-

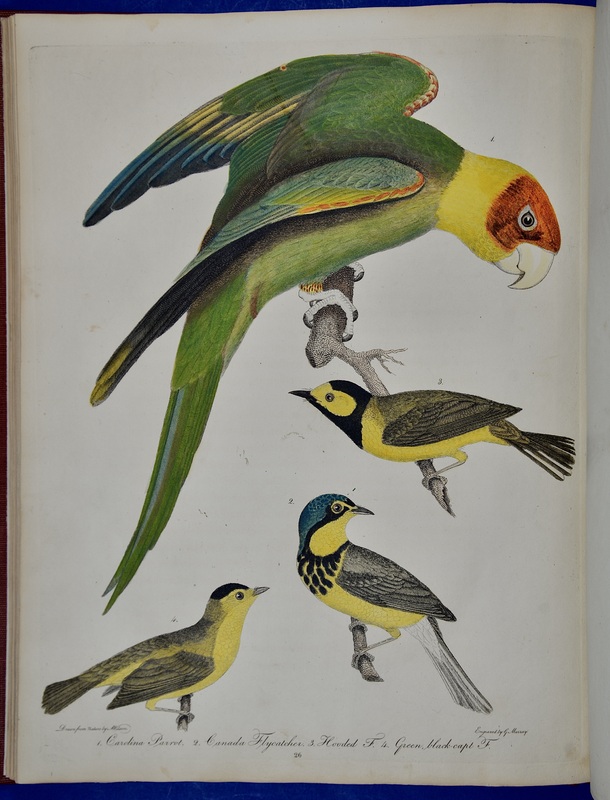

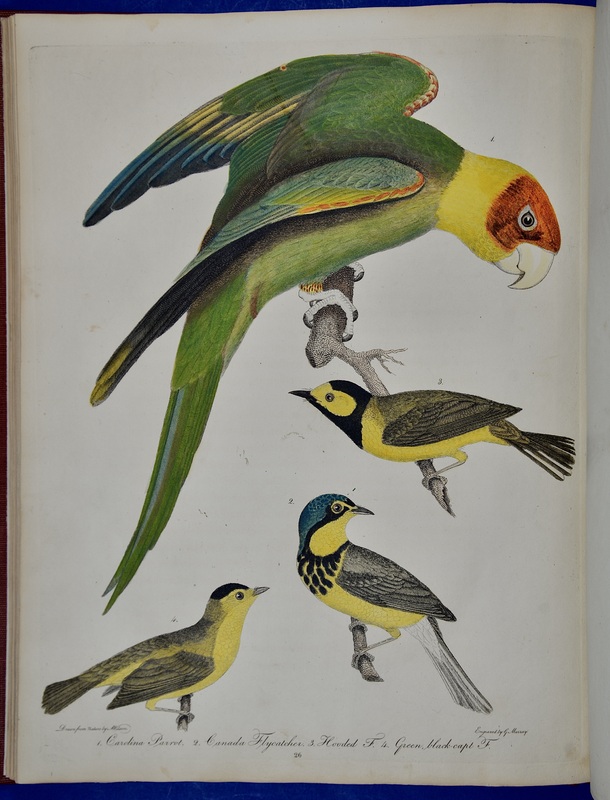

Alexander Wilson writes fondly of the Carolina Parakeet, America’s only parrot species, but he also discusses how they were a considerable nuisance to farmers. Their appetites lent them to being “destroyed in great numbers, for whilst busily engaged in plucking off the fruits or tearing the grain from the stacks, the husbandman approaches them with perfect ease, and commits great slaughter among them.” To make matters worse, the forests in which these birds lived were cleared in large swaths and their colorful feathers became popular decorations for women’s hats. The last Carolina Parakeet died in captivity at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1918. Aside from their bygone charms, Carolina Parakeets were important seed dispersers, meaning their disappearance negatively affected various seed-bearing plants.

