Past, present, and future of field observations

Field documentation is an important skill set for scientists across various disciplines. There is no substitute for careful observation and documentation during field trips. Even in today’s world of digital note taking and cell phone photography, there is a need for simple hand drawn notes that capture details and ideas that slip the lens.

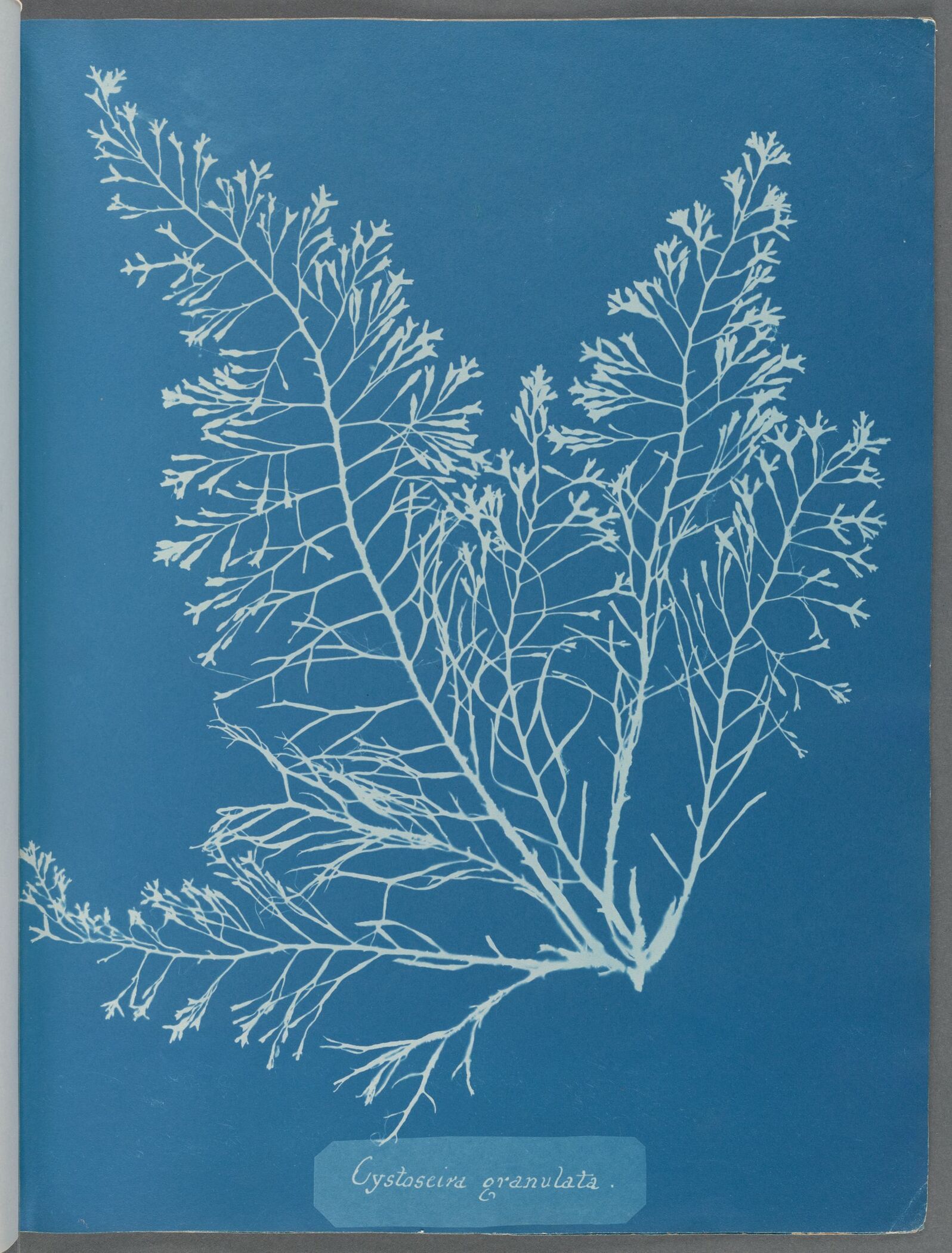

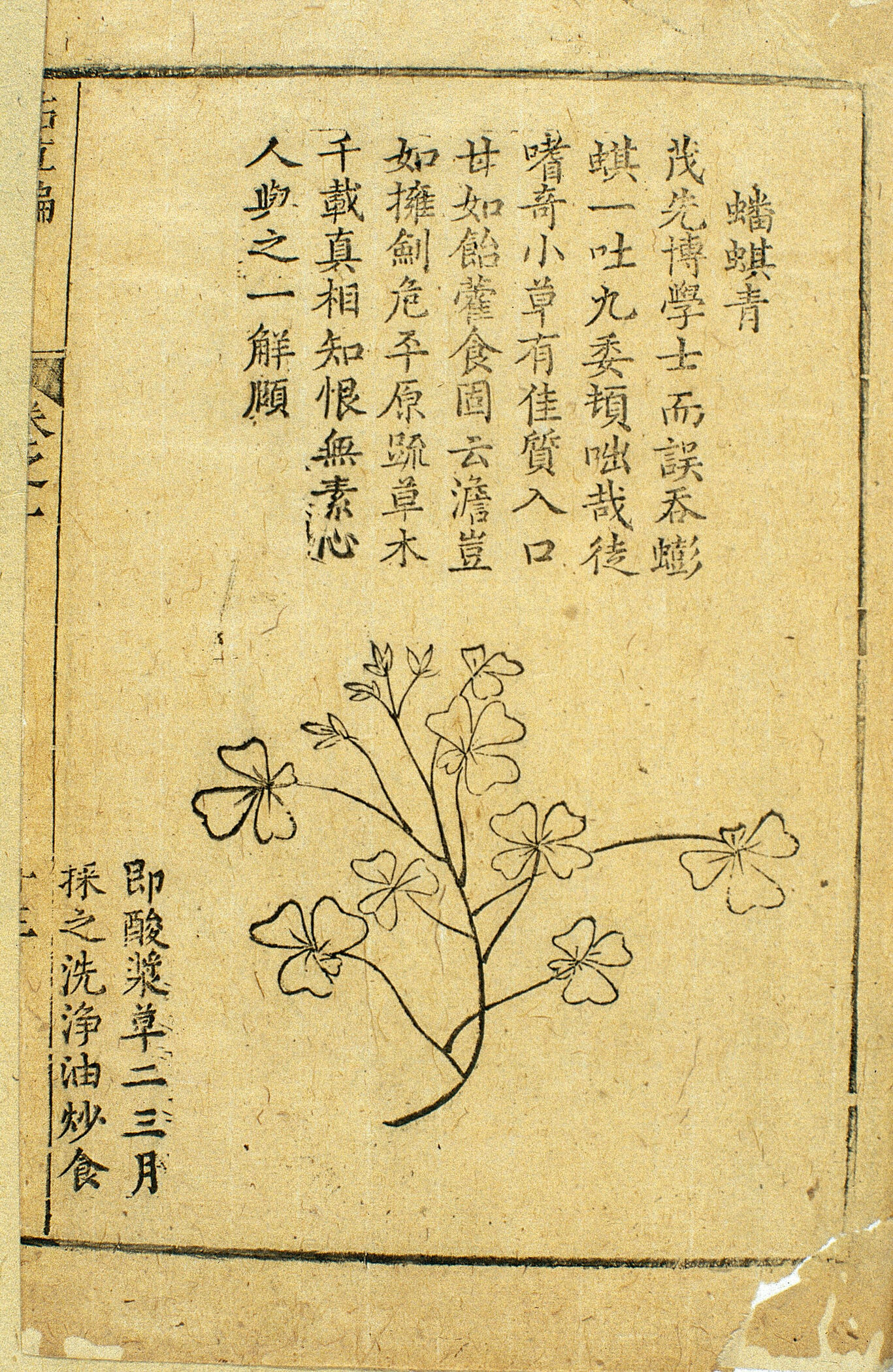

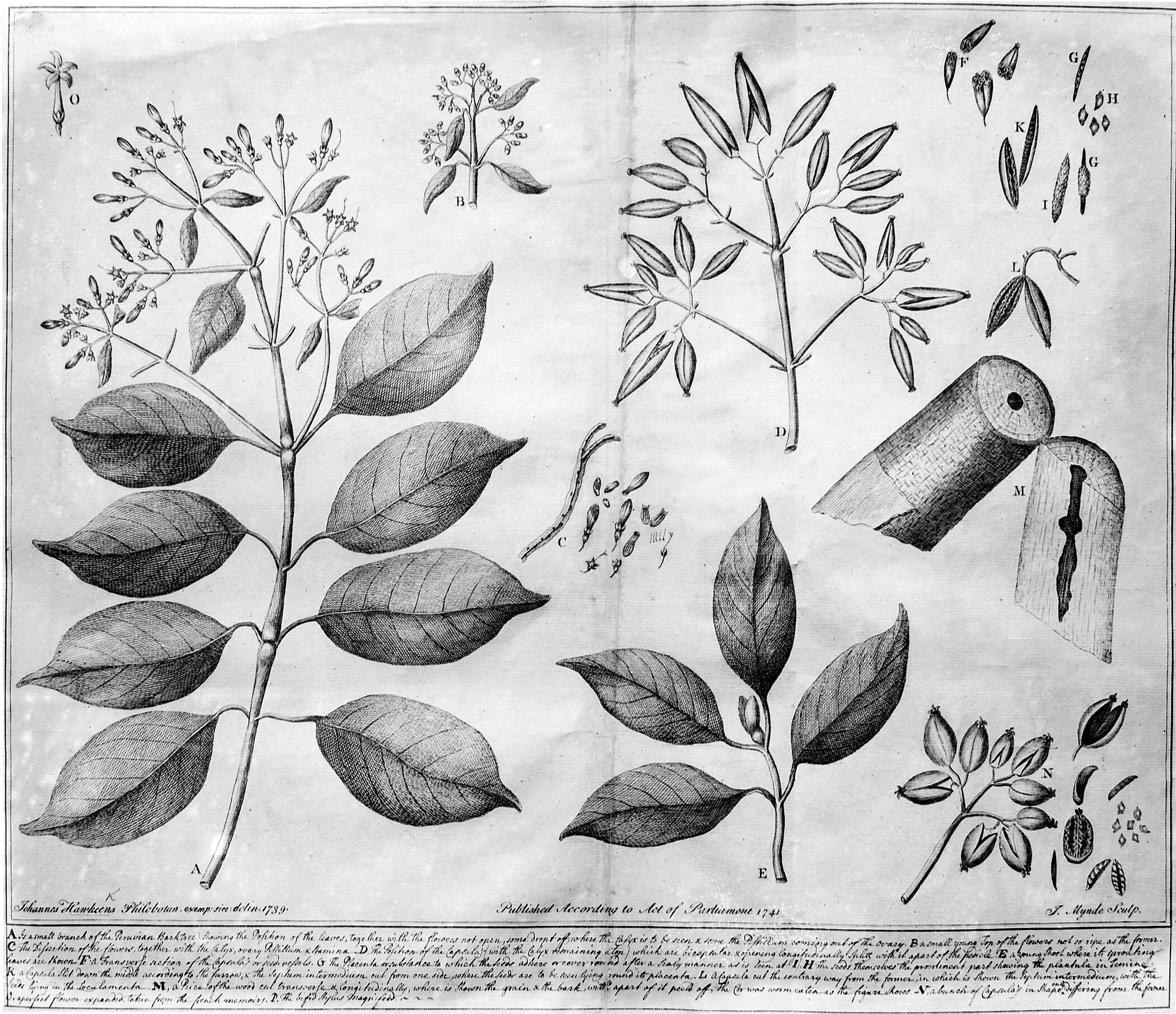

