CASE 3: EXTINCTION - WHAT CAN WE DO ABOUT IT?

Scientists contend that we’re heading toward what would be the sixth mass extinction in the history of life on Earth. There’s no doubt humanity has increased the rate of extinction by several orders of magnitude, but the extent to which ecosystems will be altered in the 21st century is still yet to be determined. Amid new challenges presented by global climate change and rapid globalization, the future is more uncertain than ever. One thing is clear though: collectively, we have a say in the matter - we can proceed with “business as usual”, or we can reevaluate our perceptions of and relationship with the natural world in an effort to save more species from extirpation. The laws we enact, the value we place on plants and animals, the way we produce and consume food, the products we buy… all these actions collectively affect how many species will go extinct. Although a 2019 United Nations report presented grim findings that upwards of one million species “are now threatened with species extinction, many within decades”, scientists contend that many organisms can still be saved, as long as we commit to changing.

Environmental success stories of the past - from changes in attitudes surrounding gray wolves to the passage of the Migratory Bird Act - serve as examples of what we can do to help. In each instance, humans exhibited a capability or a willingness to change behaviors and/or structures in order to protect and preserve a unique part of the natural world. If we continue to learn from past successes and take collective action to implement changes in the present, we can create what Wilson calls “a planet for all species.”

Case 3 Items : What can we do?