-

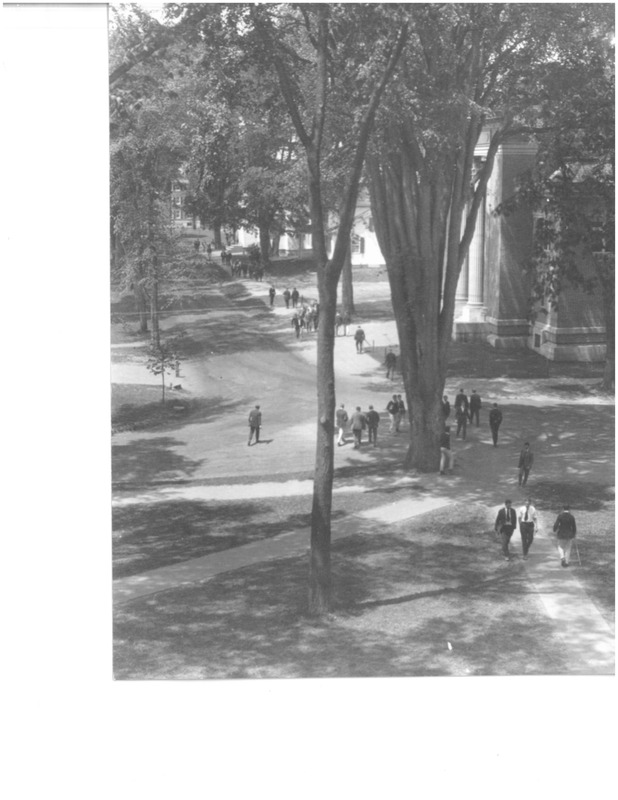

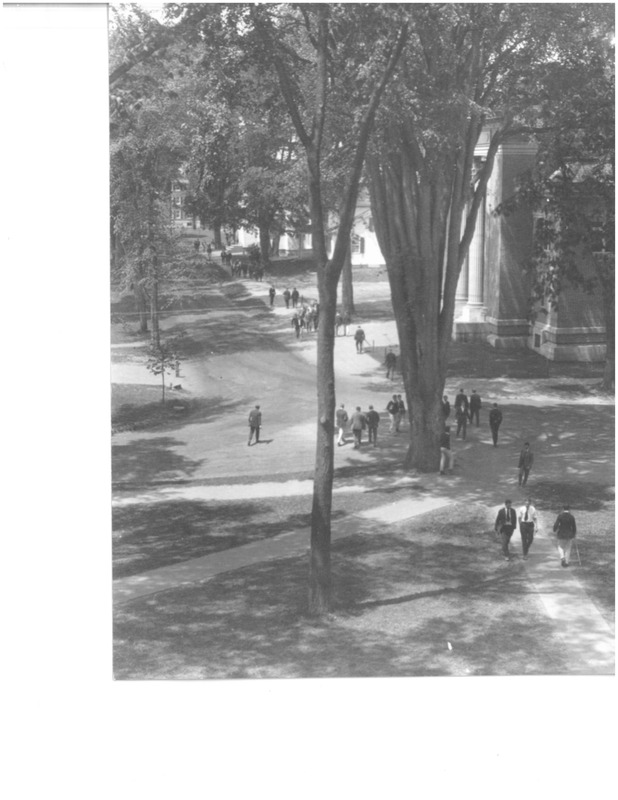

These photographs depict the large stands of American Elm trees that once towered above Dartmouth’s campus as well as their removal in the 1950s and 1960s when the trees began dying following the accidental introduction of Dutch Elm Disease (DED). Prior to the introduction of DED, American Elm trees were so plentiful around Hanover that Dartmouth was known as the “campus of a thousand elms.” As shown in these photographs, massive American elm trees once encircled the College Green, providing shade to students as they passed in front of Webster Hall (now home to Rauner Library). Until Dutch elm disease made its appearance, the life expectancy of an American elm was approximately 400 years (to see a photograph of a famous "old elm" which stood in front of famous Dartmouth alumni Daniel Webster's home in the late 1800s, see the fifth image in the attached PDF file). Today, American elms rarely live to reach 100 years old. Originally native to Asia, DED came to America in the 1920s when shipments of logs cut in the Netherlands brought with them fungus-carrying bark beetles. Since the arrival of these beetles, DED has devastated native elms without resistance to the disease. Of the estimated 77 million elm trees in North America in 1930, over 75% had been lost by 1989. While there may not be a thousand, Dartmouth's campus is still home to a few surviving elm trees, thanks to the help of periodic anti-fungal treatments and their isolation from one another; they stand as solemn testaments to the forests of years past. Today, the World Conservation Union estimates that globally, introduced invasive species like Dutch elm fungus may be as damaging on a global scale as habitat loss.

