"… to study – not men, but books"

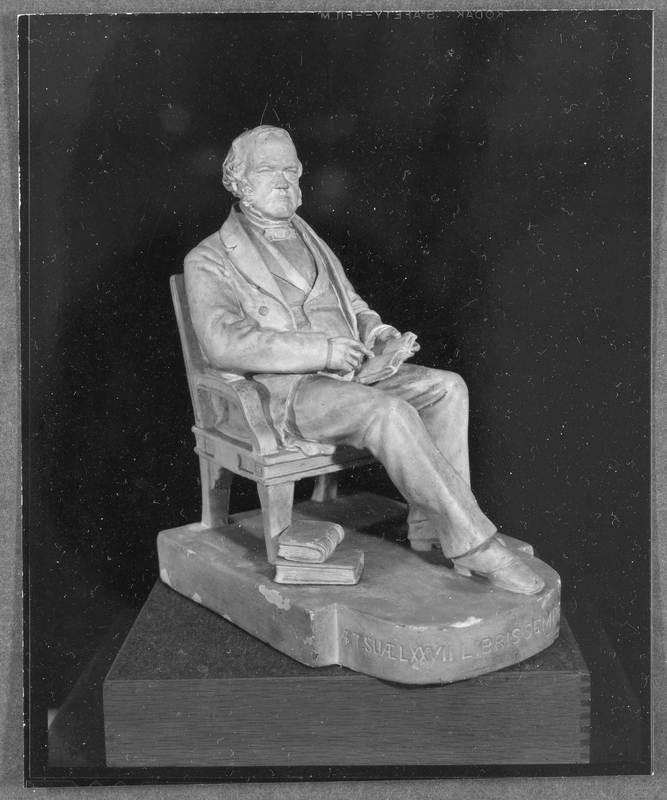

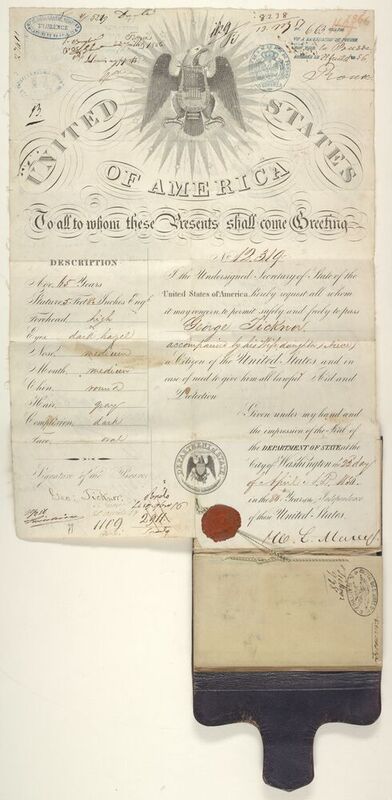

George Ticknor moved in Boston high society. But his cosmopolitan world was broader than just Boston: he made three trips to Europe over the course of his life to broaden not only his own intellectual and social horizons, but also those of his fellow citizens. His first trip to Europe in 1815 was for knowledge. He knew his education in the United States was provincial and not enough. "I was idle in college and learnt little" at Dartmouth, he later reflected. He took on tutors, but soon found he had gone as far as he could with his lessons. He wrote to a friend, "The whole tour in Europe I consider a sacrifice of enjoyment to improvement. I value it only in proportion to the great means and inducements it will afford me to study—not men, but books." In the following excerpts from his diary, Ticknor describes his first two semesters at the University of Göttingen:

