-

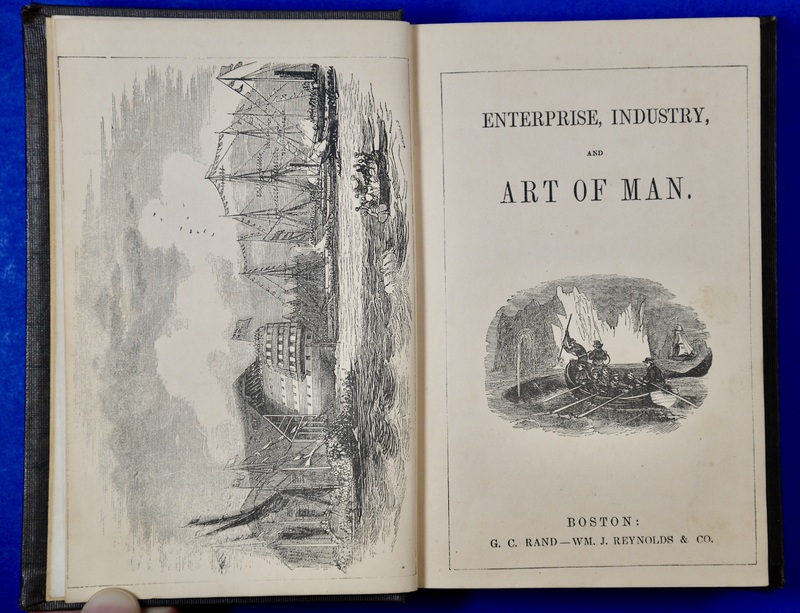

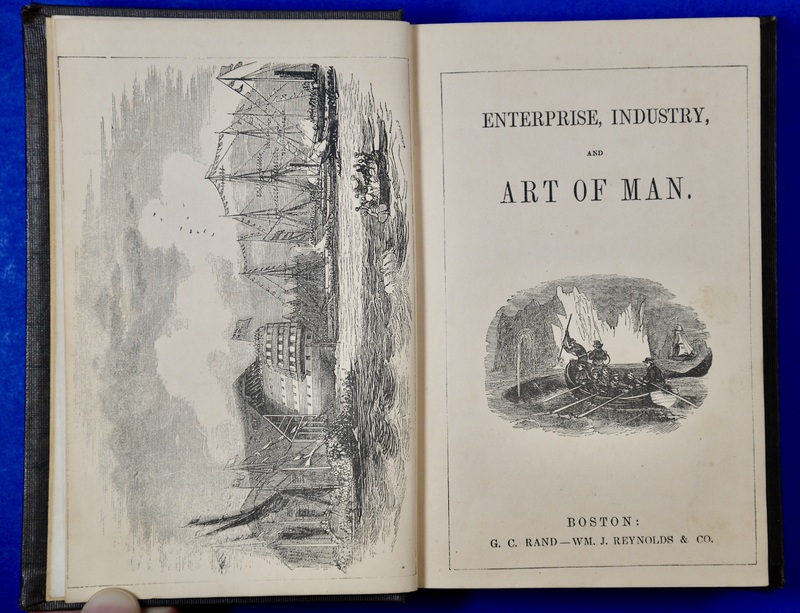

Written as an ode to the power of global trade, Enterprise, Industry and Art of Man is representative of the sense of awe Europeans felt about their ability to “tame” wilderness and harness it to better society during the Industrial Revolution. In the volume’s preface, Goodrich marvels at the origins of the material comforts in his personal study, including a piano whose materials hailed from forests of Brazil, Maine, and elephants in Africa. Meditations on his Argand lamp are of particular interest for “its oil [that] once dwelt in the head of a whale seventy feet in length, and which sloughed the Pacific for half a century.” As this quote (and illustration above suggest), the efficiency and global reach of extractive enterprises such as whaling were examples of progress and sources of pride in the minds of Western cultures.