-

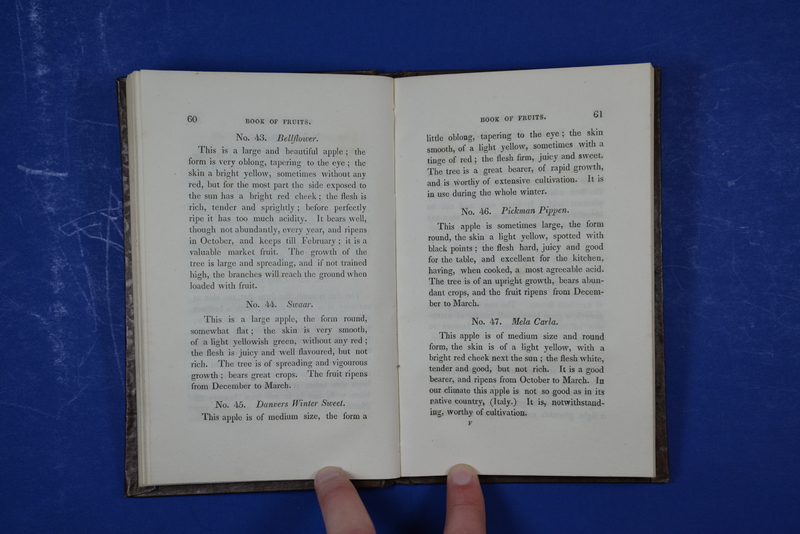

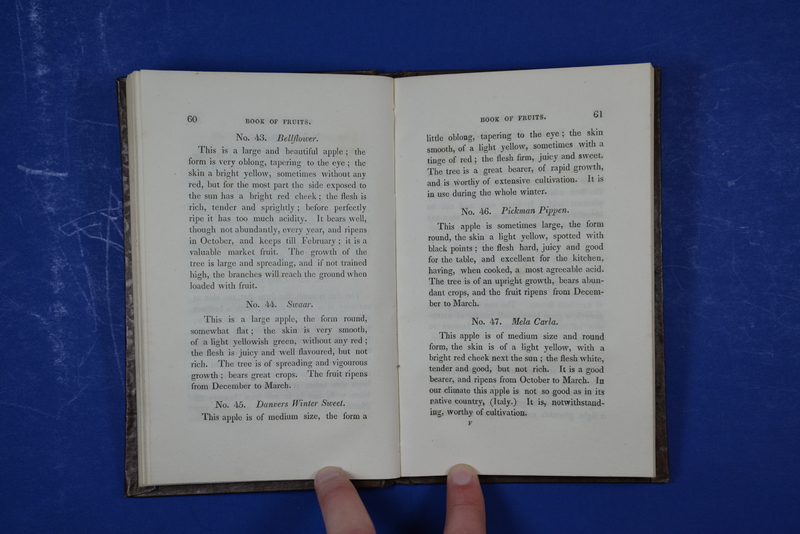

Not just animals face extinction. Humans have driven an estimated 600 plant species to extinction since the 1750s, along with thousands of locally cultivated varieties of staple food crops, from potatoes to apples. Once-popular New England apple varieties like the Pickman Pippen (see above) have since disappeared as higher-yielding and aesthetically uniform apple varieties used in industrial agriculture have come into favor. Scientists now express concern about our reliance on an ever-smaller number of plant varieties cultivated for human consumption, as this leaves large portions of our food supply vulnerable to be wiped out by a singular disease or pest, like during the Irish Potato Famine in the 1840s.