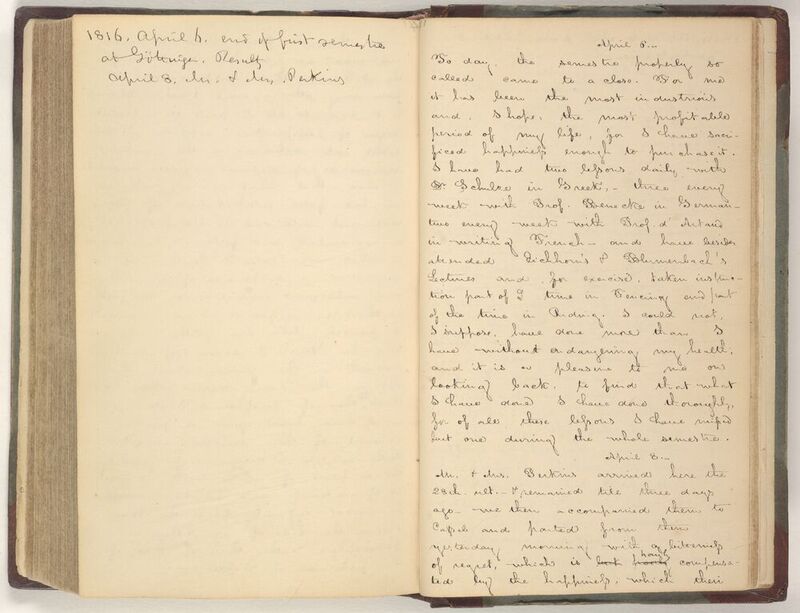

1816 April 6. Göttingen. End of first semester at Göttingen. Results. Today the semester properly so called came to a close. For me it has been the most industrious and, I hope, the most profitable period of my life, for I have sacrificed happiness enough to purchase it…

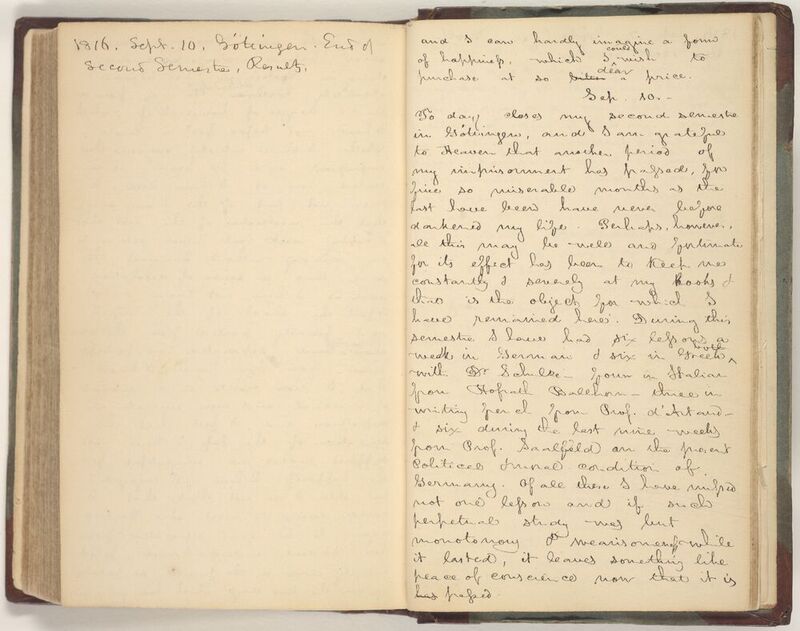

1816 Sept. 10. Göttingen. End of second semester. Results. Today closes my second semester in Göttingen, and I am grateful to Heaven that another period of my imprisonment has passed, for five so miserable months as the last have been have never before darkened my life. Perhaps, however, all this may be well and fortunate for its effect has been to keep me constantly and severely at my books and that is the object for which I have remained here.