Field notes offer historical insights for researchers and help capture long-term observations, helping scientists recognize patterns beyond those found in quantitative data. From early woodcuts used in herbals to more detailed botanical illustrations, field observations have supported the accurate replication of identifying characteristics of various plant groups. Copper engravings and etching followed by printing were the earliest ways that illustrations could be copied for mass production.

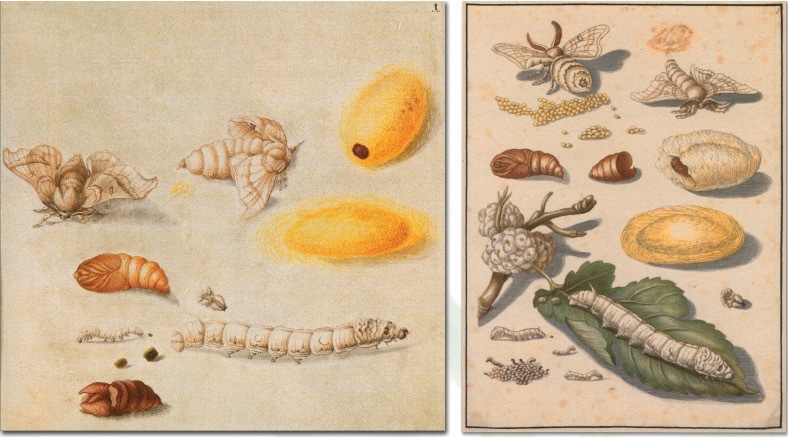

Maria developed a specific numbering system in the 1660s to connect her research notes to her paintings and vellum sketches. The incomplete dates in several instances indicate the interruptions she experienced while working on natural history observations, due to limited access to specimens at the necessary stages. Maria is also known to have combined observations of similar species. It is always a challenge to know how detailed field notes need to be, so it is important to dig into the literature of a discipline to learn the norms.