-

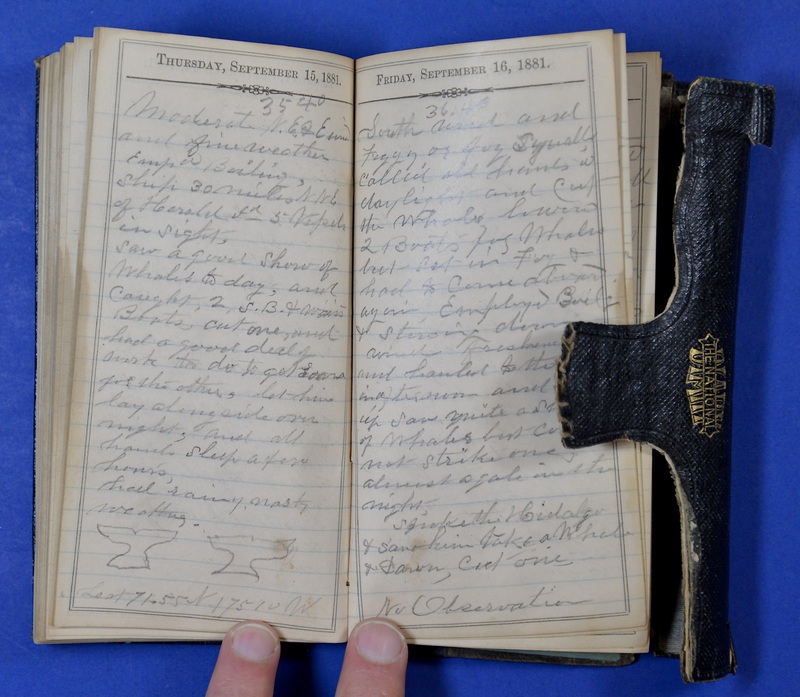

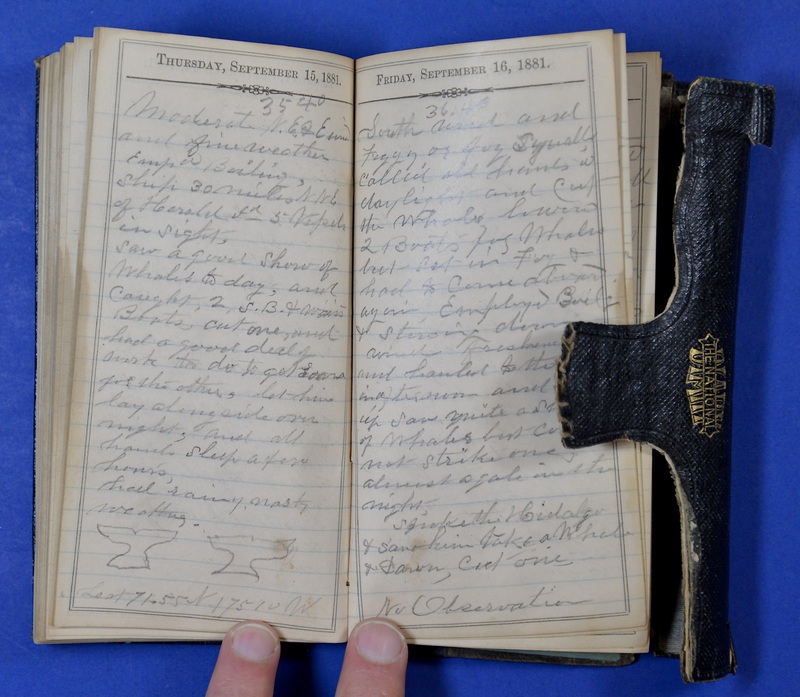

Leander Owen (1833-1911) was a ship captain and whaling master who travelled extensively through the Arctic during the peak of the Atlantic whaling fishery. Owen’s personal journal documents the first whaling trip ever made into the Arctic by a steam-powered vessel. The journal recounts the astonishing speed and efficiency with which sailors were killing Bowhead and North Atlantic right whales—both species that are endangered in their native habitats today. Each drawing of a whale’s tail in Owen’s journal denotes one animal successfully killed and “cut” (stripped of its blubber) within a given day.