Correspondence

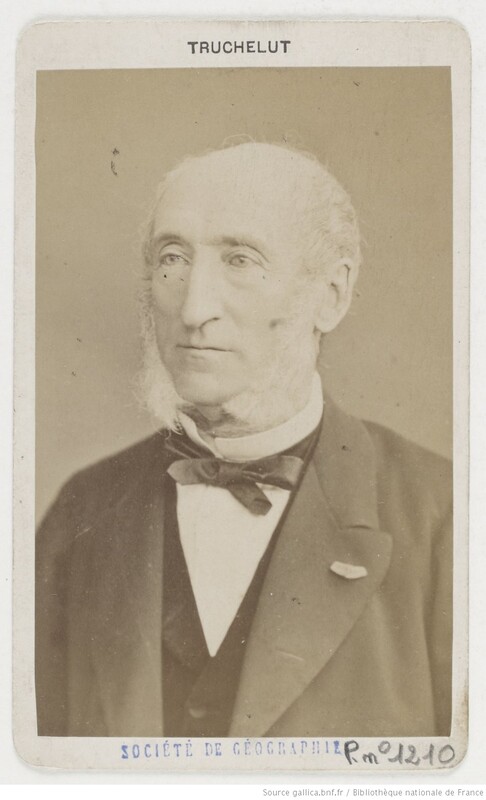

Armed with letters of introduction from prominent Americans like Thomas Jefferson, Ticknor made friends and acquaintances with scholars, politicians, and men of letters all over Europe. In America, Ticknor kept up these relationships through letters. Europeans were curious about the young United States and sometimes anxious about its growing power. In this letter to Ticknor, Michel Chevalier writes of Europe's unease:

Savez-vous que de vous voir réussir dans cette tentative audacieuse devient pour nous Européens un légitime sujet d'inquietude. Ce voir en effet rien moins qu'un commencement du Conquête de l'ancien monde par l'amérique.

[Do you know that seeing you succeed in this bold endeavor is a real concern for us Europeans? This is indeed nothing less than the beginning of the American conquest of the Old World.]

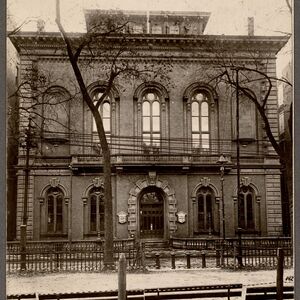

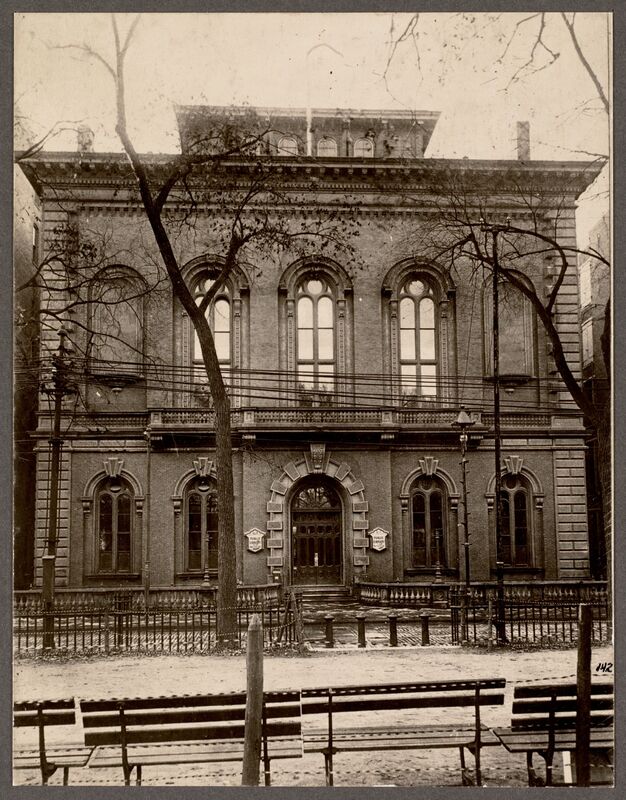

The Boston Public Library

Ticknor, aged 65, returned to Europe for the last time to buy books for the Boston Public Library. He believed that free and open public libraries would promote lifelong learning among the people if the libraries would loan books for free, have many copies of popular works, and allow the public to ask the library to purchase books. These were radical ideas at the time. Most libraries charged fees and kept only books suited to well-educated readers. Ticknor's ideas ultimately prevailed.