-

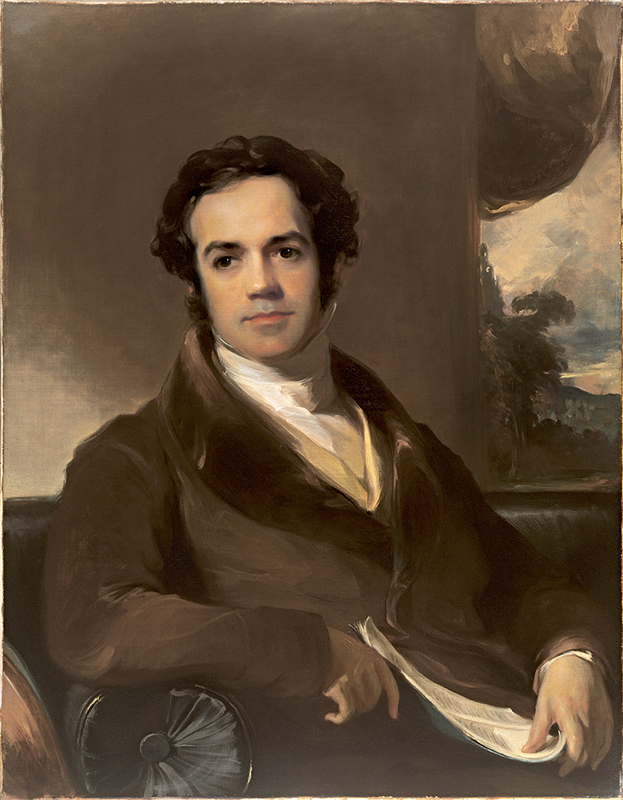

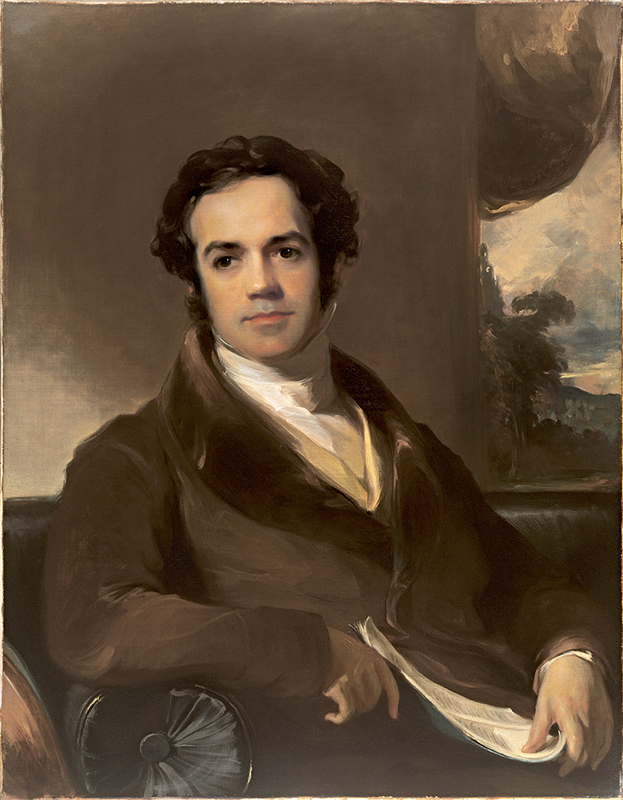

Thomas Sully, George Ticknor (1791 1871), Class of 1807, 1831, oil on canvas. Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth: Gift of Constance V.R. White, Nathaniel T. Dexter, Philip Dexter, and Mary Ann Streeter; P.943.130.

-

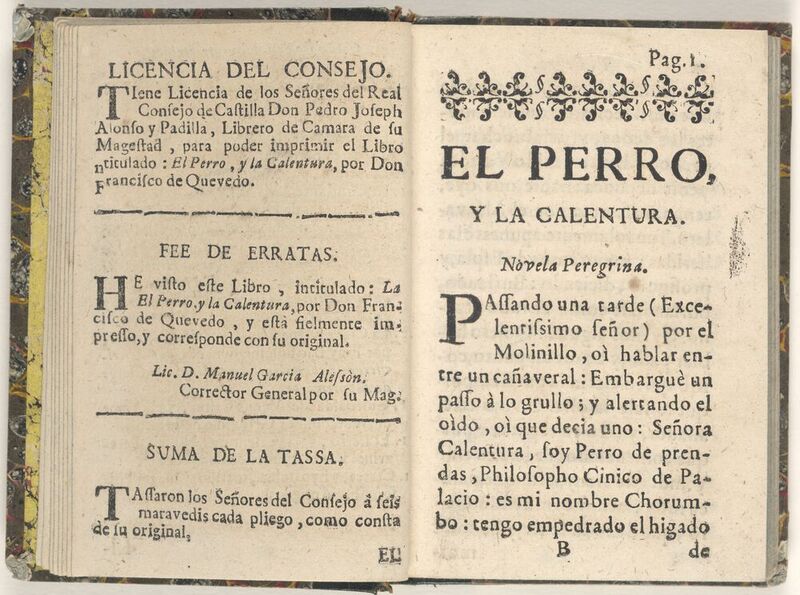

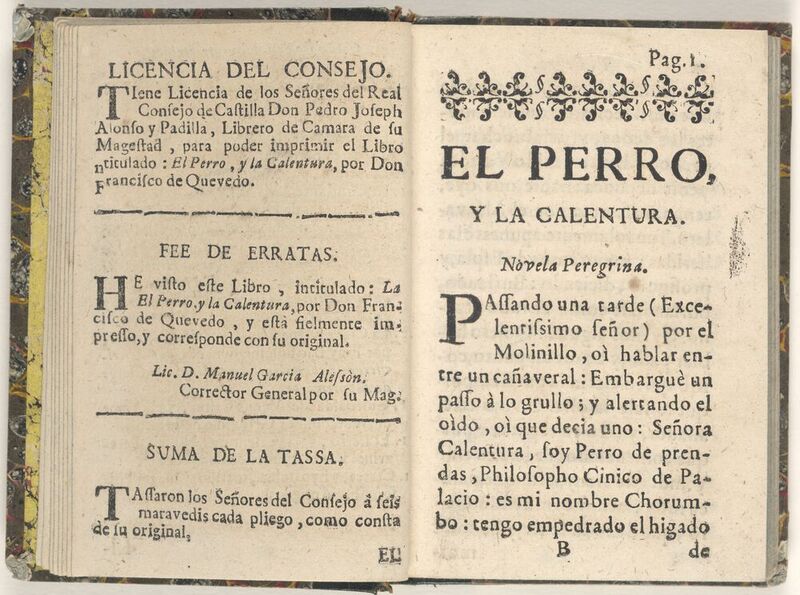

The leading Golden Age Spanish poet, Francisco de Quevedo, features prominently in Ticknor’s History of Spanish Literature.

-

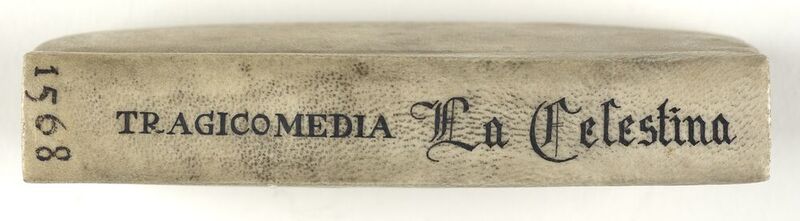

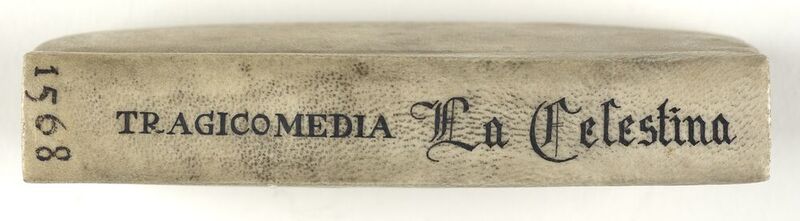

Ticknor includes a lengthy discussion of La Celestina, by Fernando de Rojas, in his History of Spanish Literature. Writing of one of the most important texts of the late medieval and early modern period, Ticknor’s analysis reveals the influence of his Boston Brahmin milieu: “The great offence of the Celestina, however, is, that large portions of it are foul with a shameless libertinism of thought and language. Why the authority of church and state did not at once interfere to prevent its circulation seems now hardly intelligible.”