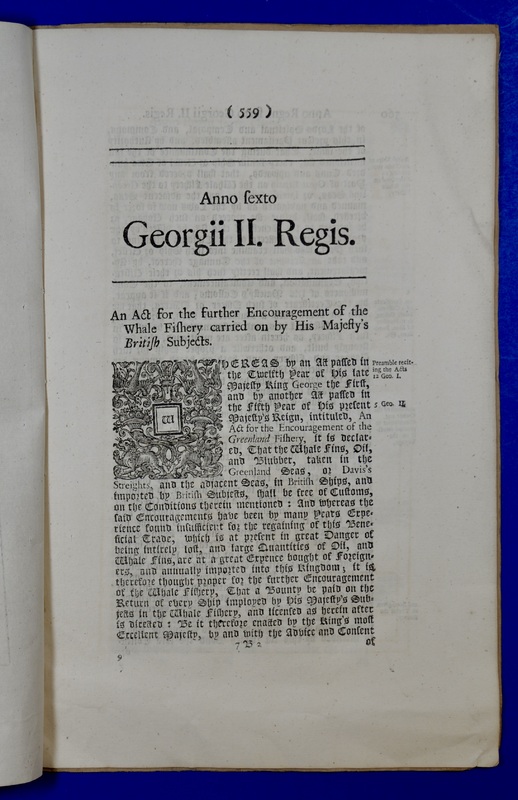

-

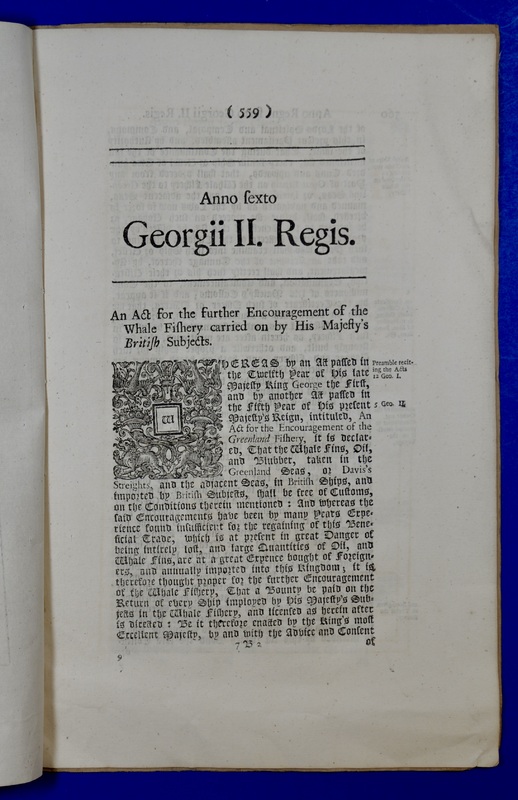

In hopes of encouraging more whaling expeditions around Greenland, British Parliament and King George II passed this Act. It provides for tax breaks and reduced costs for sailing supplies "on the condition that their firm purpose, and determined resolution... is to use the utmost endeavors of themselves and their ship's company to take whales, or other creatures living in the sea... and to import whales fins, oil, and blubber thereof into the Kingdom of Great Britain.” The Act was instituted out of fears that Great Britain was falling behind other European nations in its production of whale oil. In the race for economic dominance by imperialist powers such as Great Britain, such acts led to increased hunting pressure even as whale stocks began to decline.

