A Passion for Hispanism

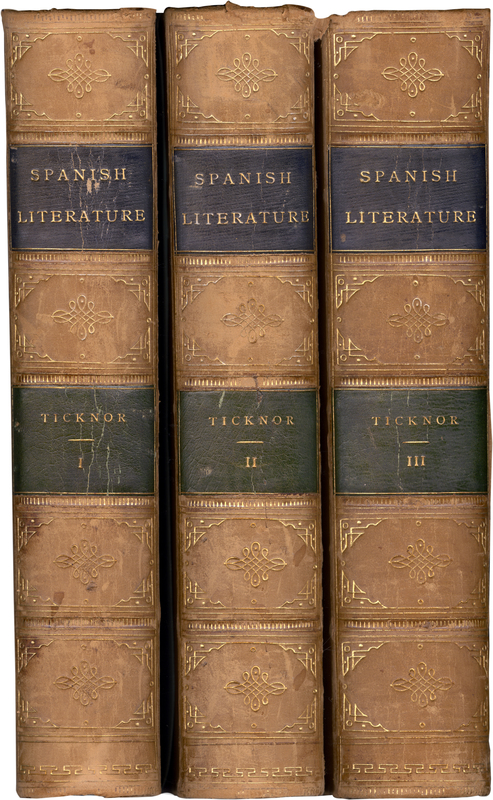

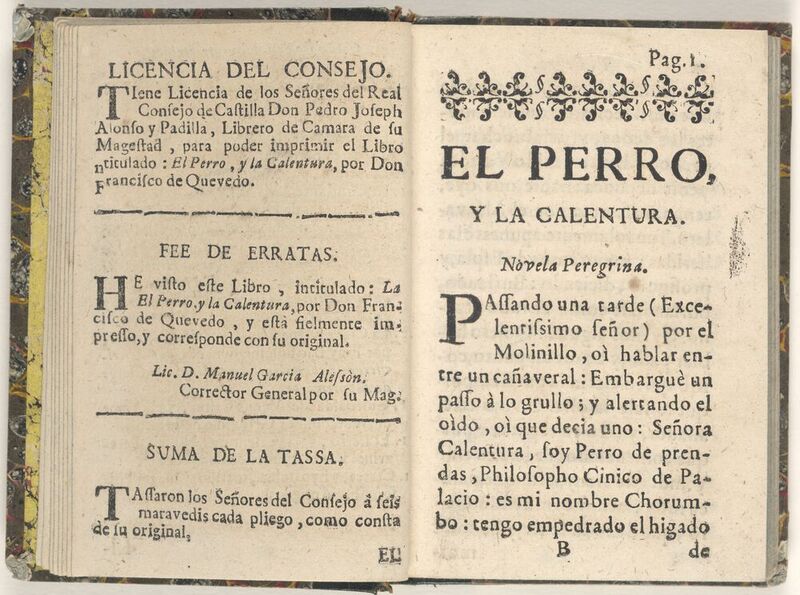

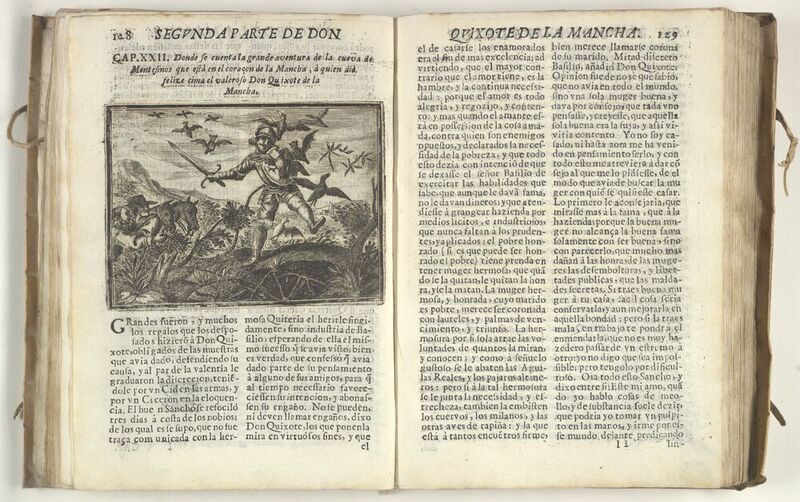

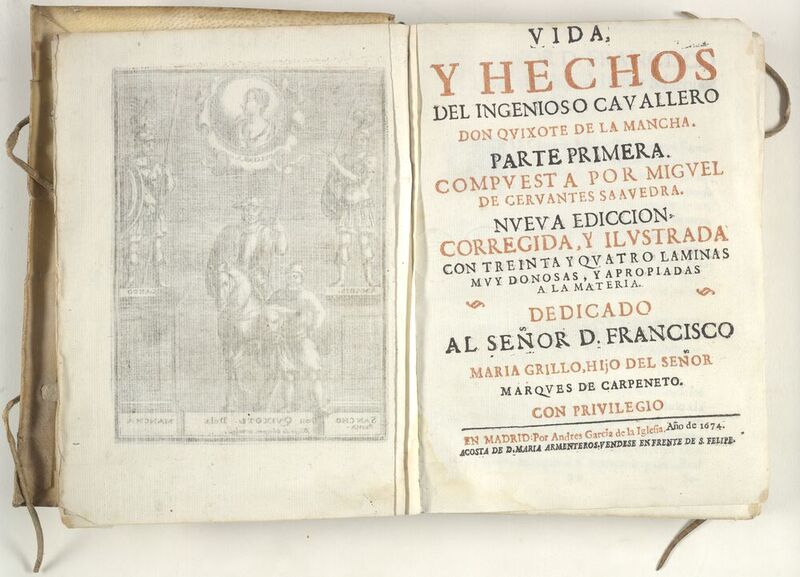

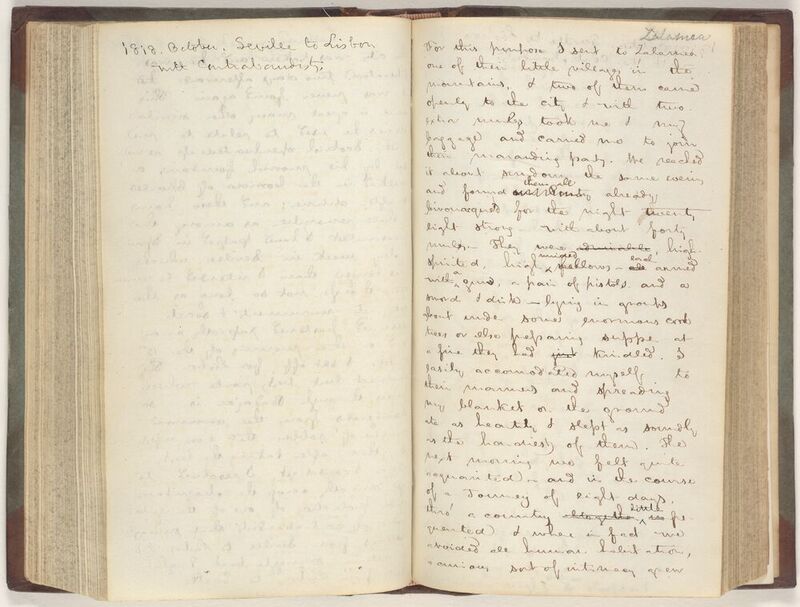

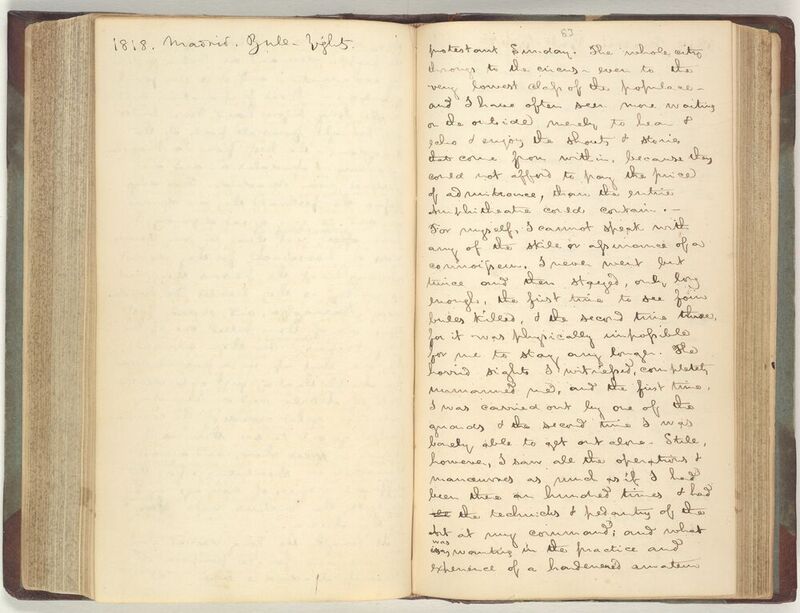

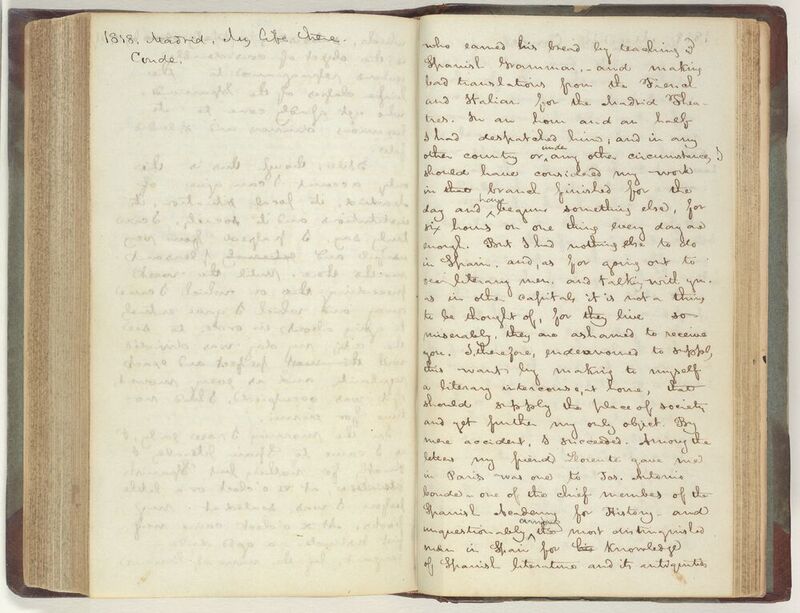

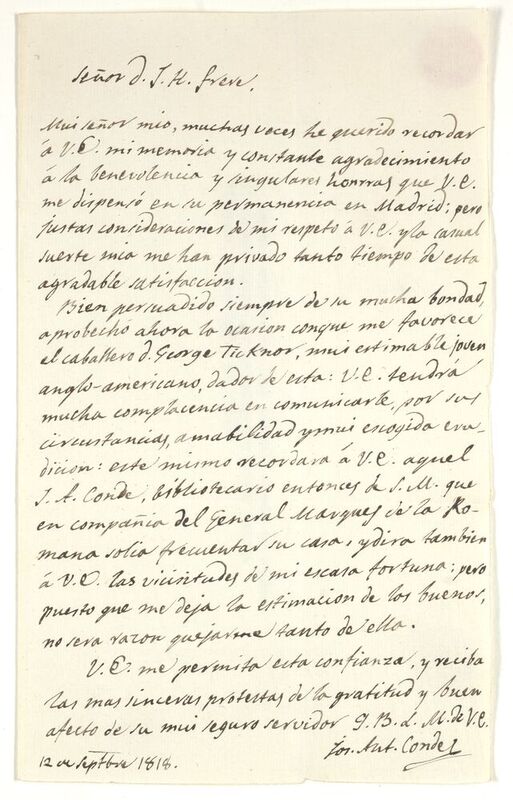

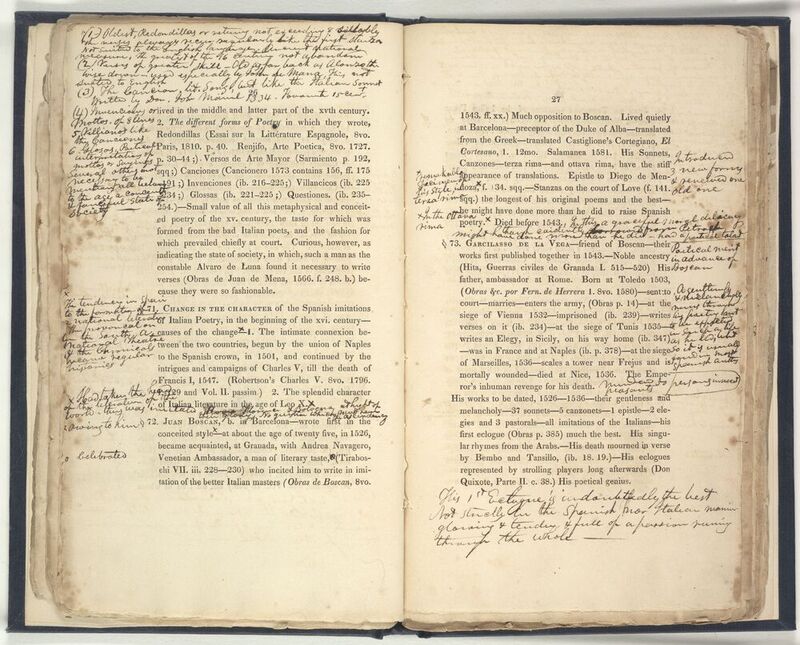

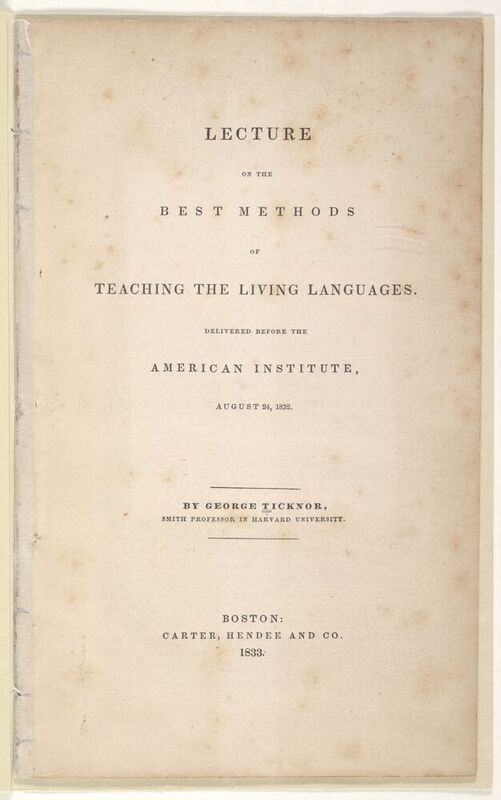

George Ticknor played a leading role in the establishment of the study of modern languages in North America. While a student in Europe, Ticknor was invited to be the inaugural Smith Professor of French and Spanish Languages and Literatures at Harvard College, where he taught until 1835. To prepare for this position, Ticknor left his studies at the University of Göttingen in Germany and traveled to France, and later Spain, to dedicate himself to the intensive study of French and Spanish literatures. During this period, he developed a passion for the literature of Golden Age Spain. That, coupled with his collecting of Spanish-language materials, led Ticknor to produce the three-volume History of Spanish Literature (1849), later translated into Spanish and other languages. This work was unparalleled for providing a comprehensive study of authors such as Miguel de Cervantes, Lope de Vega, Calderón de la Barca, and others. His collecting habits allowed him to amass the most significant library of Spanish literature in the United States in the nineteenth century.

What is Hispanism?

Hispanism refers to an academic discipline and intellectual practice devoted to the study of Spanish and the literature and cultures of the Spanish-speaking countries and regions.