-

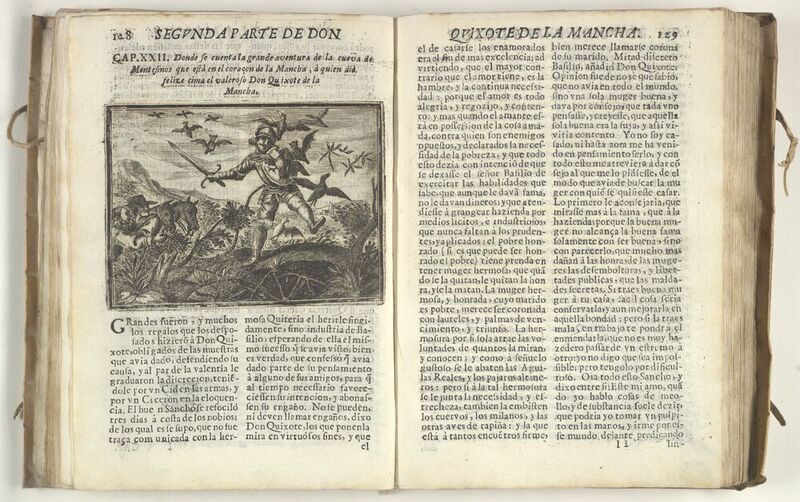

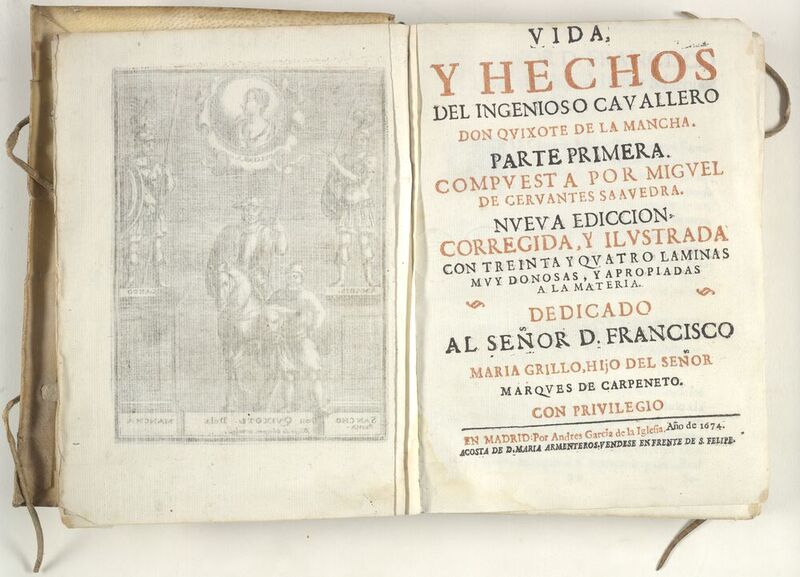

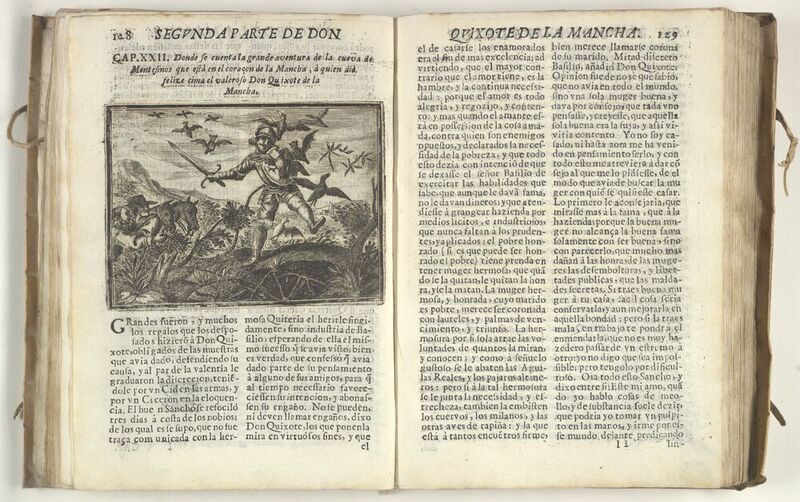

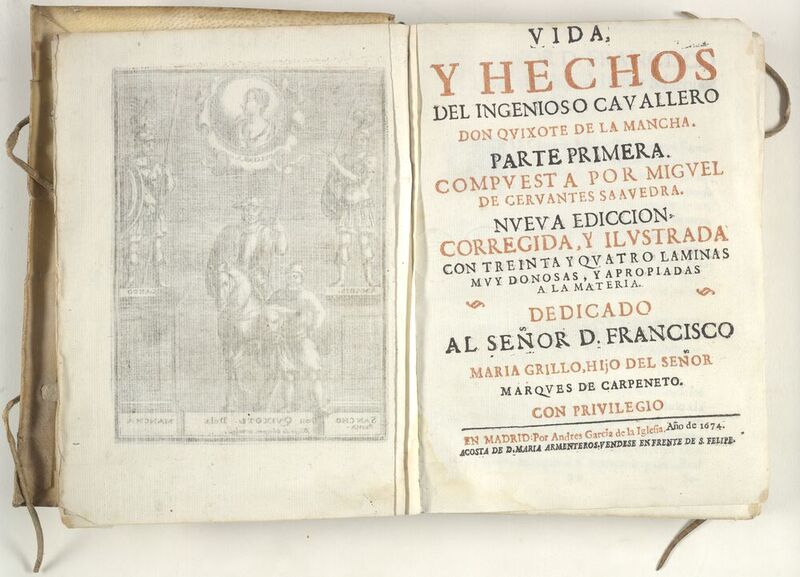

Engraving depicting Don Quixote’s descent into the Cave of Montesinos.

-

Ticknor reveres Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote. In his journal, he notes, “We slept at Alcalá de Henares, the Complutum of the Romans, the place where the famous Polyglot was printed, and, what is more to me than all this, the birthplace of Cervantes, the unimitated, the inimitable Cervantes.”

-

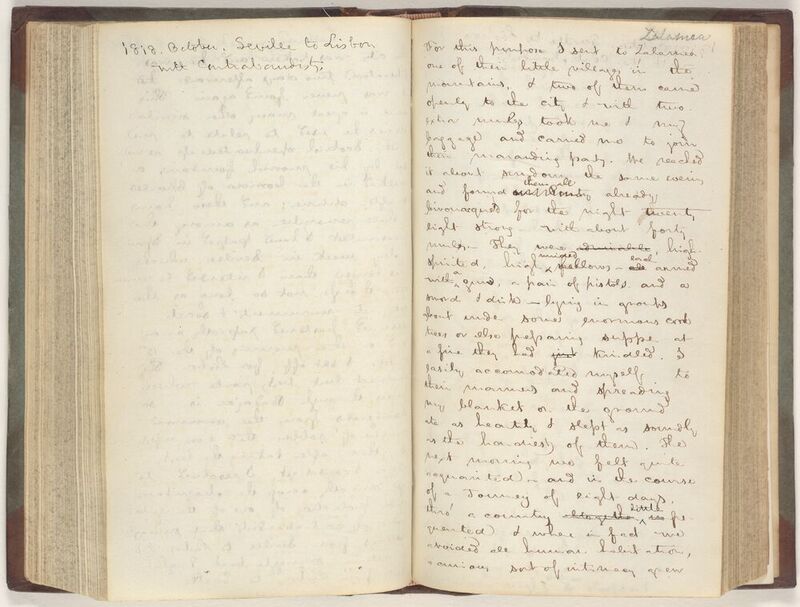

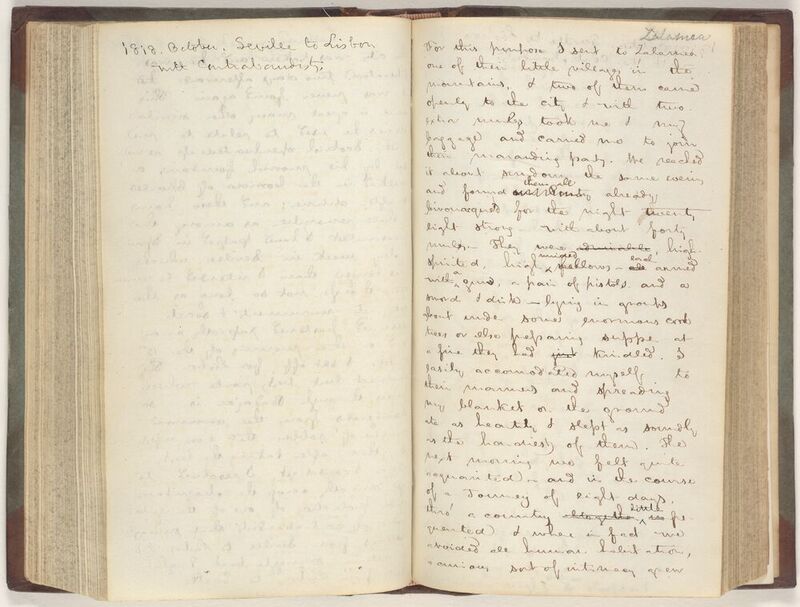

In this passage, Ticknor seems to relish what he describes as a dangerous journey with contrabandists from Seville to Lisbon.