-

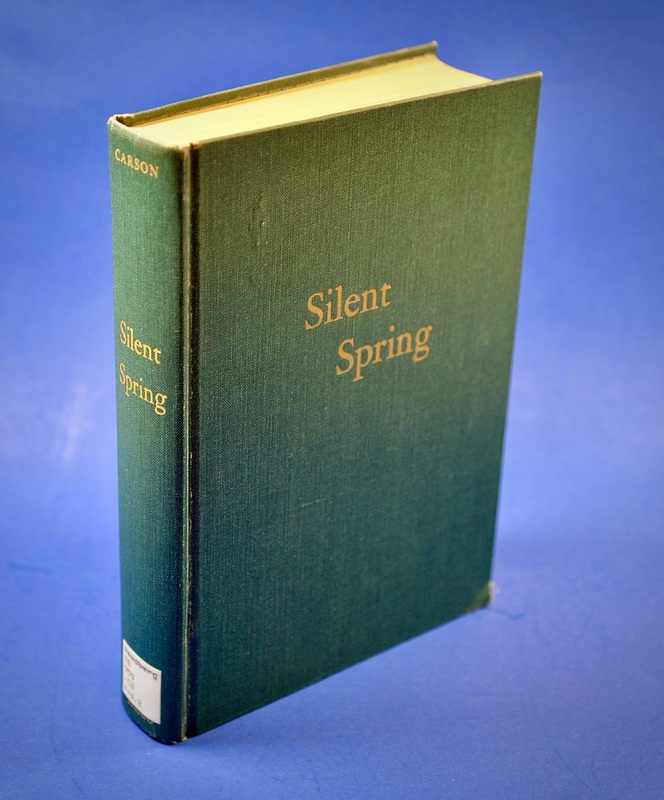

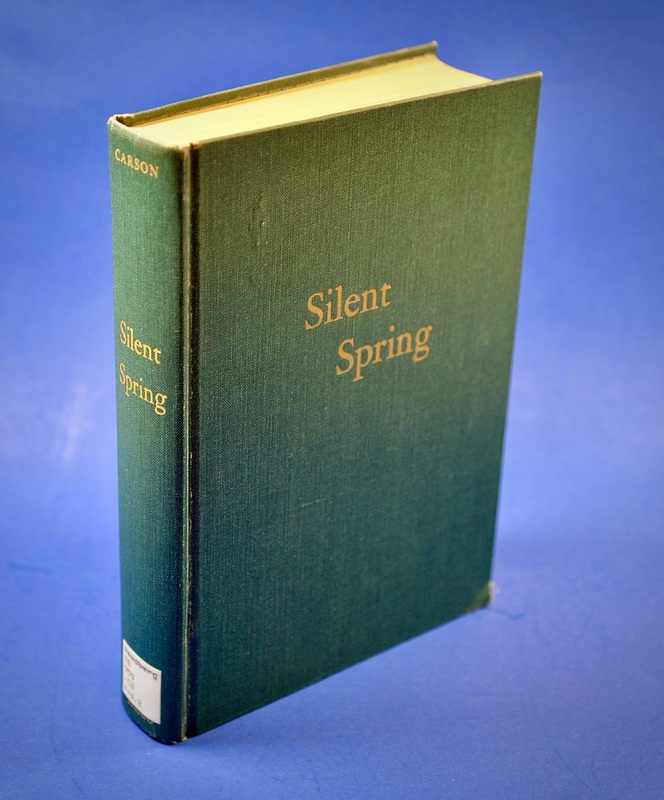

After the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962, the American public began to question their use of modern synthetic pesticides, such as dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane, or DDT. In the 30 years prior to being banned in 1972, a total of 1,350,000,000 pounds of DDT was sprayed across the United States. Carson reported that birds ingesting DDT tended to lay thin-shelled eggs that would break prematurely, resulting in population declines of more than 80 percent. Despite fierce opposition from chemical companies, Silent Spring ushered along numerous changes, including a reversal in United States pesticide policy, a nationwide ban on DDT in agriculture, and the eventual establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency by those inspired by the text. The book condoned short-sighted tampering with the environment that was pervasive during the Cold War, challenging farmers, companies, and the U.S. government to consider the long-term side effects of their actions. Without Silent Spring, the ban on DDT and ensuing protections, the bald eagle and dozens of other bird species would have likely disappeared from the continental U.S.

-

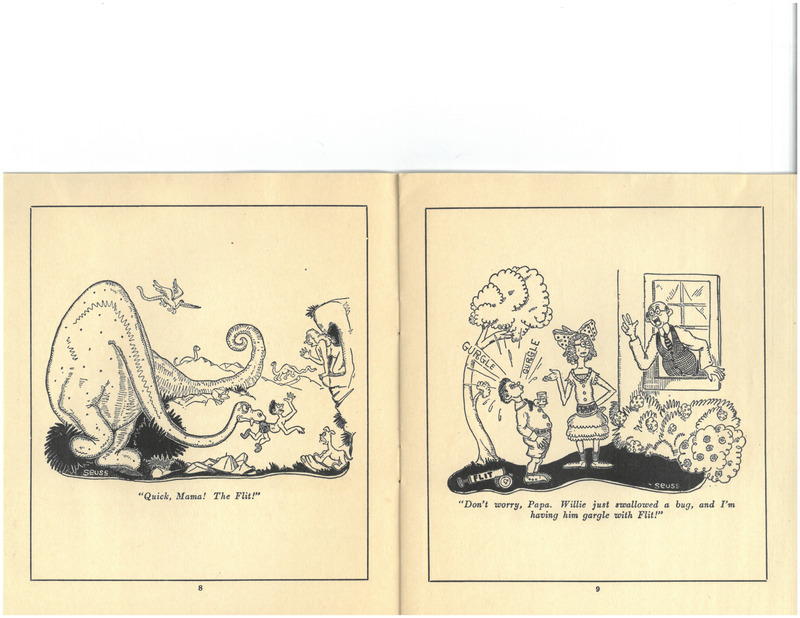

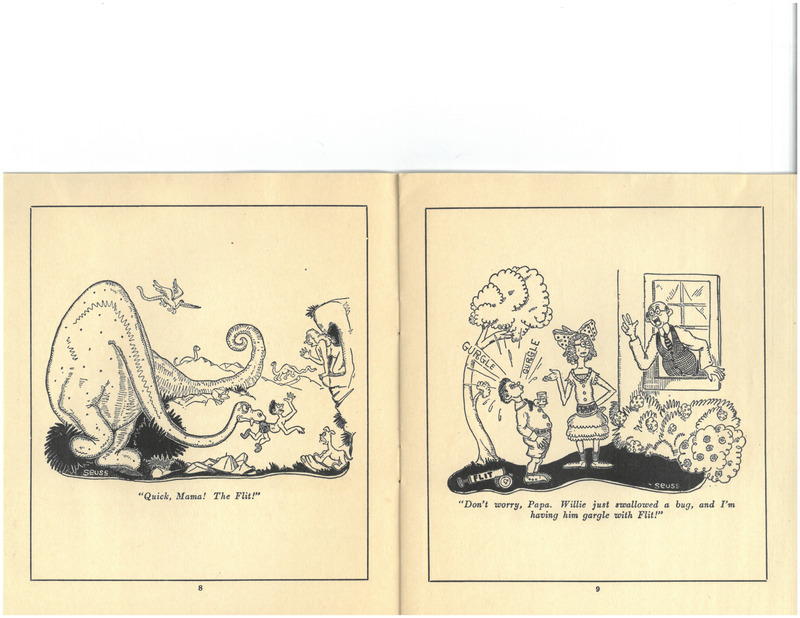

Long before his success as Dr. Seuss, Theodore Geisel (Dartmouth Class of 1925), designed advertisements for Flit, Standard Oil Company’s wildly popular spray-pump insecticide which later contained DDT. Over the course of 17 years, Geisel’s humorous advertisements helped make Flit a household name throughout the 1930s and 1940s. At the time, liberal spraying of pesticides around people, animals, and crops was highly encouraged with little regard to potential environmental impacts.