-

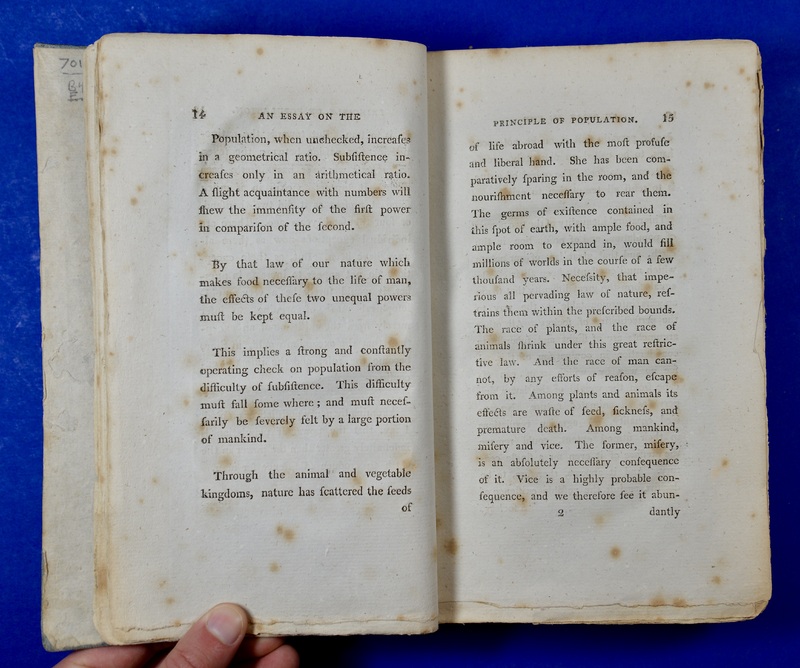

Our first edition of this famous work by Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) was published anonymously so as to avoid backlash. Malthus’ book contrasted with the optimistic views of Enlightenment thinkers such as Jean Jacques Rousseau by warning of future difficulties that would arise as human population growth outpaced food production. This essay sparked discussions about the environmental impacts of exponential human population growth, along with highlighting problems like poverty and famine.