-

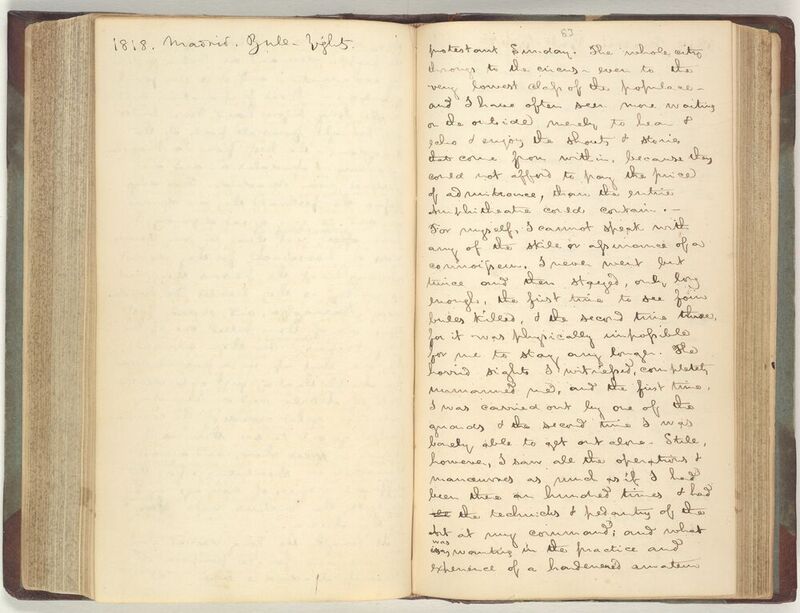

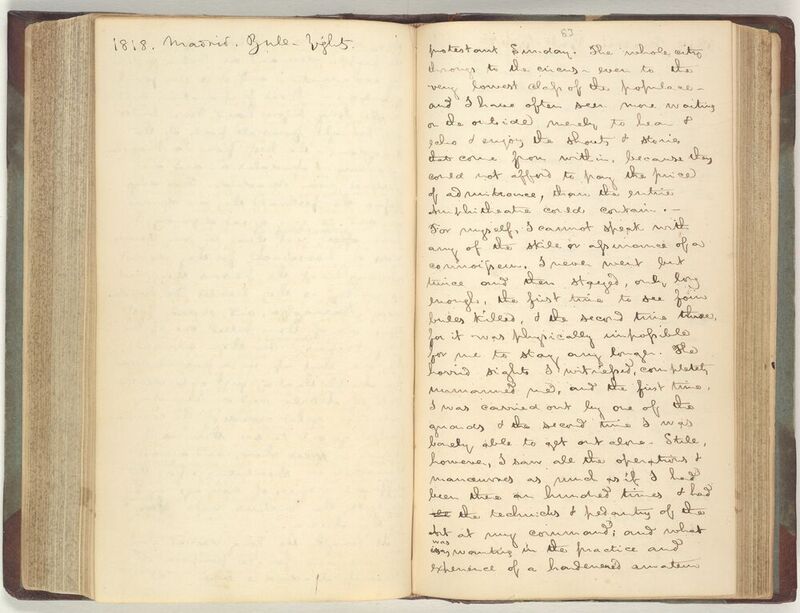

In the entry for "1818 Summer in Madrid," Ticknor dedicates a long passage to bullfighting. Unlike contemporaries such as Washington Irving, Ticknor does not offer a purely romantic portrait of the bullfights. Rather, he describes feeling "unmanned" by them and overcome at the "horrid sights I witnessed." In much of his journal writing, he aims at erudition and educating the imagined reader about the history, geography, or cultural practices of the place he is visiting. In this passage, we encounter a different -- and more human -- side of the author.

-

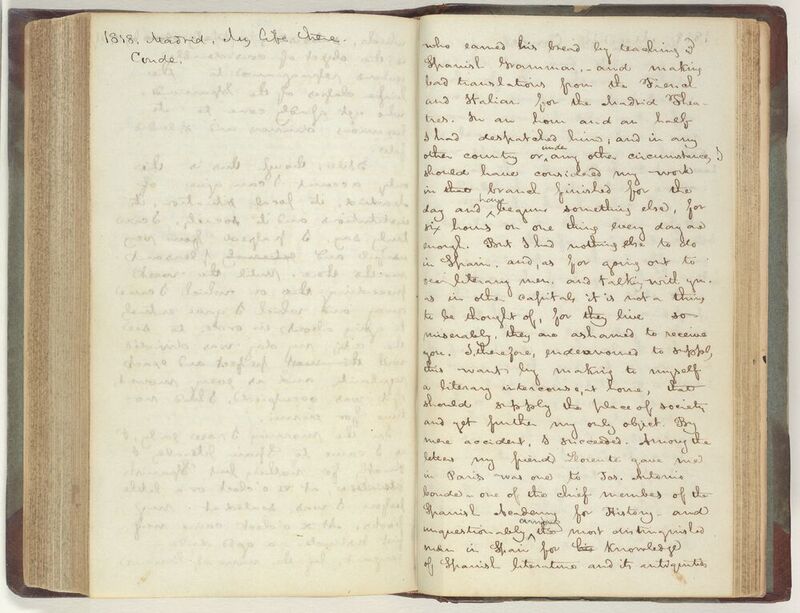

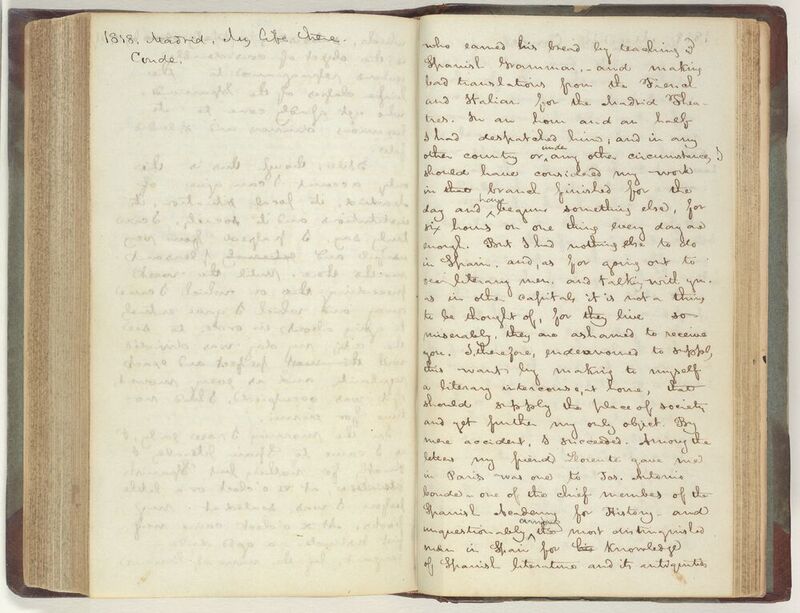

In these journal pages, Ticknor describes his days of study during the summer of 1818 with José Antonio Conde, and other social activities. Ticknor spent long uninterrupted days studying Spanish grammar and literature. "A life," he writes, "better than any I had led in Europe from the complete power it gave me over my own time."

-

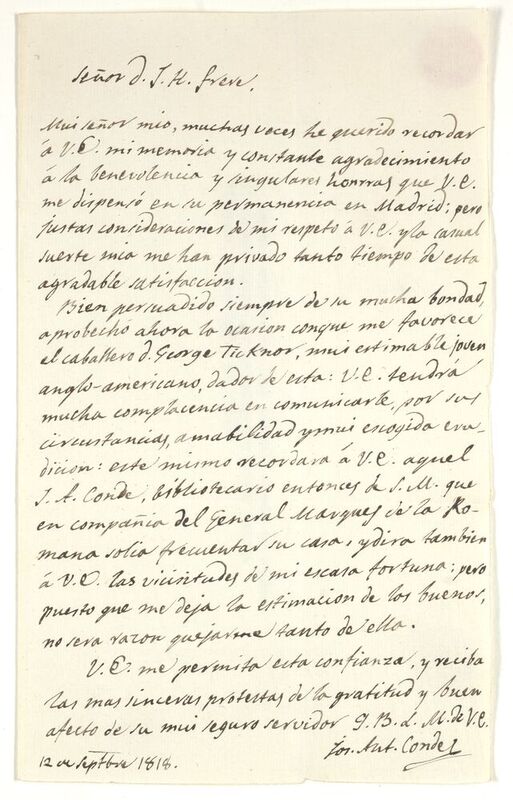

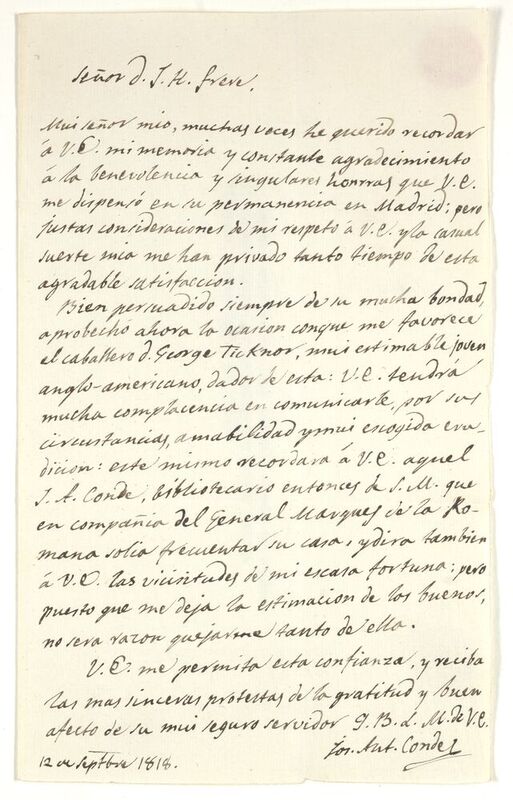

While living in Madrid, Ticknor spent several hours daily under the tutelage of the scholar José Antonio Conde, developing his knowledge of Spanish literature. In this letter of introduction, Conde introduces Ticknor to his associate, John Hookham Frere, an English diplomat and author.

