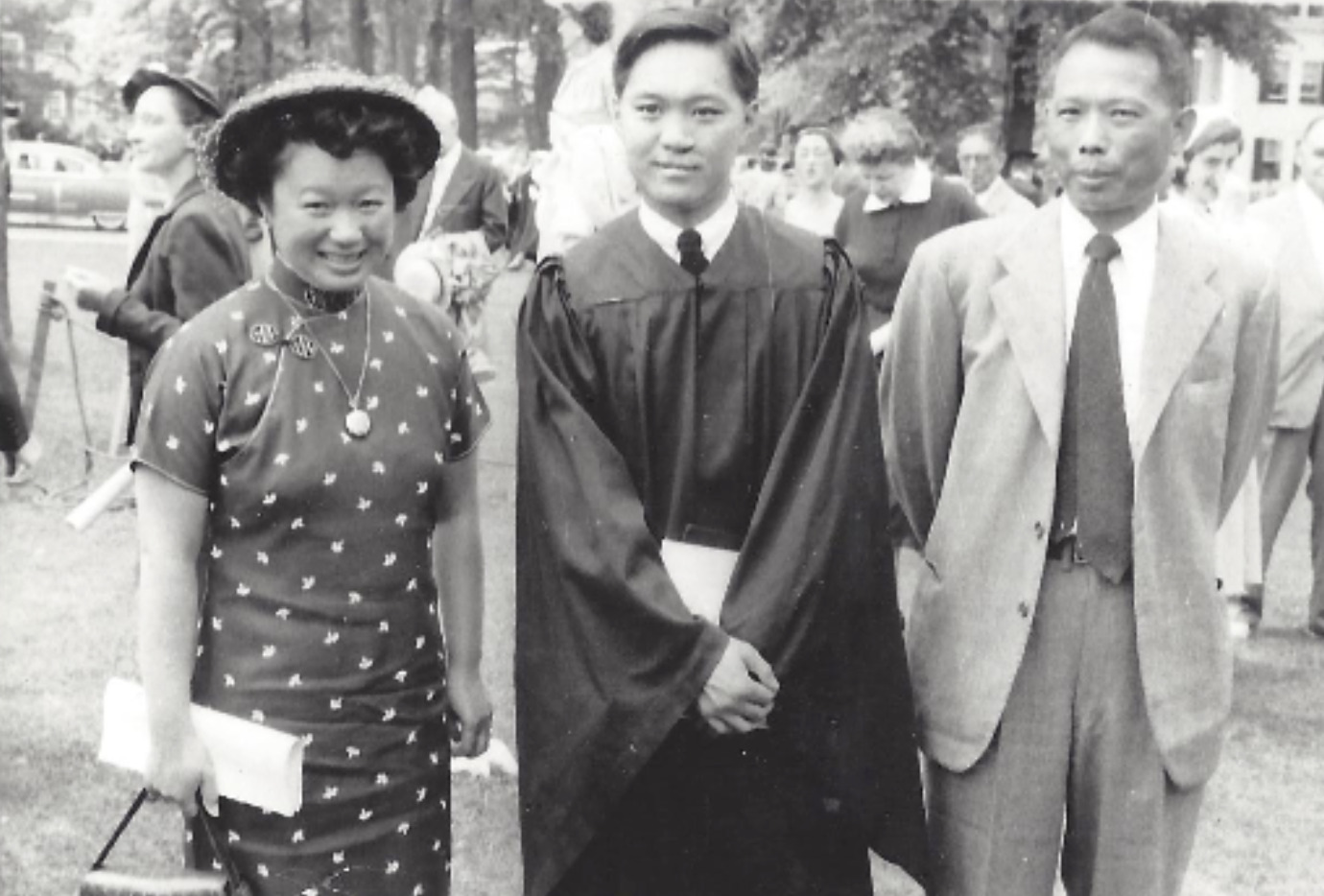

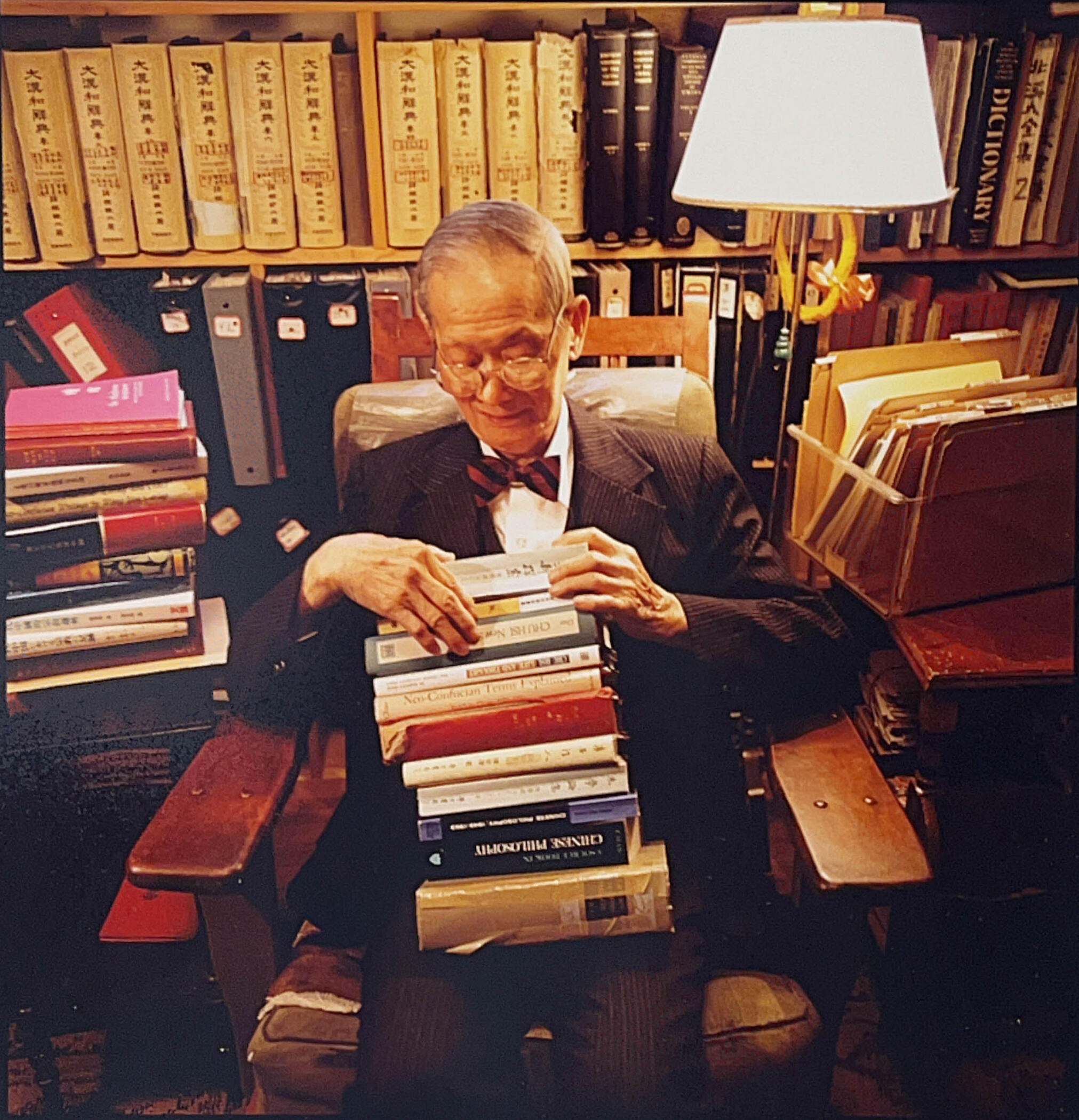

Dr. Wing Tsit Chan

Arriving in 1942, Chan was the first professor of Chinese heritage to accept a long-term faculty appointment at a U.S. university, retiring in 1966. He was also one of the first professors of Asian studies at Dartmouth. With a specialty in religion, philosophy, and Chinese culture, Chan helped introduce Chinese philosophy to the U.S. and developed the Asian Studies Program that continues today as the Department of Asian Societies, Cultures, and Languages. Chan, who taught until 1966, became one of the most respected and popular faculty members at Dartmouth during his time here. In a 2022 speech, President Emeritus James Wright described Chan as a teacher who “encouraged hundreds of other students to open their minds and hearts to different ideas and cultures.”6 In 1980, Dartmouth awarded Professor Chan with an honorary degree for his teaching and scholarship.