-

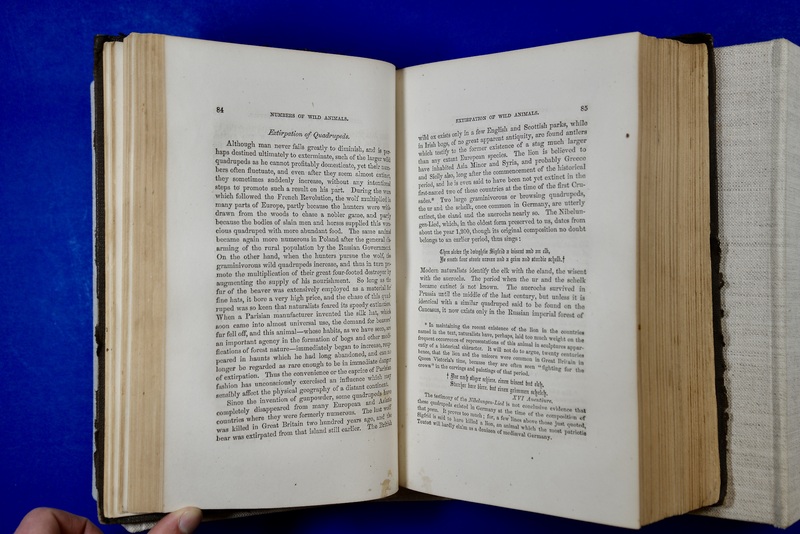

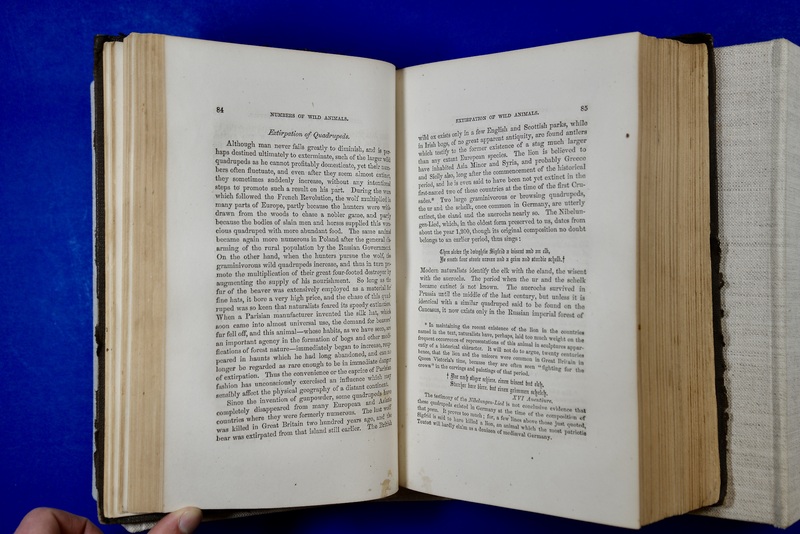

George P. Marsh (1801-1882), Dartmouth Class of 1820, is considered America’s first environmentalist and among the first American natural historians to comment on species extinction. Man and Nature raised concerns about the destructive global impacts of human activities on the environment, including plants and animals. For instance, Marsh describes how European demand for beaver fur nearly doomed the industrious mammal to extinction in the Americas: “Parisian fashion has unconsciously exercised an influence which may sensibly affect the physical geography of a distant continent.” Man and Nature was received favorably and helped sparked the Arbor Day movement, the establishment of forest reserves and the national forest service.