-

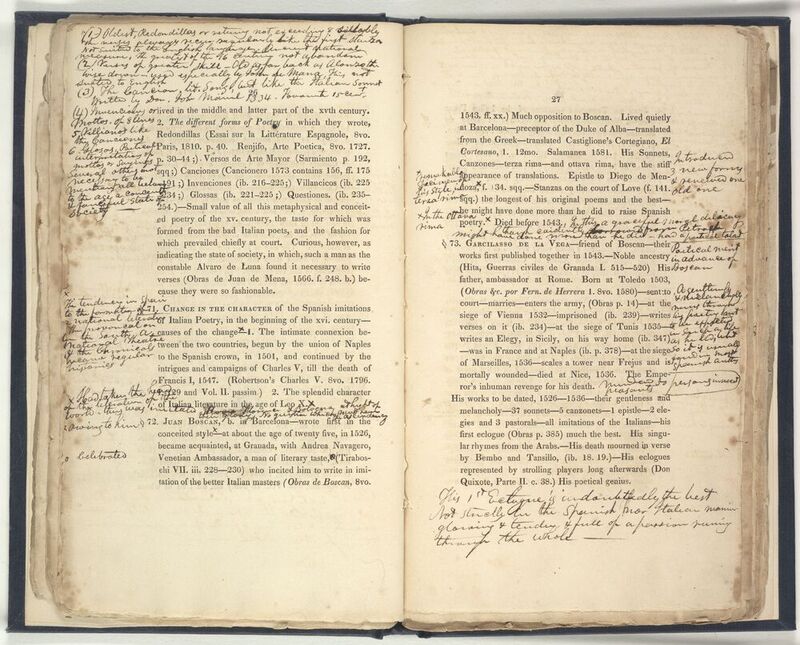

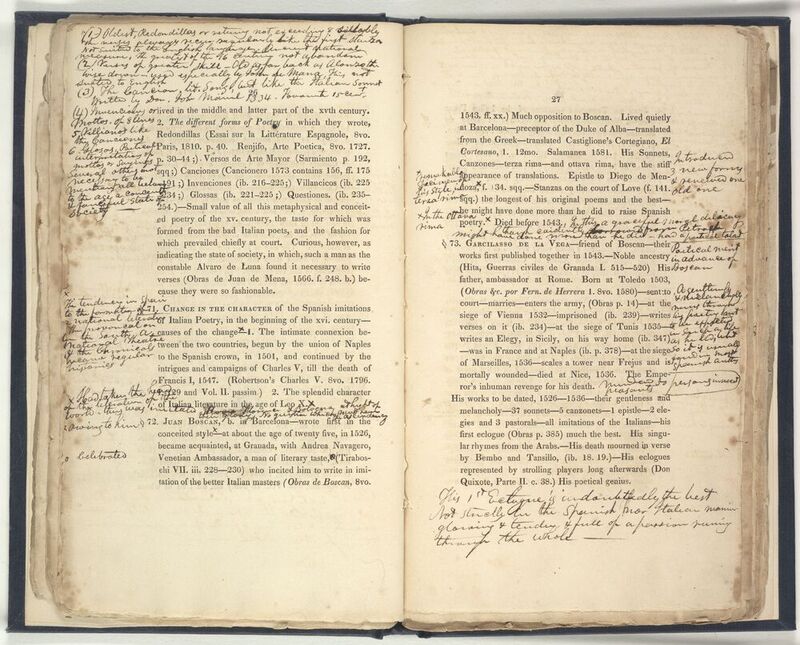

Based on academic lectures delivered to students at Harvard, the Syllabus later informs the History of Spanish Literature, published in 1849. This copy was heavily annotated by one of Ticknor’s students in October 1831.

-

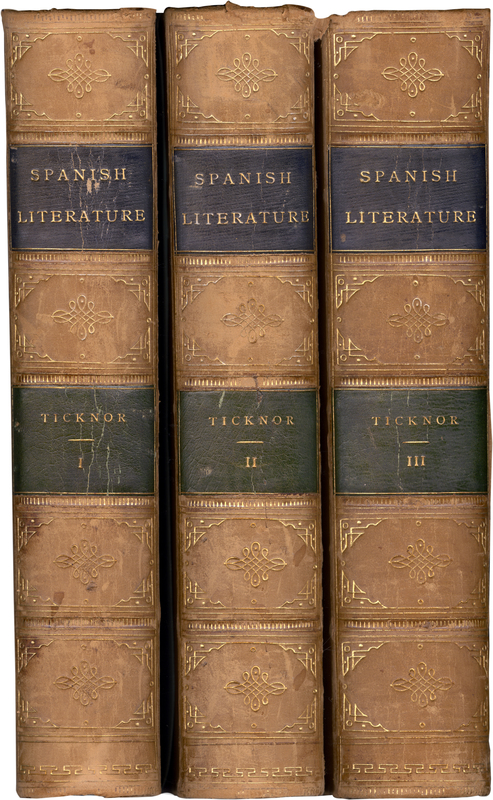

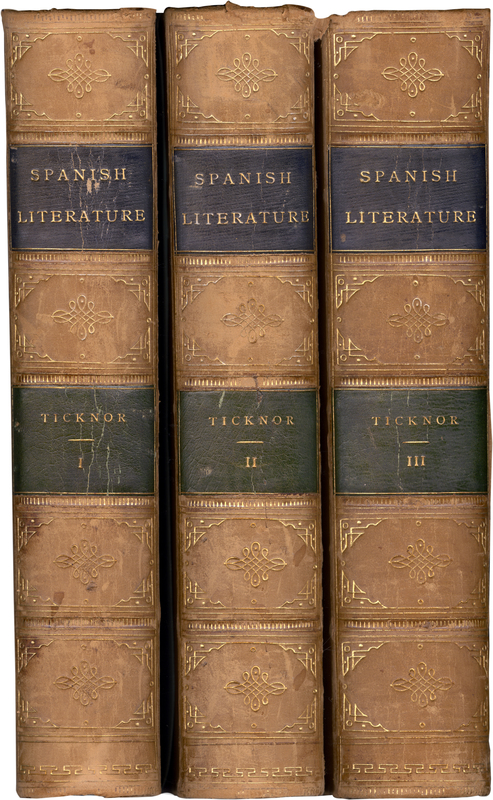

Ticknor’s monumental work was an important text in the field of Hispanic Studies for fifty years after its publication. A book of its time, it linked Spanish literature to notions of national character. The text expresses, in the words of scholar Thomas R. Hart Jr., “the Federalist and Unitarian standards of the Boston society in which [Ticknor] played a leading role.”

-

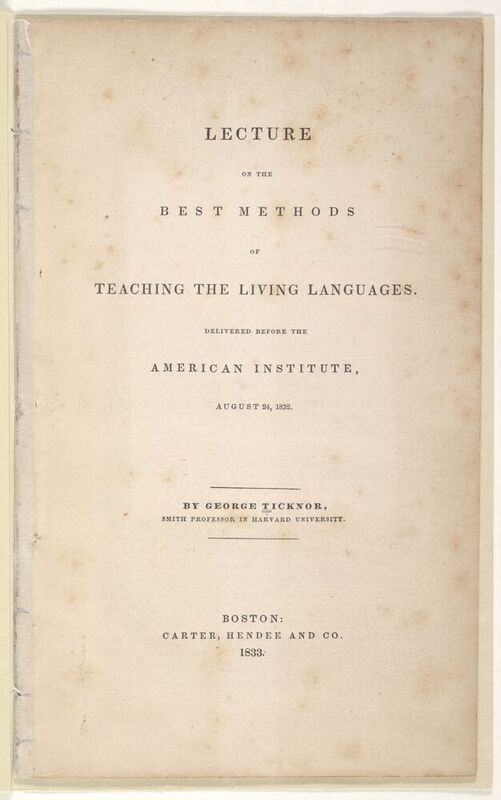

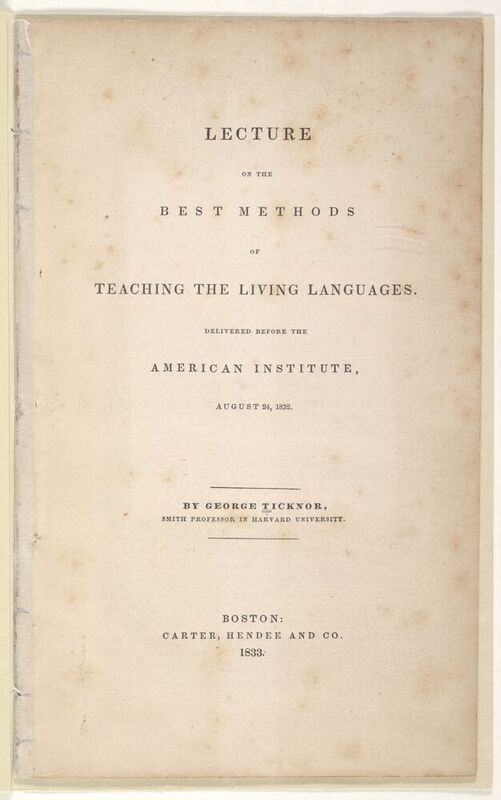

As a professor at Harvard, Ticknor advocated strongly for reform in pedagogical practices at the university. Unlike the teaching of classical languages, he asserts the value of speaking the modern languages in addition to reading them: “The most important characteristic of a living language, -- the attribute in which resides its essential power and value, -- is, that it is a spoken one.”