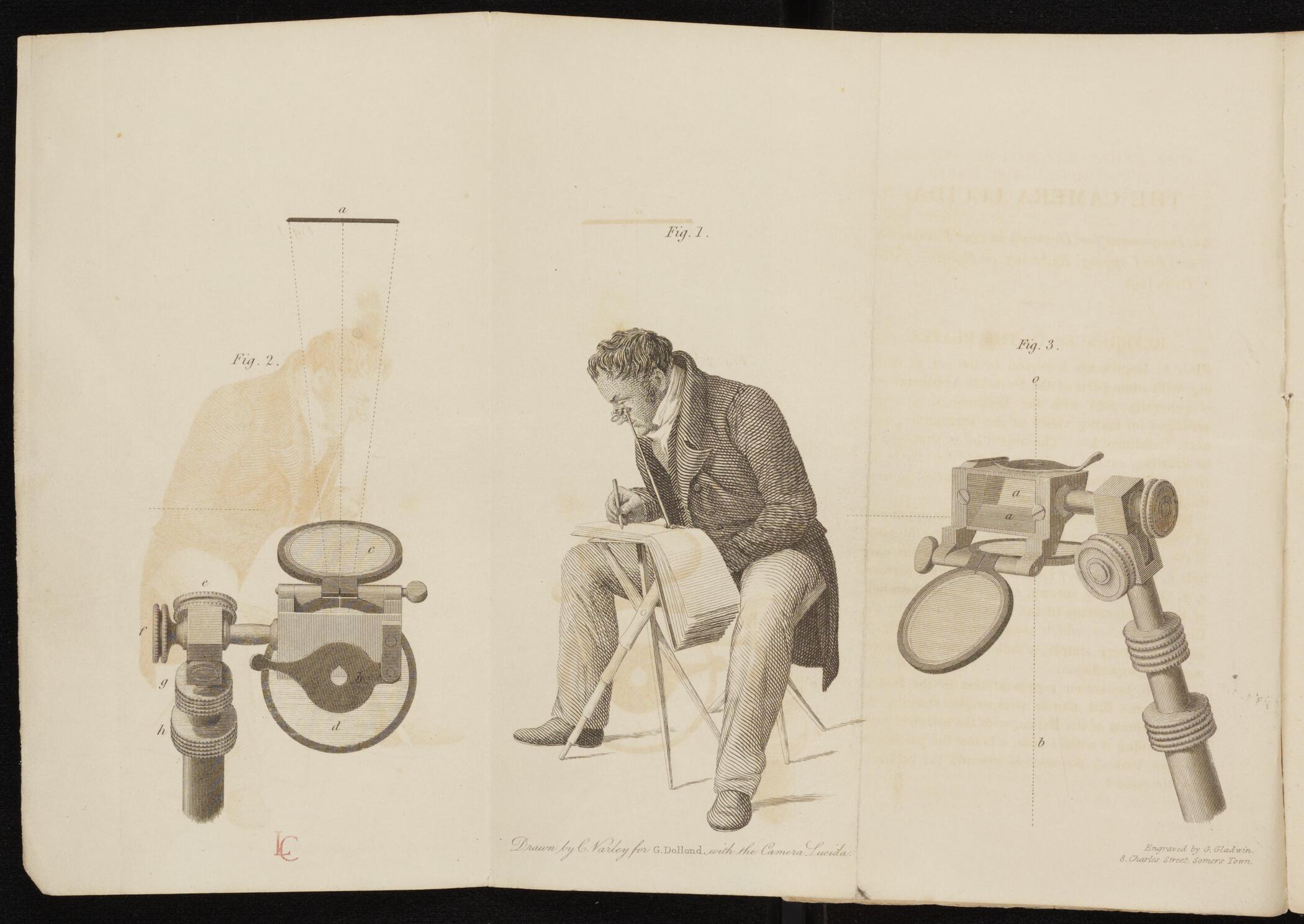

The invention of the camera lucida in the 18th century allowed illustrators to become more accurate without losing speed. The camera led to a slump in the popularity of watercolor and copper engraved illustrations; however, there was a resurgence of botanical and natural illustrations beginning in the 1950s. The American Society for Botanical Artists (ASBA) and the Guild of Natural Science Illustrators (GNSI) are two contemporary organizations that offer classes and mentorship for budding natural history illustrators.