-

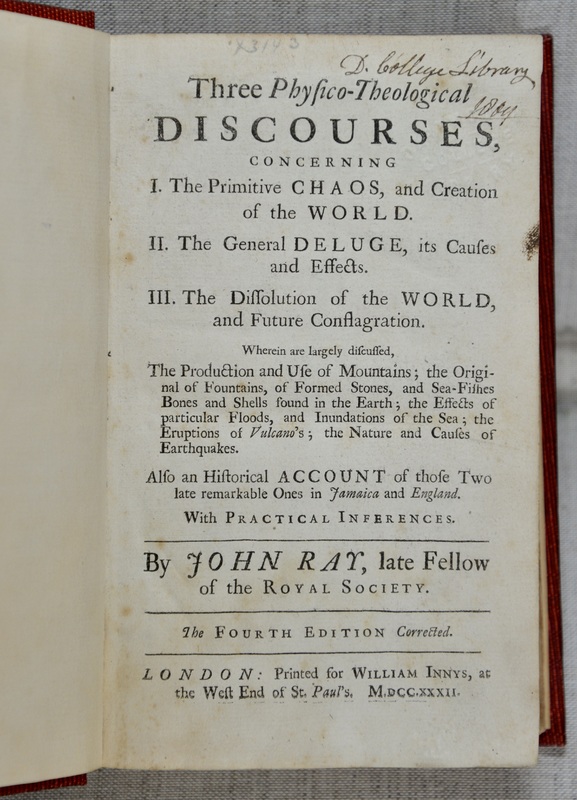

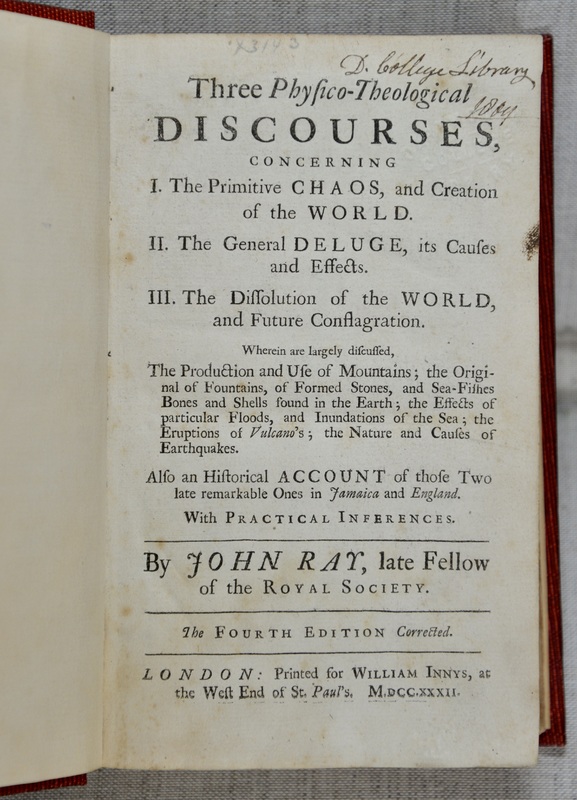

In this book, English naturalist John Ray elaborates on beliefs about the Great Flood from the Bible's Book of Genesis, during which God decides to reverse and redo creation by returning Earth to a state of watery chaos. While many 18th century natural historians and theologians used discovery of fossils (such as seashells in the Alps) as evidence of a global-scale flood, they did not see them as evidence of extinction. For many people during this time period, the idea of extinction was religiously troubling; it would suggest some flaw with God's divine plan at the beginning of the world. Additionally, belief that all life on Earth forms a Great Chain of Being—from ocean slime to angels—would make extinctions problematic breaks in its links.