-

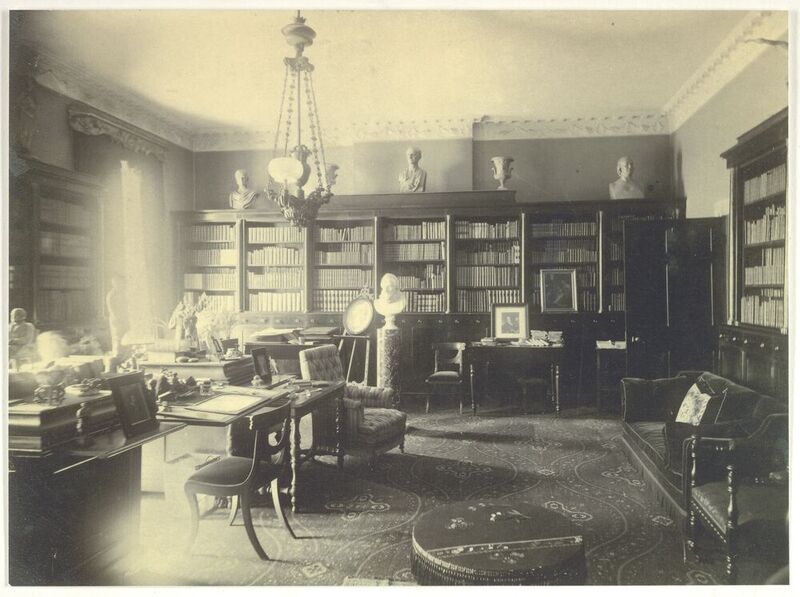

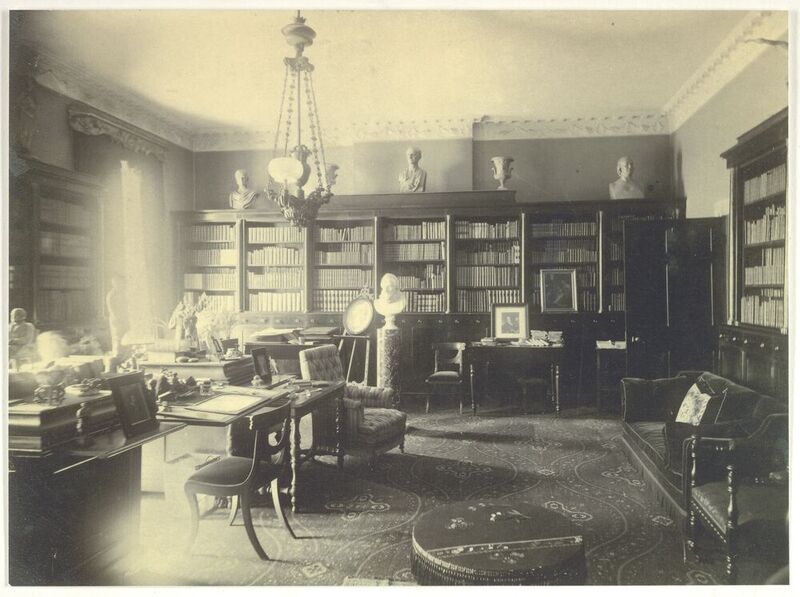

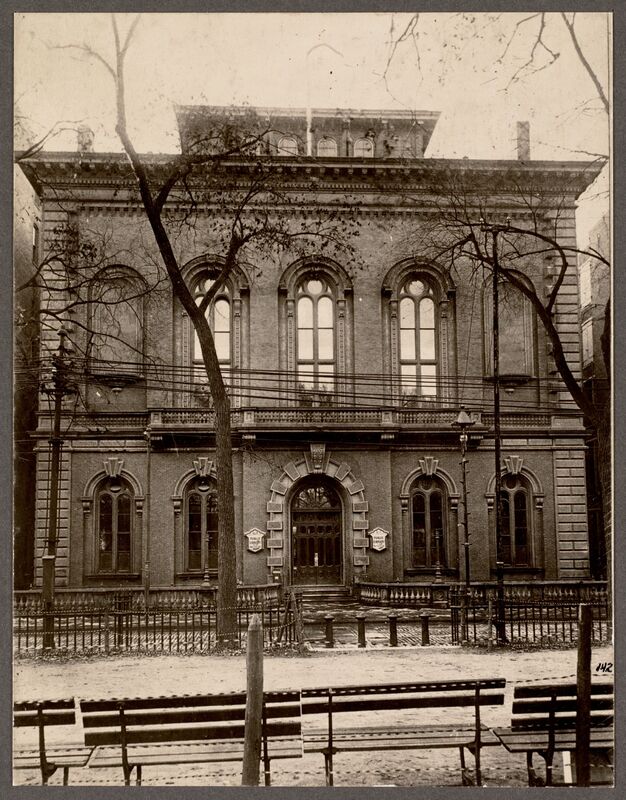

George and Anna Ticknor entertained America’s literati in their home on Boston’s Park Street across from the Boston Commons. Their library provided the perfect setting for literary salons.

-

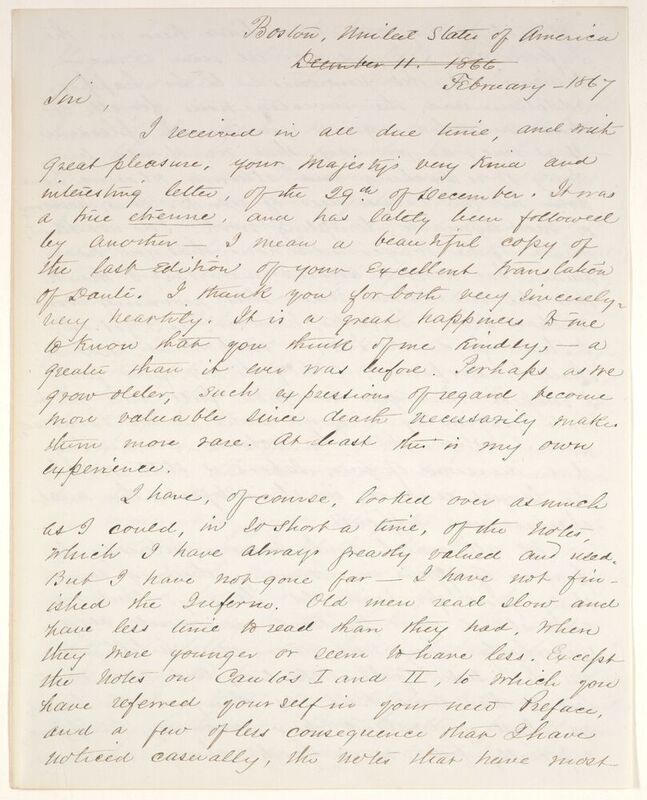

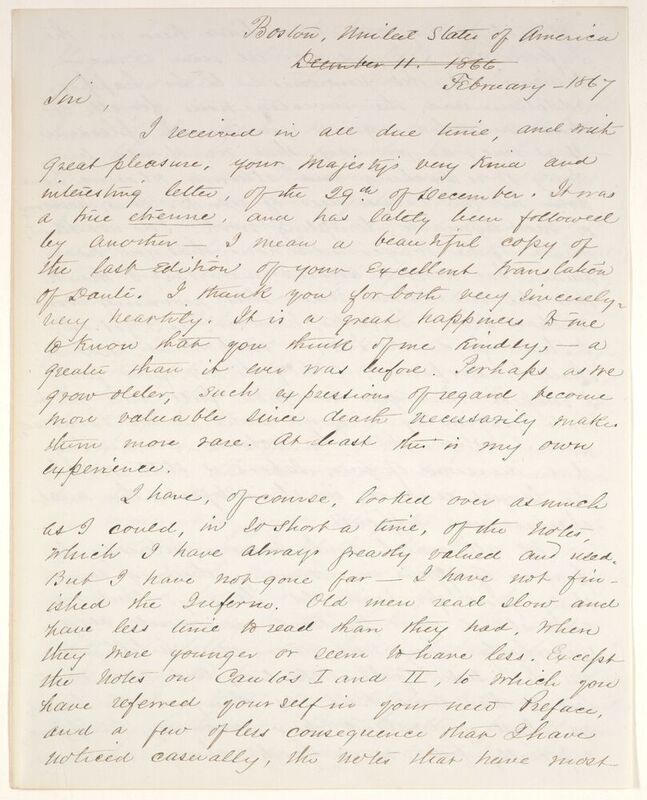

George Ticknor corresponded with teh literati of Europe. Here he discusses translations of Dante with King Johann of Saxony

-

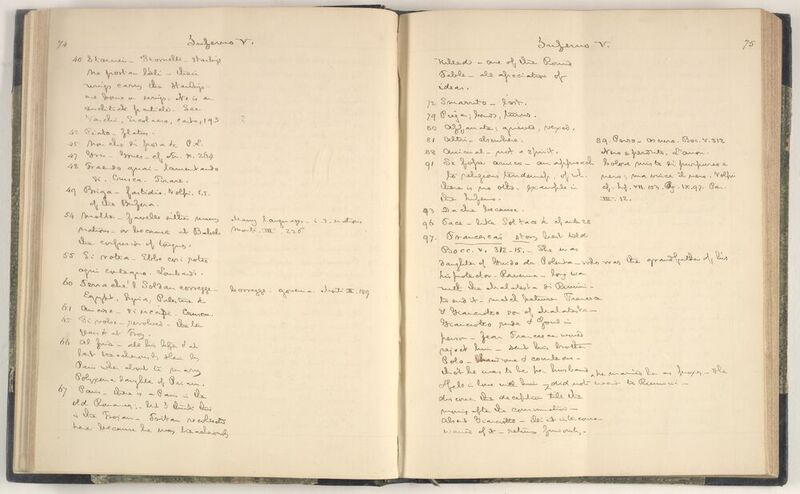

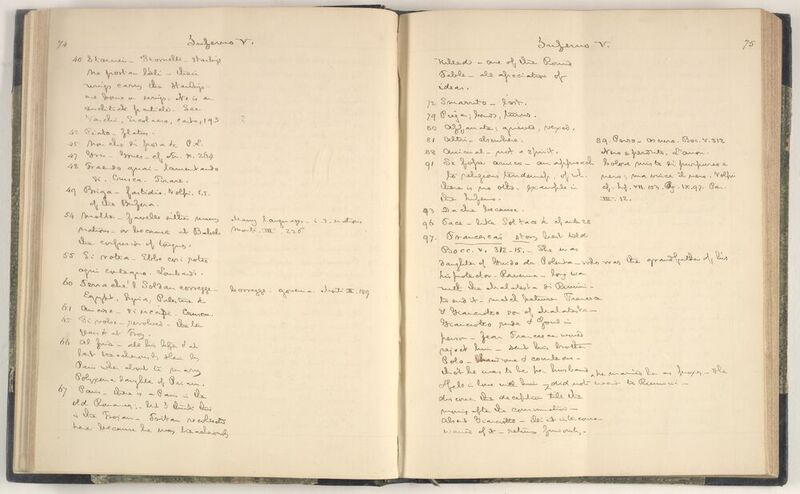

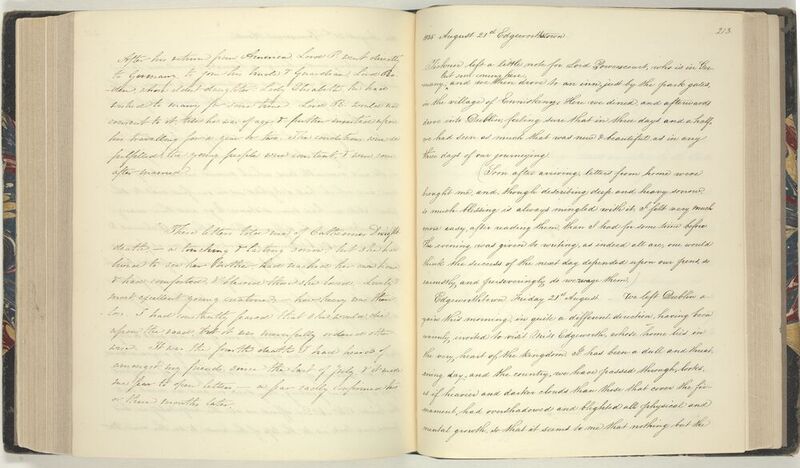

George Ticknor maintained extensive commonplace books to organize his research on various subjects

