Ahead of her time and fearless explorer

After centuries of illustration solely for medicinal interest, botanical illustration in the 17th century was thriving with Dutch florals, garden culture, and Pteromania (fern mania), leading to the Golden Era of Botanical Illustration (1750-1850). Detailed botanical illustrations that captured several different features of the plants were becoming more useful to the early taxonomists. In Europe, there was interest in standardizing the classification of plants to allow for meaningful international collaboration and transfer of information.

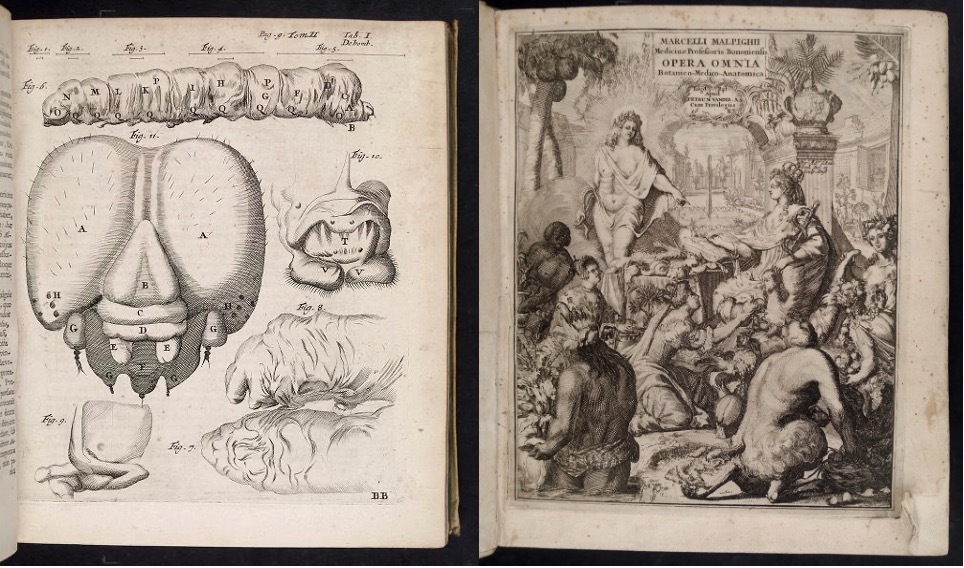

Records show that there were only a handful of female botanical artists in the 17th century, but Maria was by far the most prolific and the most dedicated to the observation and illustration of live specimens. Maria preferred observing whole organisms undergoing changes, unlike other contemporary naturalists of the day, like Robert Hooke and Marcello Malpigh, who were dissecting and magnifying to focus on microstructures. Maria was interested in observing and telling a more complete story.

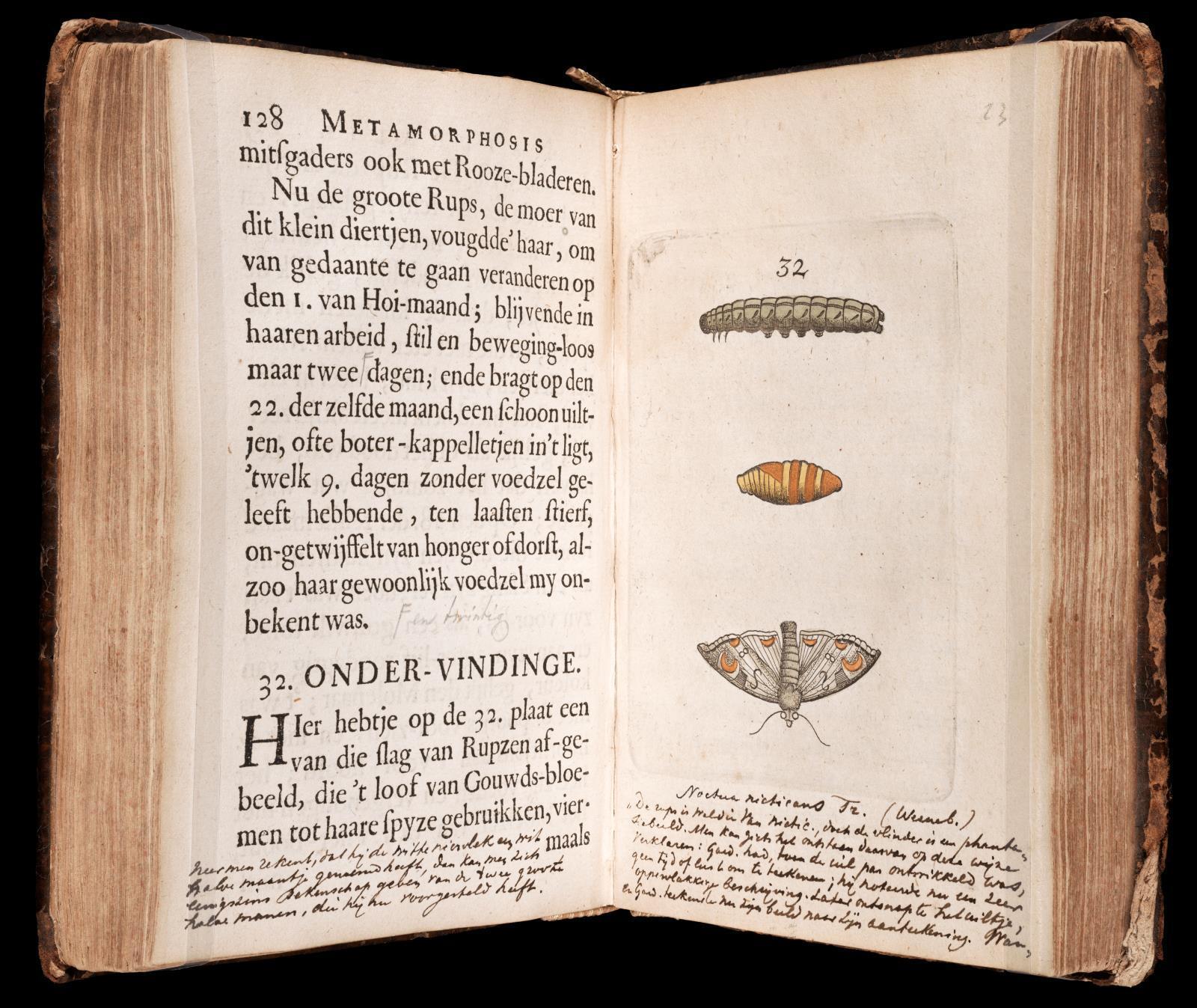

The 1662 book Naturalis Metamorphosis by Johannes Goedart, one of the first books to discuss metamorphosis beyond the idea of spontaneous evolution of insects, was an inspiration to Maria’s work. Goedart’s style of direct observation became the basis for all of Maria’s work. Her determination to capture the full story is reflected in the 12 years it took for her to successfully raise a caterpillar to the adult moth Hyles euphorbiae as a model for her illustrations.

Maria also stands out because of her life circumstances: it was not common for women of her time to get divorced and then take off to study botany in South America with their children. Several illustrations that she created during her trip were the first-ever representations of the species.

Three plates from Johannes Goedart's Naturalis Metamorphosis

Johannes Goedart, Naturalis Metamorphosis, 1662. The plate on the right-hand side shows moth species with three life history stages. Goedart used etchings instead of woodcuts.

(Source: MFA Boston Digital Collection.)