-

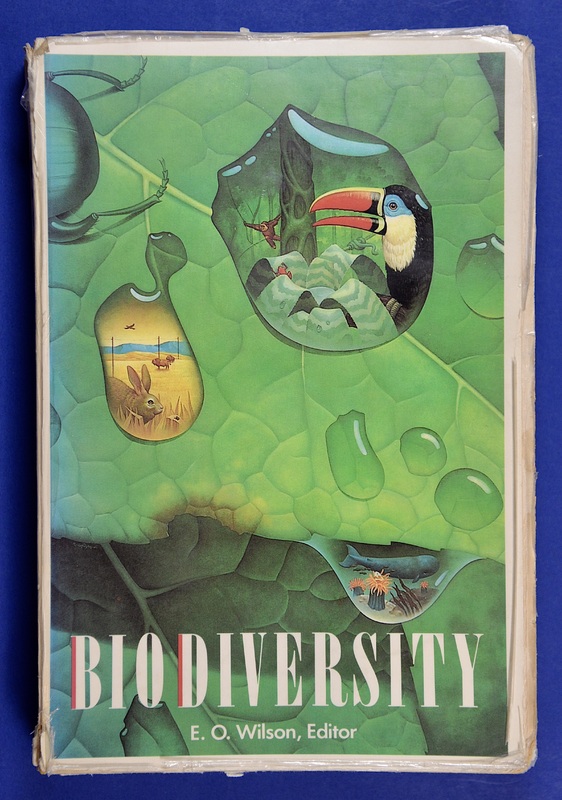

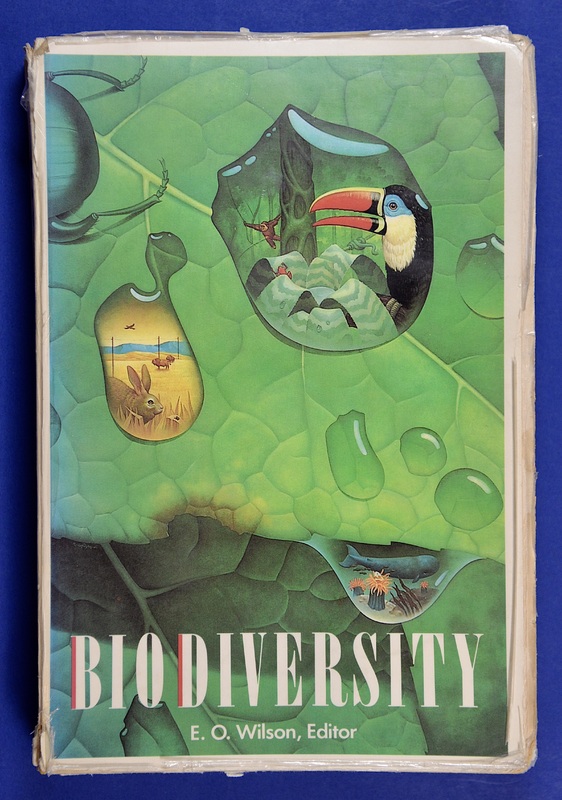

The 1980s witnessed a rise in concerns related to species conservation, due to growing awareness of the close link between economic development, deforestation, and extinction. This shift is evidenced by this publication by famed biologist, naturalist, and writer Edward O. Wilson which features the first appearance of the word “biodiversity” (defined as the variety of life in the world). Wilson writes, “The diversity of life forms, so numerous that we have yet to identify most of them, is the greatest wonder of this planet... The book before you offers an overall view of this biological diversity and carries the urgent warning that we are rapidly altering and destroying the environments that have fostered the diversity of life forms for more than a billion years.”

-

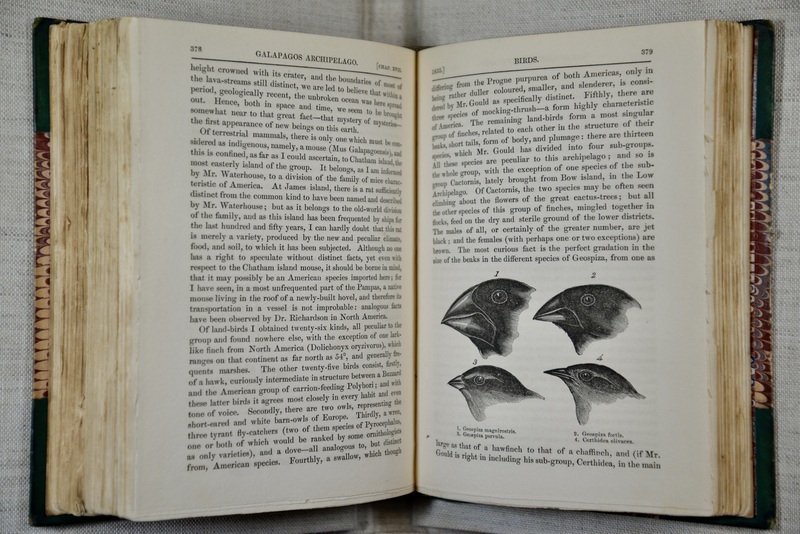

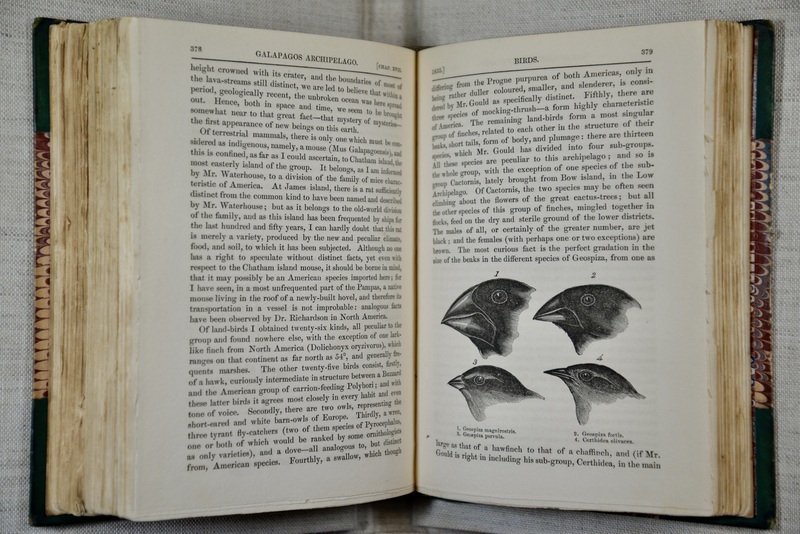

Charles Darwin’s (1809-1882) narrative of his voyage around the globe features the famous Galapagos finches whose beaks helped him develop his theory of evolution by natural selection. By observing the incredible variety of beak shapes among finch species, he postulated that the beak of an ancestral finch who had arrived at the remote island chain had adapted over time to equip the finches to acquire different food sources. Drawing on the diversity of Galapagos finches and other animals he encountered as examples of evolution by natural selection, Darwin’s theory fundamentally changed human understanding of species and how ecosystems change over time. Darwin posited that many species have died out as a result of competition between animals, and that this process had occurred gradually and continuously throughout the history of life. However, he neglected to clarify the role humans can play in driving species extinction, and believed that sudden disappearances of many species, or mass extinctions, did not actually occur.