-

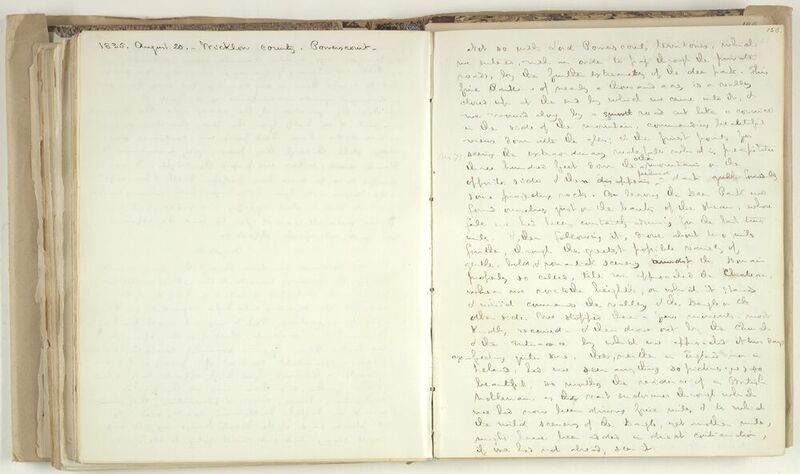

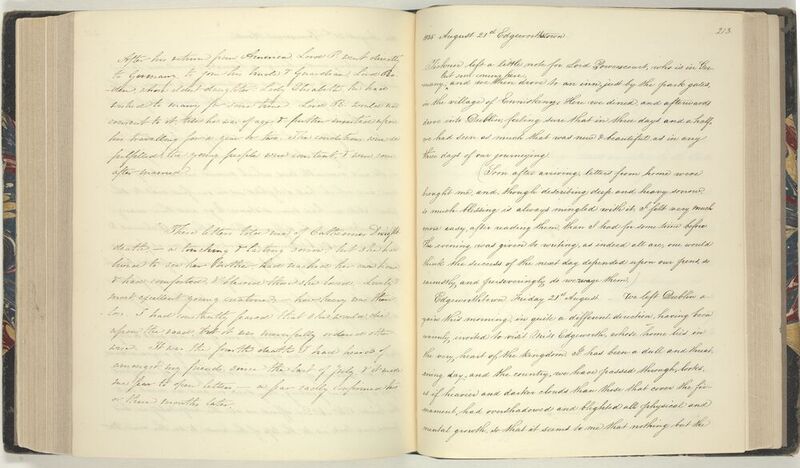

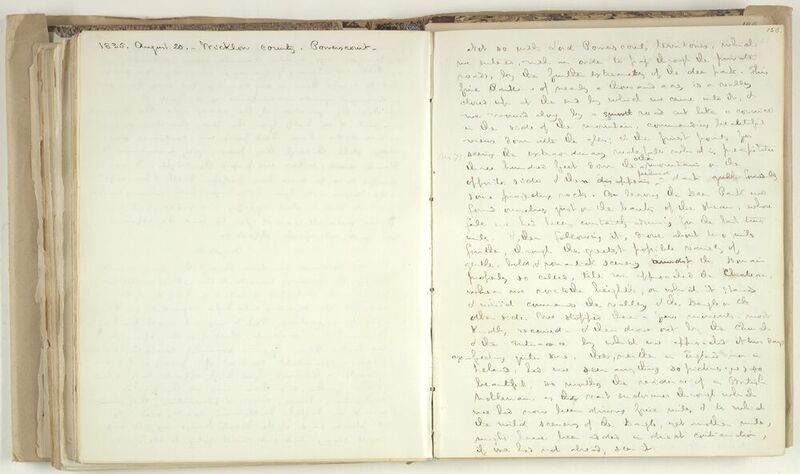

George Ticknor's account of visiting Maria Edgeworth

-

Anna Ticknor's account of visiting Maria Edgeworth

-

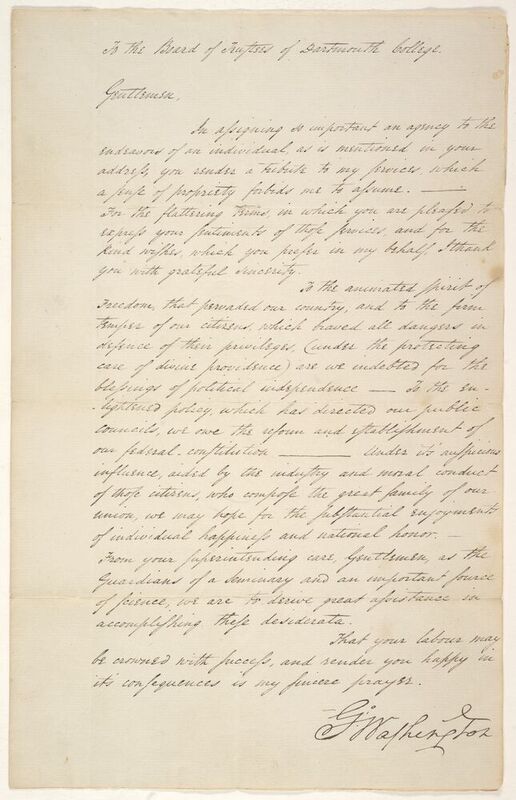

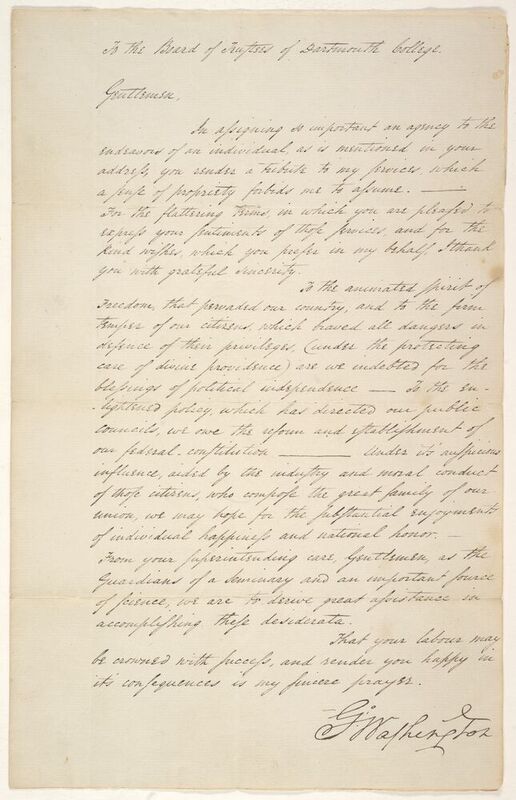

George Washington responding to a letter of congratulations sent to him by the Trustees of Dartmouth College on his inauguration. We do not know how the letter came to be in George Ticknor's collection.