Profile: The progressive unity of history

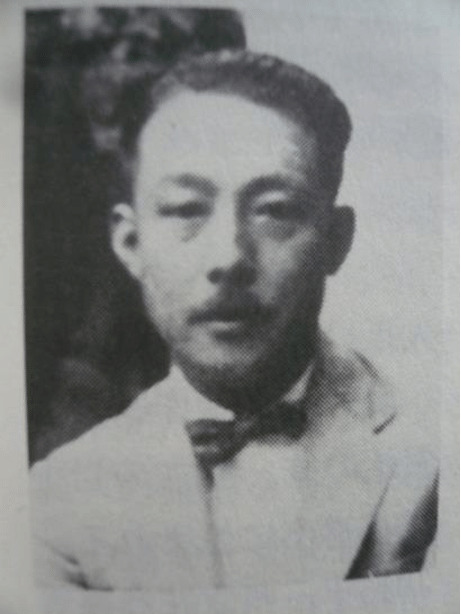

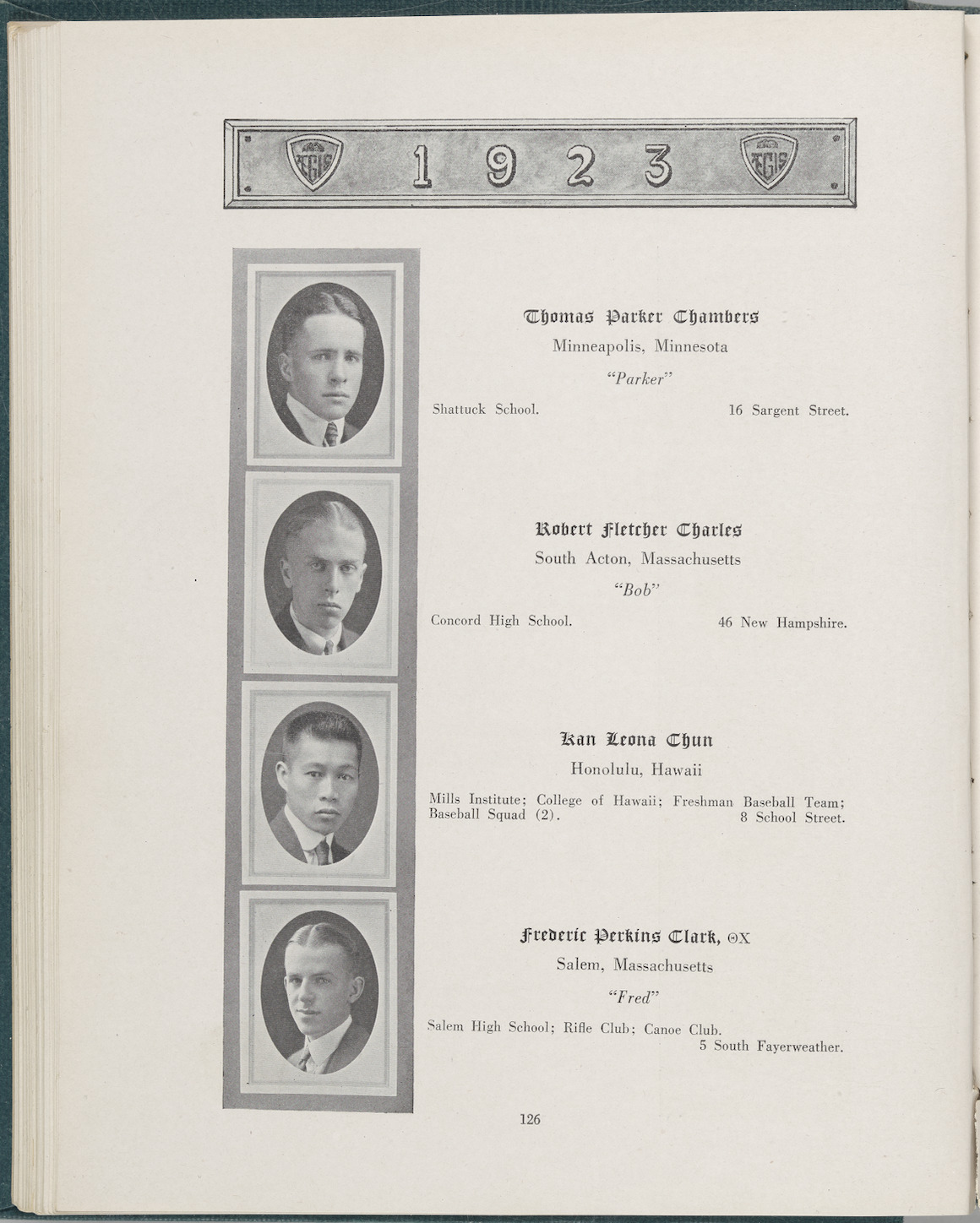

Kan'ichi Asakawa, Class of 1899

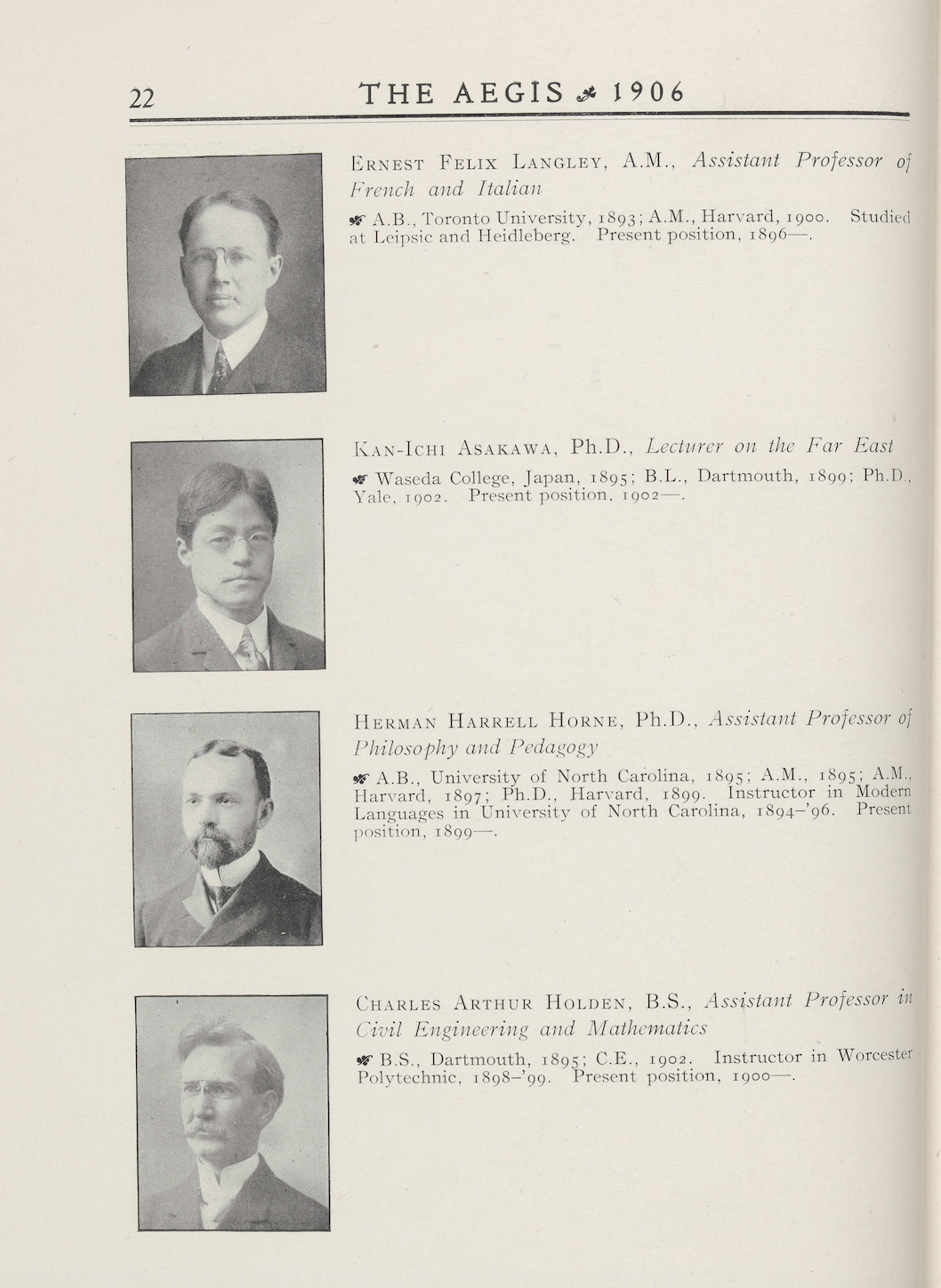

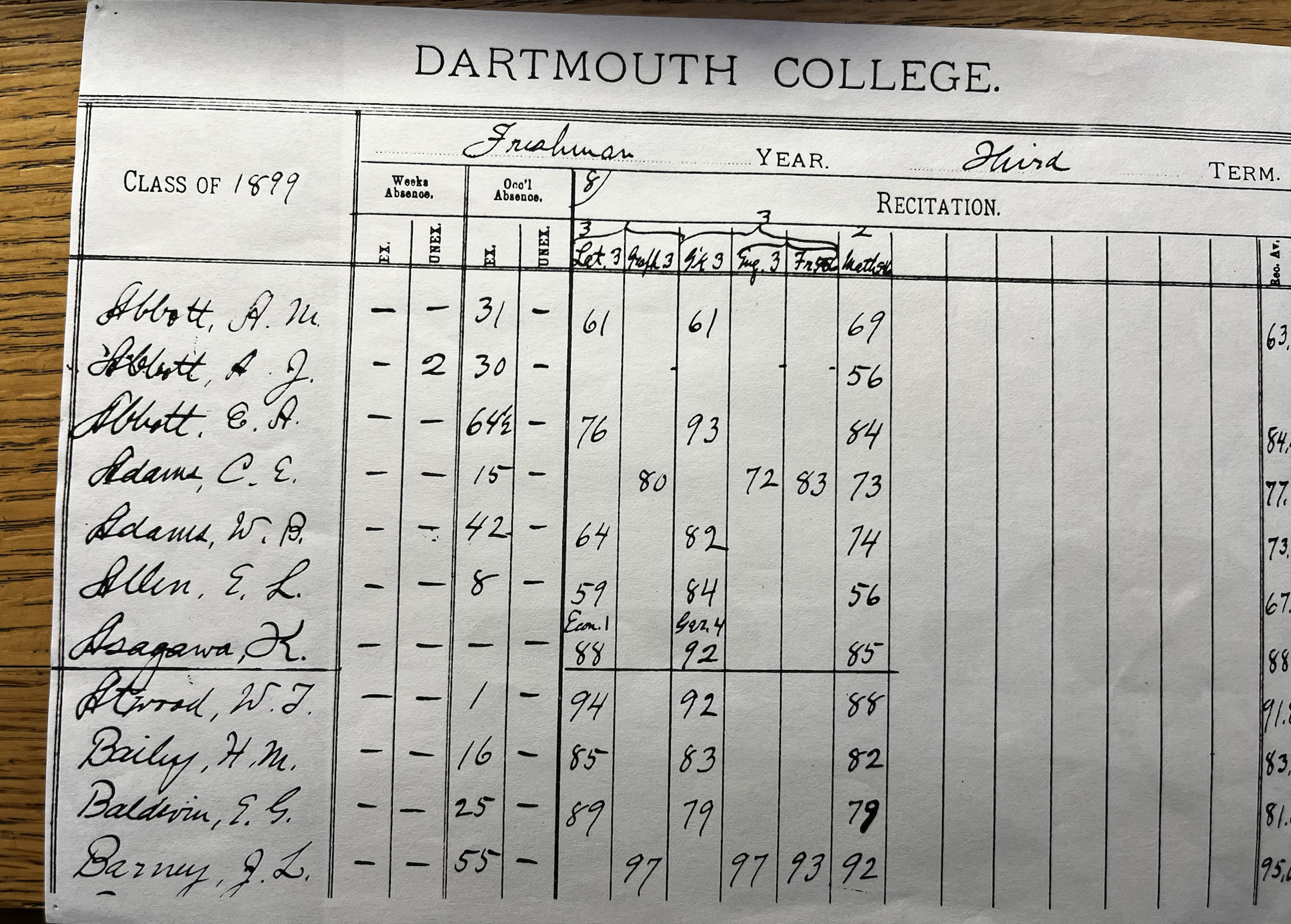

Born in 1873 to a lineage of samurai, Kan'ichi Asakawa, Class of 1899 gained notoriety for memorizing the entire English-Japanese dictionary before he stepped foot at Waseda University in Tokyo where he graduated in 1895. He is the first recorded alumnus of Asian heritage to graduate from Dartmouth College, as well as being the first faculty member of Asian heritage at Dartmouth, serving as a Lecturer on Far East Studies from 1902 to 1906.

Asakawa caught the eye of Dartmouth President, William J. Tucker who offered him a scholarship to attend Dartmouth. In a letter to Tucker upon his graduation, Asakawa spoke about