-

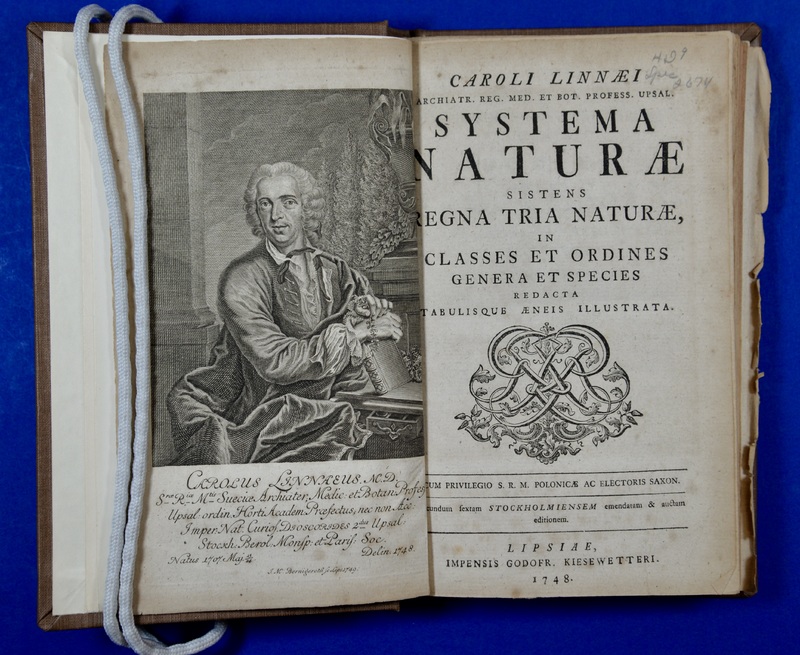

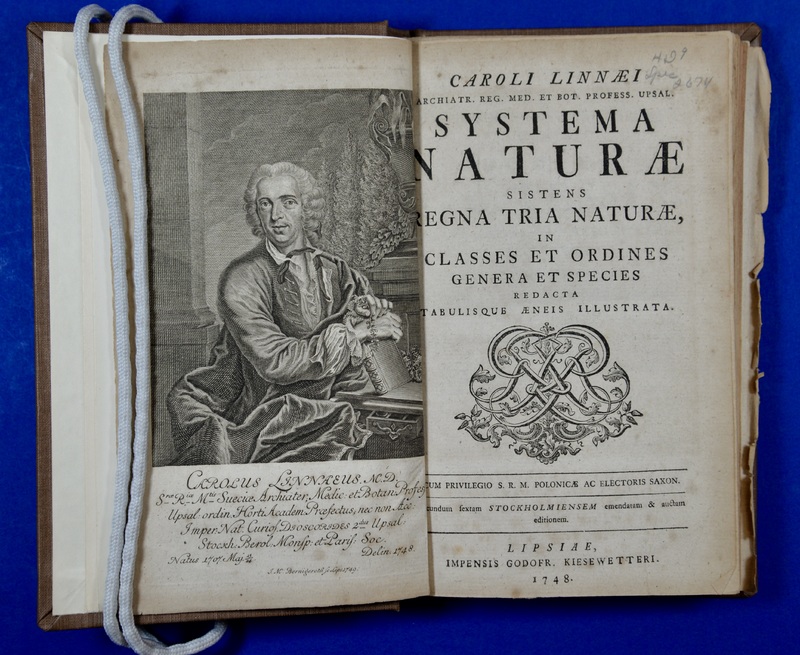

Swedish naturalist and explorer Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) revolutionized scientific understanding of the diversity of the natural world with the publication of Systema naturæ in 1735. Linneaus established binomial nomenclature, the system of formally classifying and naming organisms according to their genus and species. In contrast to earlier naming conventions that used long descriptive phrases, binomial names do not judge different species on their perceived quality or desirability. Serving as a means by which species could be universally addressed, this new hierarchical system allowed scientists to better conceptualize relationships between organisms.