-

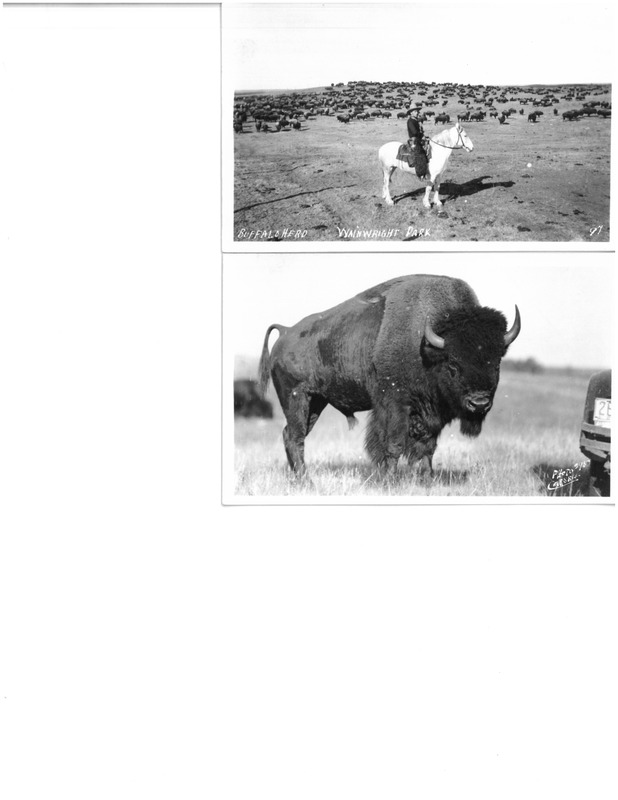

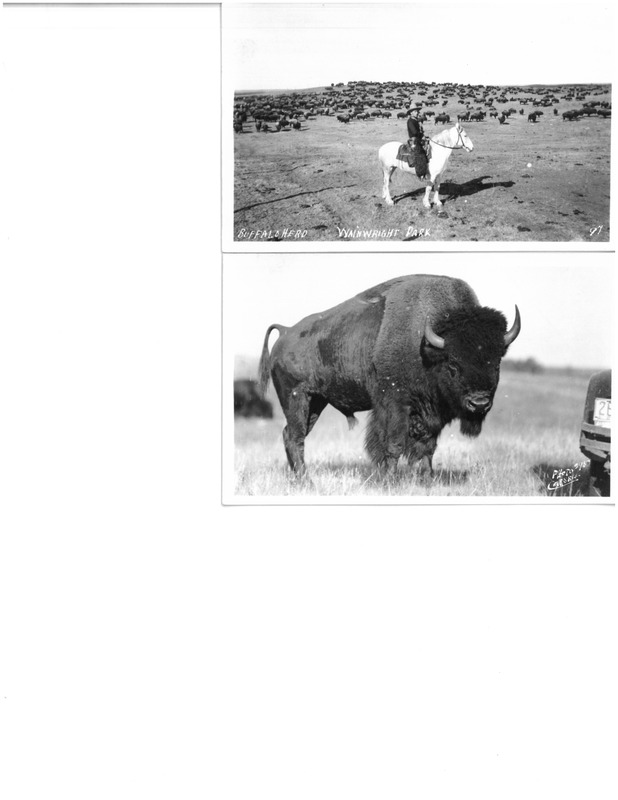

Herds of bison roamed what is now Banff National Park in Alberta, Canada for 10,000 years until nearly driven to extinction by human activity prior to the park's creation in 1885. These photographs depict herds of plains bison in Wainwright Buffalo Park, Canada, established in 1909 to regenerate dangerously low populations of bison (and to produce beef as the photo captions indicate). In December of 2019, Parks Canada announced the release of a small herd of plains bison in Banff, over 140 years after local populations were hunted to extinction.

