Anna Sarvira

A graduate of the National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture in Kyiv, Anna Sarvira is an illustrator, curator, and art director currently living in Cologne. She’s a co-founder of the Pictoric Illustrators Club. Shortlisted twice in 2017 and 2019 as one of the 75 world’s best illustrators at the Bologna Children’s Book Fair, she received an Adobe Community Fund grant and a scholarship from the German Academy of the Arts in 2022 and was shortlisted for the Joseph Binder Award. Anna has worked with UNICEF, Museum of Modern Art New York, Goethe Institute, British Council, UN Women, Coca-Cola, Penguin Books, Blue Rabbit Publishing, Glowberry Books, Lyuta Sprava, Republik, and Hohe Luft.

Her works have been exhibited in Ukraine, Germany, Portugal, Poland, Hungary, Georgia, Italy, Japan, Spain, France, Sweden, Finland, South Korea, Canada, and the USA.

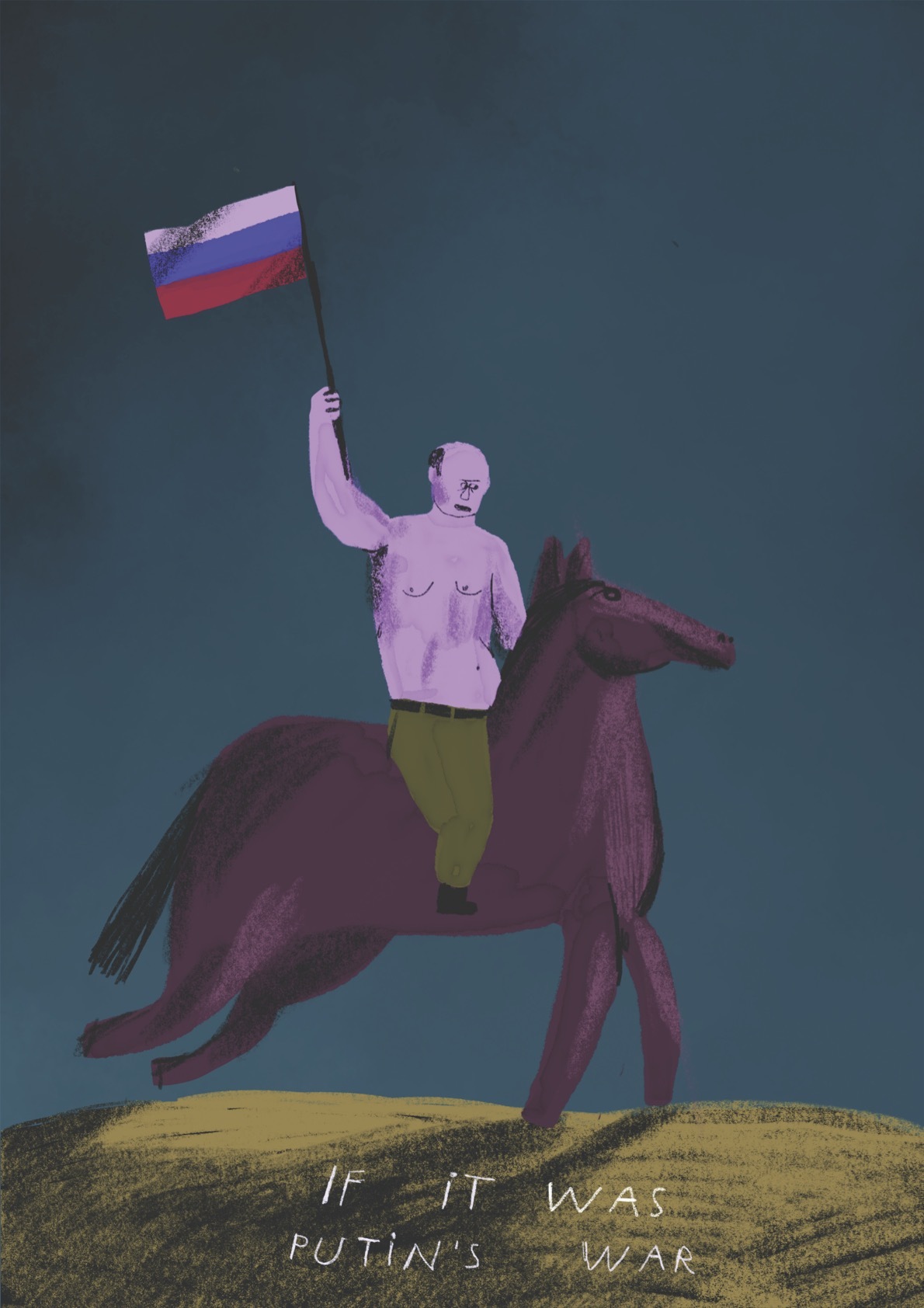

“What I imagine when people (still!) call this war ‘Putin’s war.’”

In the early days of the full-scale invasion, there was a widespread tendency in the West to call the Russian-Ukrainian war—‘Putin’s war.’ Some still call it that way. The problem with this definition is that it holds only the Russian dictator responsible for the war, neglecting the collective guilt of the Russian people whose (in)actions had a horrifying outcome. It is also argued that it’s not Putin who hits the button in fighter jets bombing Ukrainian hospitals and schools or rapes women in the occupied towns—other people commit these atrocities, and they must be held accountable. The artist implies that if only Putin himself was the problem, he could’ve been liquidated in no time by his own people who disagreed with his genocidal politics. But that’s obviously not the case.

The Russian-Ukrainian war is not just ‘Putin’s war’—there are thousands of people committing atrocities and millions supporting Russia’s genocidal politics.

"That’s the cover I did at the beginning of March for the Hungarian magazine, 168 Ora. Back then, people were stopping tanks with their bare hands. Back then, we didn’t know how massively Russian soldiers would rape, torture, and kill civil Ukrainians."

Since the early days of the large-scale war, videos showing the perseverance and courage of the Ukrainian people have been widely shared on social media. One of them shows a Ukrainian man, a local of Bakhmach in the Chernihiv region, bravely blocking a Russian tank barehanded and pushing back on it until the military vehicle is forced to slow down. The footage has been compared to the iconic photo of an unidentified Chinese man who stood in front of a procession of tanks in Tiananmen Square in Beijing in 1989.

“This is the only dove of peace that could help Ukraine right now. I am scared of weapons. I am scared of the war. I would like the situation to be different. I would prefer if the problems could be solved by negotiation. But no negotiations will help if your enemy’s goal is to eliminate you. Annihilate Ukraine as a nation, erase the Ukrainian culture, ban the Ukrainian language, and suppress everybody who disagrees. When russians took over Ukrainian cities, they were killing, torturing, and raping. And then, they forced local civilians to go to war. Like they do in Donetsk and Luhansk now. Ukraine needs weapons.”

The artist builds her image on the contrast between peace, symbolized here by a dove carrying an olive branch, and war, visualized by a soldier and Javelin anti-tank missile. In times of unprovoked genocidal war of aggression, it is only by the weapon that peace can be restored, the artist claims. In March and April 2022, the Ukrainian government and citizens called on the West with an urgent plea to ‘close the sky,’ that is, to provide more weapons and, in particular, anti-aircraft systems so that Ukraine could protect its people and infrastructure from Russian missiles and air strikes. Lightweight, shoulder-fired Javelins became one of the first weapons that western countries supplied to Ukraine en masse.