his responsibility to “introduce my country in a better light than before to the wide intellectual world, to bring closer in understanding and sympathy the East and the West, and to further, however little, the progressive unity of history…a noble ideal worthy of aspiration.”

On Tucker’s urging, Asakawa pursued his PhD at Yale and taught at Dartmouth from 1902 to 1906, before returning to Yale in 1906. From 1906 to 1907, he taught at his other alma mater, Waseda University. In the meantime, his father had arranged a marriage for him in Japan and was surprised to find out that Asakawa was already married to a Euroamerican, dressmaker Miriam Dingwall, in 1905. Asakawa’s father approved of the marriage with the condition that the two have a traditional Japanese marriage ceremony, which they honored.

Life was not equitable for Asakawa. It took him 30 years before he became a full professor. As a U.S. resident for 52 years with Japanese citizenship. Asakawa noted, “I am neither here nor there. I am…an indigestible lump in any community.” Committed to the “imperative of truth” and mutual understanding, he dedicated his life’s work to scholarly research, focused on the infant science of sociology, investigating the rise and fall of feudalism in Japan and Europe, and growing concern of fascism in China and Germany. He sat next to President Theodore Roosevelt at the signing of the Treaty of Portsmouth, which is housed at Rauner, ending the Russo-Japanese War.

Dartmouth presented him with a Doctor Emeritus in 1931. Heralded as a renowned scholar, he maintained a relatively low profile and was known for his modesty, generosity, and unflagging devotion to scholarship until his death in Vermont in 1948. In his lifetime, Asakawa acquired tens of thousands of books and materials, mostly housed at Yale and the U.S. Library of Congress. Today, Dartmouth students studying abroad in Japan make a pilgrimage to the town of his birth, Nihonmatsu and his high school. The Dartmouth Club of Japan has honored his legacy with the Kan’ichi Asakawa Award on nine separate occasions to those who “exemplif[y] the spirit of international understanding [and] provide inspiration to all those who endeavor to construct and cross bridges of finer communication between people of different cultures.”

(1) Dartmouth undergraduate admissions class profile; Note: After the 2023 SCOTUS decision on affirmative action, we expect reporting to be different and adherent to a new process. We're waiting to see how this plays out.

(3) Dartmouth Libraries Rauner exhibit: "When Two Worlds Meet" by Hannah Chung