-

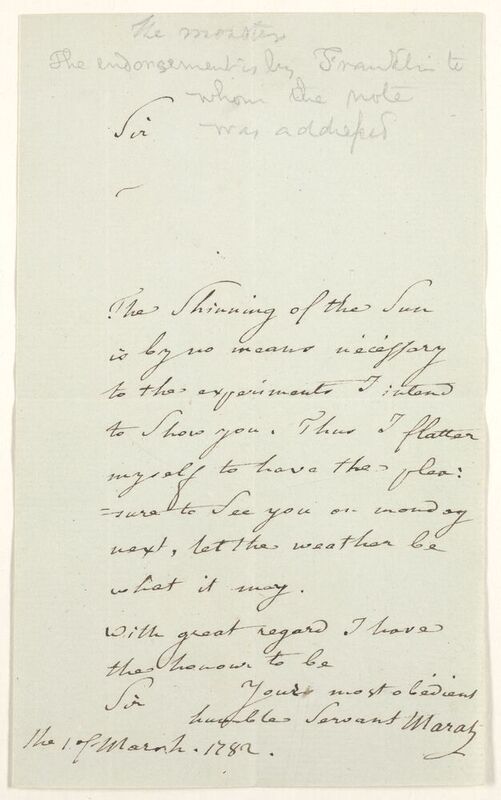

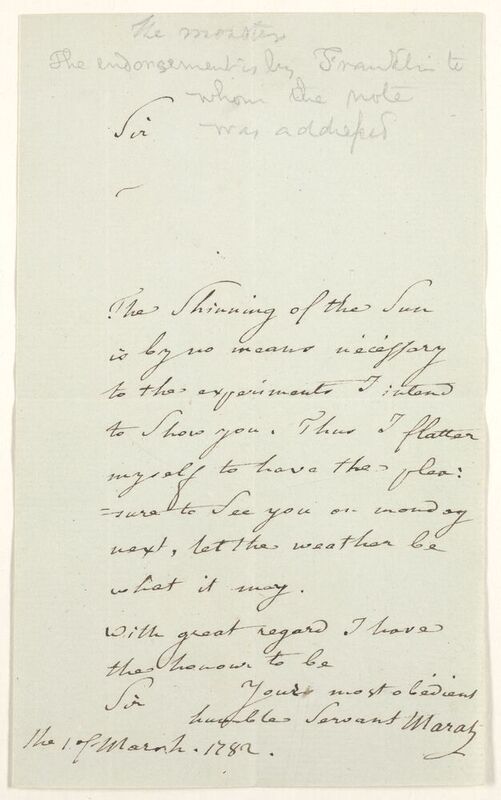

A curious treasure from Ticknor's autograph collection

-

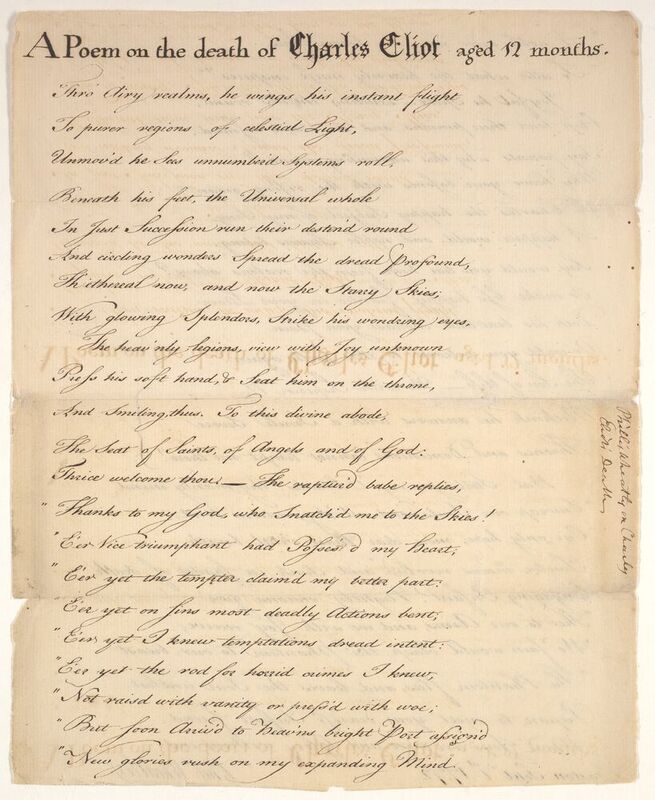

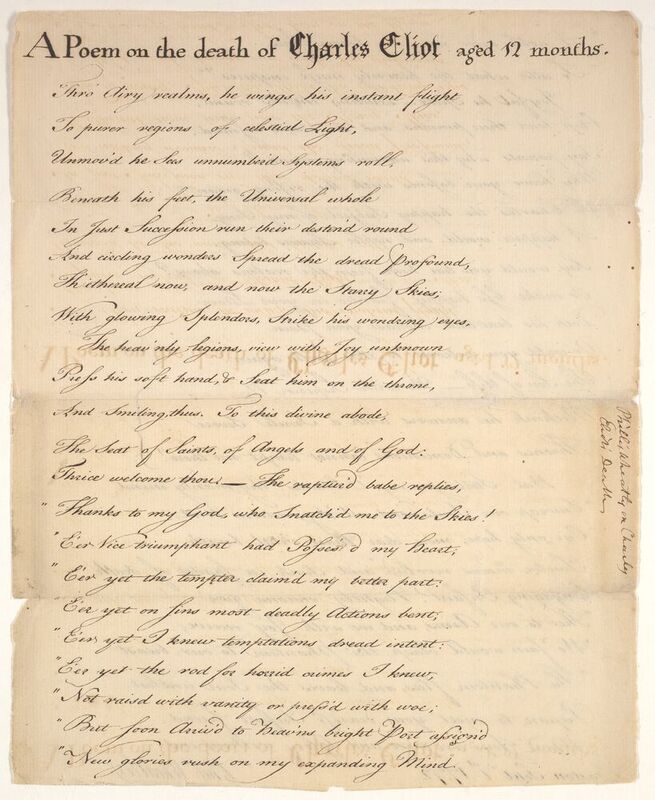

Autograph manuscript copy from Phillis Wheatley

-

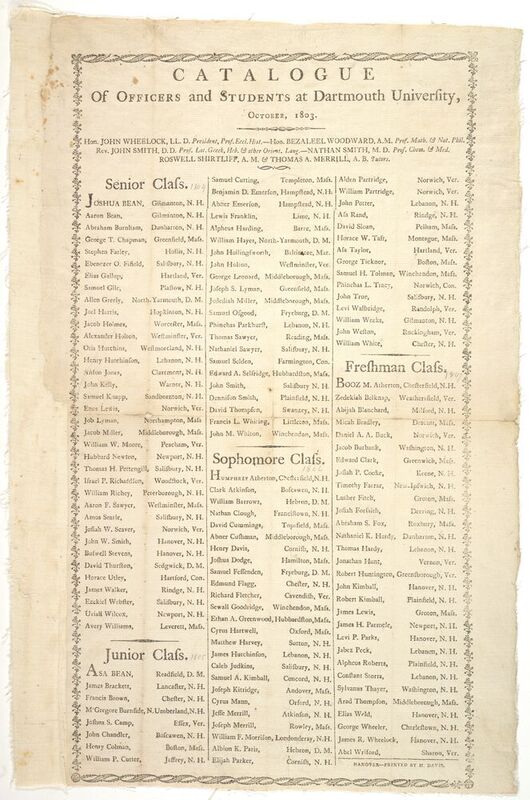

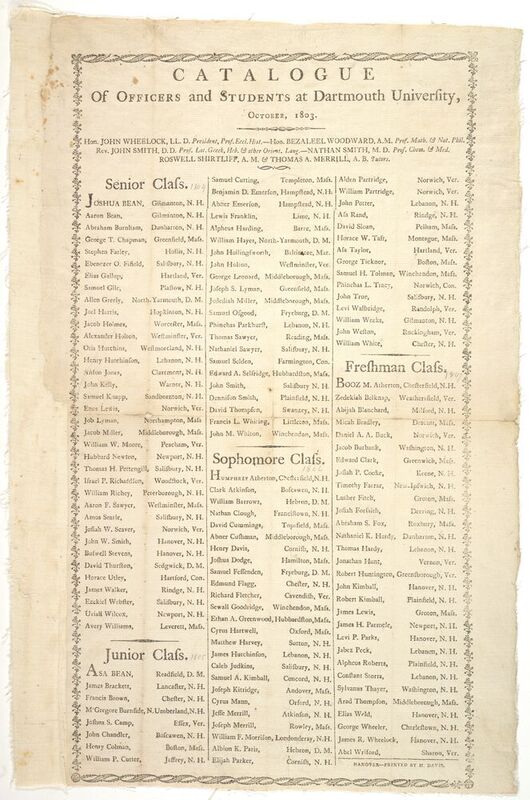

George Ticknor appears in this listing of members of Dartmouth College

-

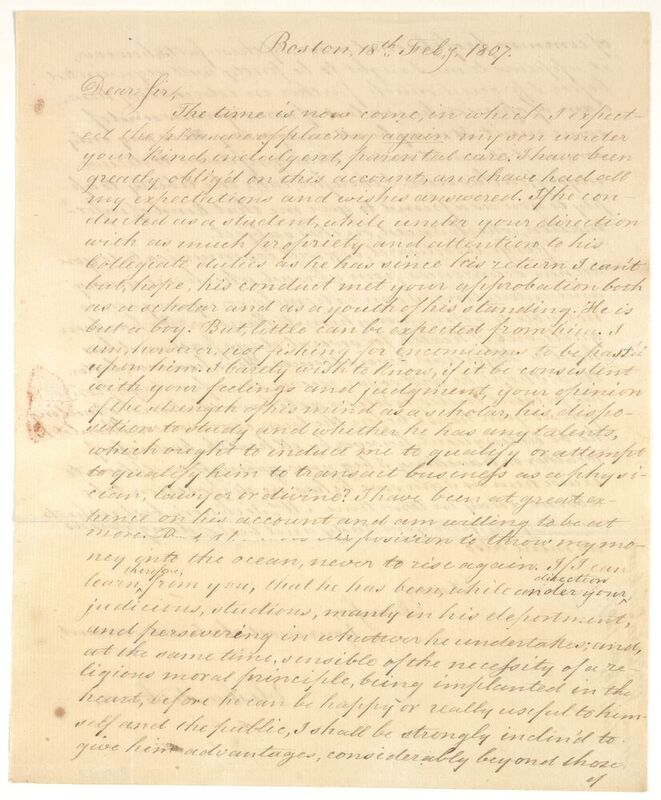

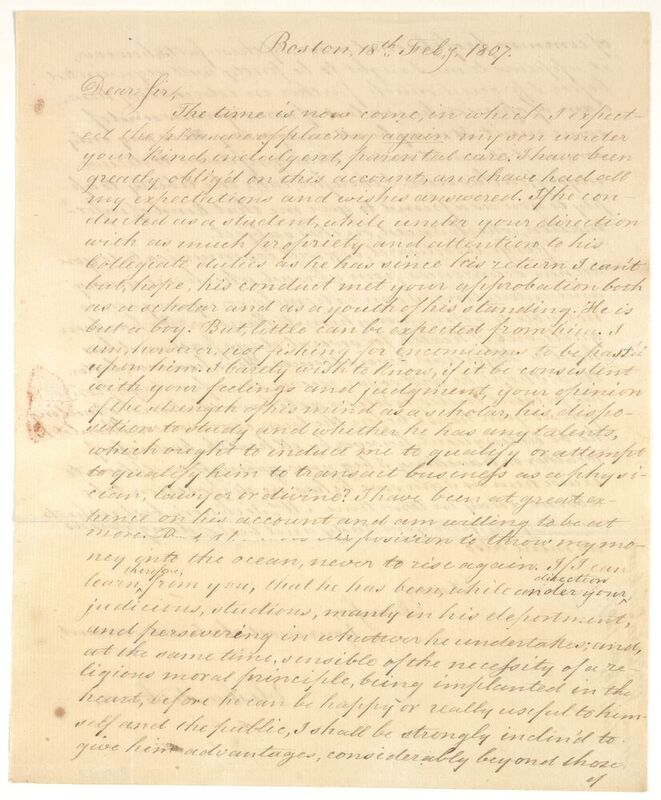

When George was about to graduate, his father, Elisha, questioned John Wheelock on his future prospects to determine if he should invest more in the young man’s education.