-

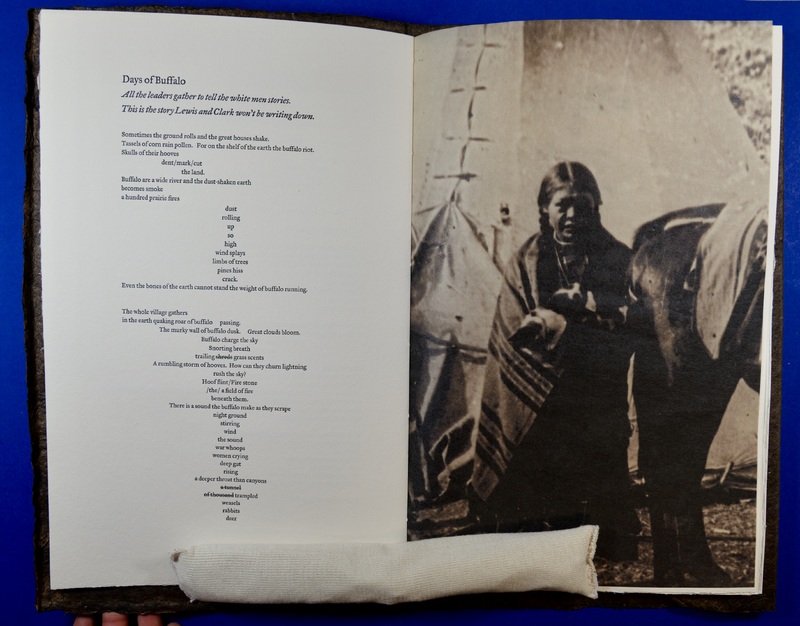

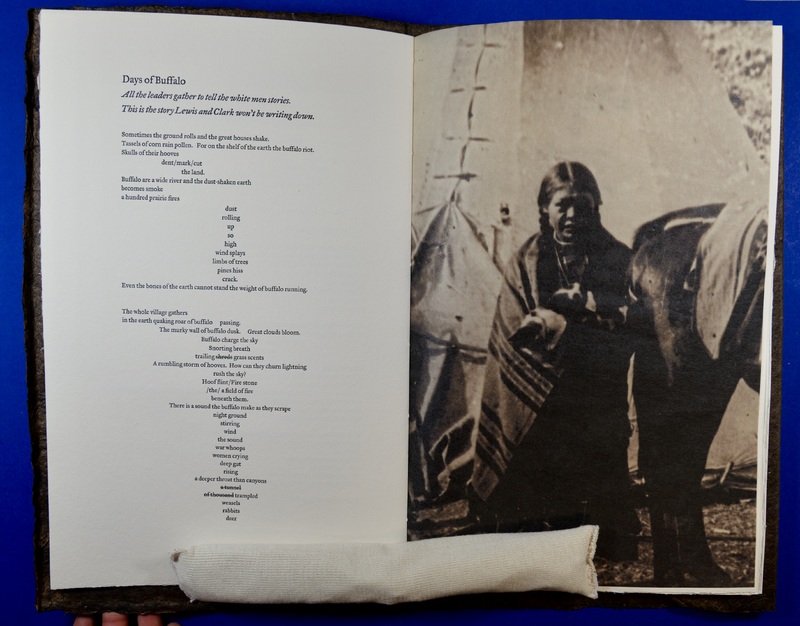

Debra Magpie Earling, a member of the Confederated Shalish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation, created this artist book during the bicentennial of the Lewis and Clark expedition to represent the hardships brought upon Native American cultures by colonialism. The cultural importance of the plains bison and the effects of its near extermination from the American West is reflected in both Earling’s poetry and the materials used to construct the book—it’s printed on smoked buffalo rawhide cover paper with trade beads and rifle shell cartridges adorning the spine. Earling writes, “Only a few photographs document the extermination of the bison and the hunter’s struggles against starvation. Instead, as if to marginalize the dying cultures, countless images survive that depict the arrival of the mining spectator, soldier, cowboy… all that followed to give us a thorough and close-up look at the noble savage-free territory of post-bison civilization.”

-

These walrus ivory carvings owned by Alex Magtoya were produced by native Inupiat people of the Arctic Ocean and Bering Sea regions. Indigenous communities of the Arctic have hunted walrus (among other sea mammals including seals and whales) as sources of food for hundreds of years, utilizing their skins, bones, and tusks for clothing, tools, and crafts. Walrus populations plummeted around the Arctic by the early 20th-century following the arrival of Europeans, only to rebound when limits were placed on commercial hunts. Today, walruses, polar bears, and many other Arctic animals face an even-deadlier threat - global climate change.