-

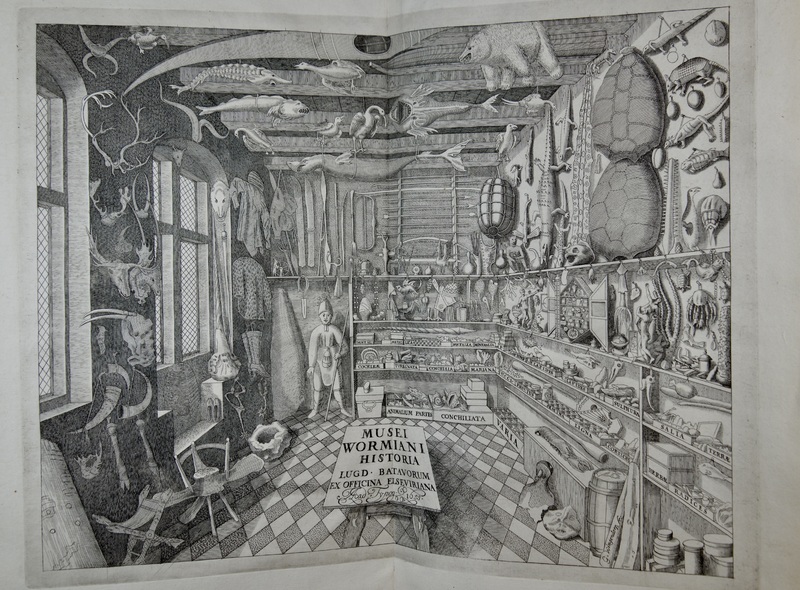

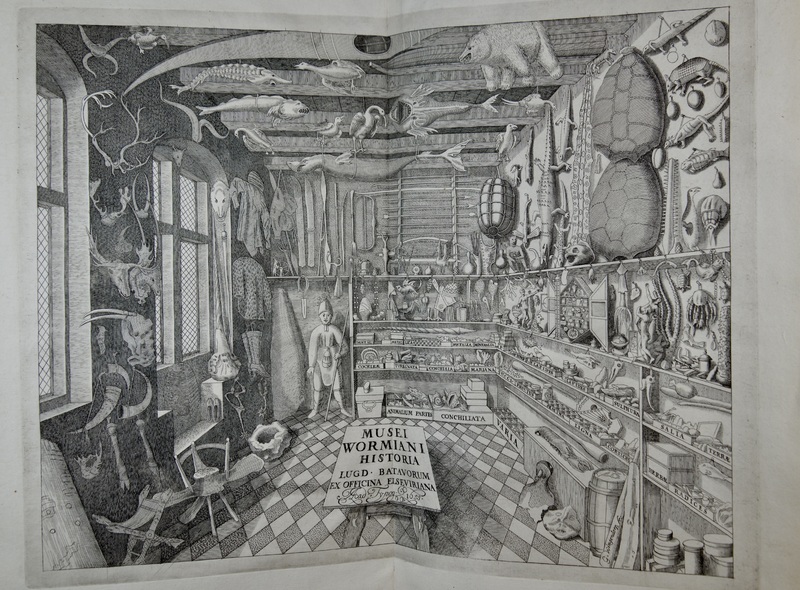

Natural historians like Ole Worm (1588 – 1654) sought to classify and understand the diversity of living organisms according to differences in their appearance in order to better understand God’s design in nature. This frontispiece depicts Worm's famous cabinet of curiosities, a massive collection of artifacts from across the globe, which included taxidermized animals, fossils, and weapons and tools owned by indigenous peoples. Look closely and you’ll notice several species now extinct, including the Great Auk, a seabird that Worm also owned as a pet.