-

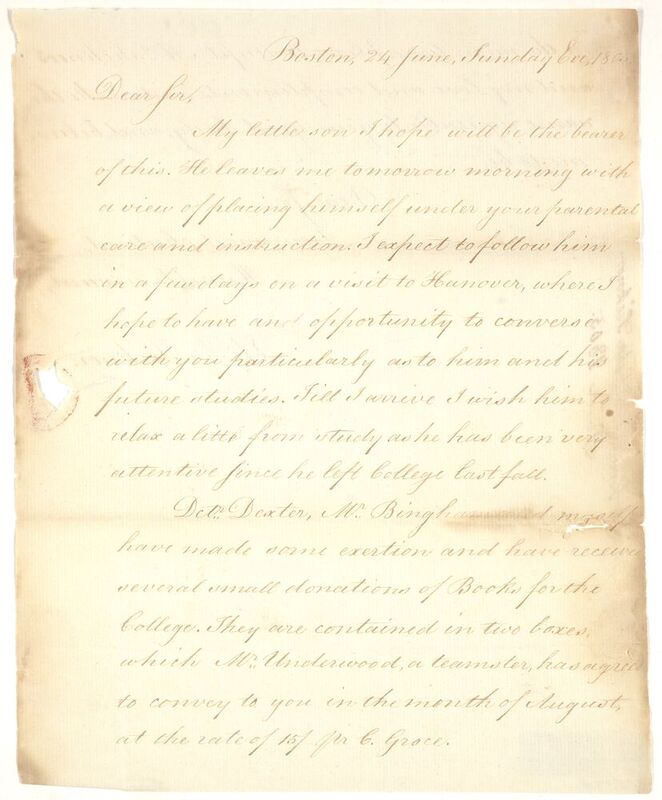

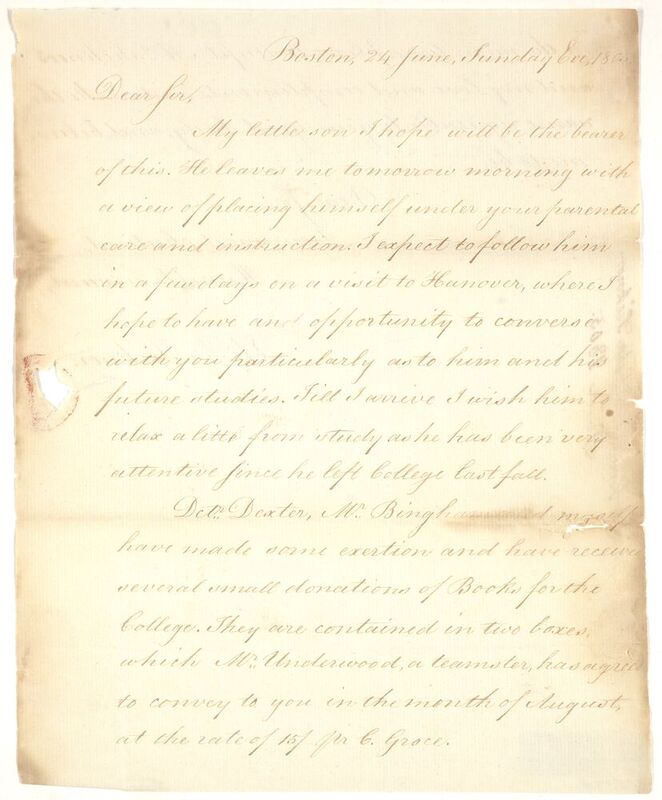

“My little son I hope will be the bearer of this. He leaves me tomorrow morning with a view of placing himself under your parental care and instruction.”

-

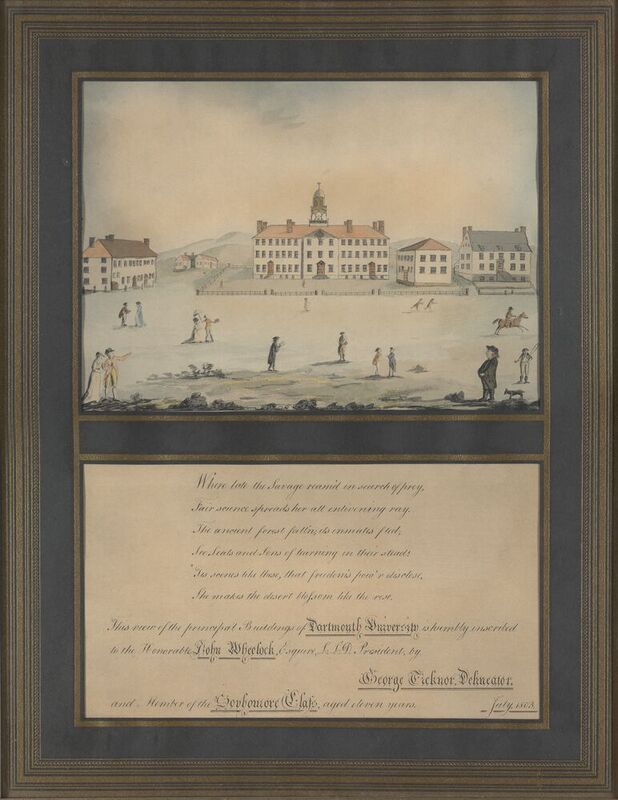

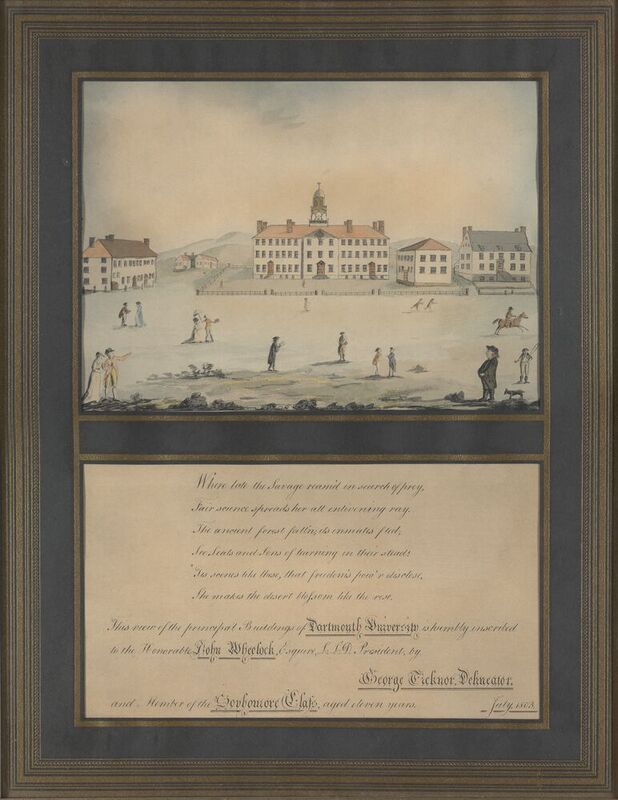

Painted by George Ticknor when he was eleven years old, this is one of the earliest depictions of Dartmouth.

-

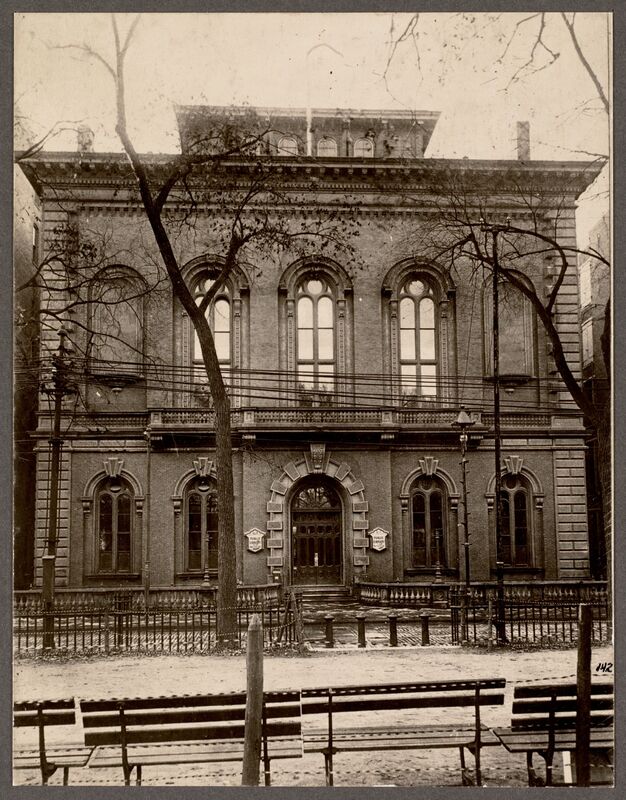

Boston Public Library, Boylston Street. Photograph. 1858.