-

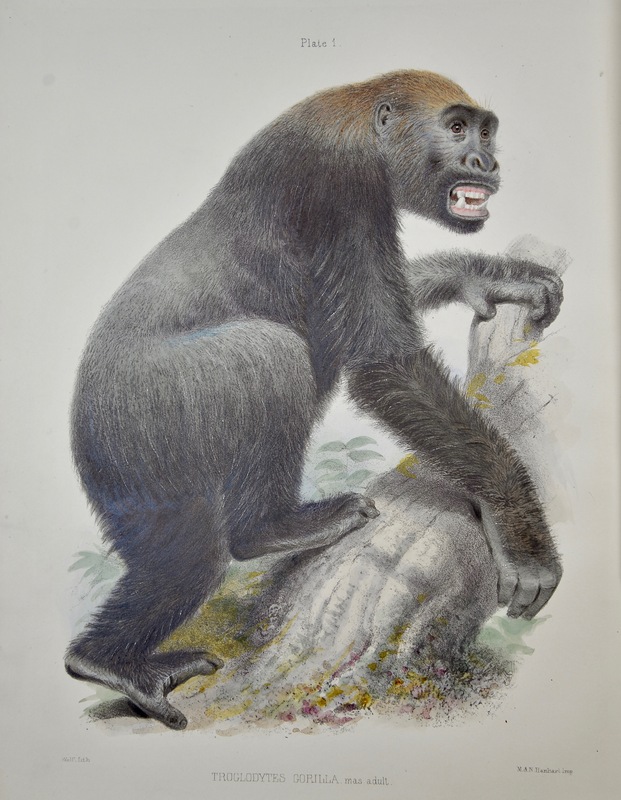

Memoir on the gorilla : (Troglodytes gorilla, Savage) English taxonomist and paleontologist Richard Owen (1804-1892) published Memoir on the Gorilla only nine years after Paul Belloni Du Chaillu became the first European to confirm the existence of gorillas in the wild during his expedition to Gabon in 1856. Owens – famous for having taught natural history to Queen Victoria’s children, his quarrels with famed naturalist Charles Darwin, and for naming a new taxon of large extinct reptiles – Dinosauria – in 1842 – wrote the first complete anatomical description of gorillas using several preserved specimens collected by Du Chaillu. Despite his anatomical accuracy, Owen’s anti-Darwinian views led him to erroneously state that gorillas lack certain parts of the brain that humans have, specifically a structure called the hippocampus minor, citing this as evidence that humans could not possibly be related to apes. Owens also erred in his account of the gorilla’s behaviors, reflecting the fear and misunderstanding of great apes that later led to their frequently being killed by thrill-seeking hunters and poachers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. On page 35, Owens writes “Lacerations of the abdomen and laying bare of the intestines of a hunter are described as the effects of a blow of… the Gorilla… Mr. Du Chaillu also adduces the testimony of the natives, that, when stealing through the gloomy shades of the tropical forest, they become sometimes aware of the proximity of one of these frightfully formidable Apes by the sudden disappearance of one of their companions, who is hoisted up into the tree, uttering perhaps, a short choking cry. In a few minutes he falls to the ground a strangled corpse.” Even as primatologists later disproved these harmful perceptions of gorillas, gorilla numbers across Africa declined dramatically over the last century due to destruction of habitat from agricultural expansion and timber harvest, poaching, war and political unrest, and human disturbance. Today, all gorilla subspecies are classified as “Endangered” according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (ICUN) criteria. However, dedicated conservation initiatives have ensured that gorilla numbers are now slowly increasing. Innovative new conservation ideas, including remotely monitoring gorilla movement and spreading awareness of the dangers of consuming bushmeat have shown some success in slowing gorilla population declines. In fact, the World Wildlife Fund recently announced that mountain gorilla numbers have increased to above 1,000 individuals for the first time in decades due to conservation efforts. Traditional protected areas are still one of the main conservation strategies to address threats such as hunting and habitat loss, however new tactics including working directly with logging companies and local communities to regulate the bush meat trade have also helped to reduce hunting pressure. If gorillas are to be conserved into the future, a combination of national parks, reducing human conflict, and working with local farmers and loggers will all be essential tools for maintaining viable populations.

Memoir on the gorilla : (Troglodytes gorilla, Savage) English taxonomist and paleontologist Richard Owen (1804-1892) published Memoir on the Gorilla only nine years after Paul Belloni Du Chaillu became the first European to confirm the existence of gorillas in the wild during his expedition to Gabon in 1856. Owens – famous for having taught natural history to Queen Victoria’s children, his quarrels with famed naturalist Charles Darwin, and for naming a new taxon of large extinct reptiles – Dinosauria – in 1842 – wrote the first complete anatomical description of gorillas using several preserved specimens collected by Du Chaillu. Despite his anatomical accuracy, Owen’s anti-Darwinian views led him to erroneously state that gorillas lack certain parts of the brain that humans have, specifically a structure called the hippocampus minor, citing this as evidence that humans could not possibly be related to apes. Owens also erred in his account of the gorilla’s behaviors, reflecting the fear and misunderstanding of great apes that later led to their frequently being killed by thrill-seeking hunters and poachers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. On page 35, Owens writes “Lacerations of the abdomen and laying bare of the intestines of a hunter are described as the effects of a blow of… the Gorilla… Mr. Du Chaillu also adduces the testimony of the natives, that, when stealing through the gloomy shades of the tropical forest, they become sometimes aware of the proximity of one of these frightfully formidable Apes by the sudden disappearance of one of their companions, who is hoisted up into the tree, uttering perhaps, a short choking cry. In a few minutes he falls to the ground a strangled corpse.” Even as primatologists later disproved these harmful perceptions of gorillas, gorilla numbers across Africa declined dramatically over the last century due to destruction of habitat from agricultural expansion and timber harvest, poaching, war and political unrest, and human disturbance. Today, all gorilla subspecies are classified as “Endangered” according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (ICUN) criteria. However, dedicated conservation initiatives have ensured that gorilla numbers are now slowly increasing. Innovative new conservation ideas, including remotely monitoring gorilla movement and spreading awareness of the dangers of consuming bushmeat have shown some success in slowing gorilla population declines. In fact, the World Wildlife Fund recently announced that mountain gorilla numbers have increased to above 1,000 individuals for the first time in decades due to conservation efforts. Traditional protected areas are still one of the main conservation strategies to address threats such as hunting and habitat loss, however new tactics including working directly with logging companies and local communities to regulate the bush meat trade have also helped to reduce hunting pressure. If gorillas are to be conserved into the future, a combination of national parks, reducing human conflict, and working with local farmers and loggers will all be essential tools for maintaining viable populations. -

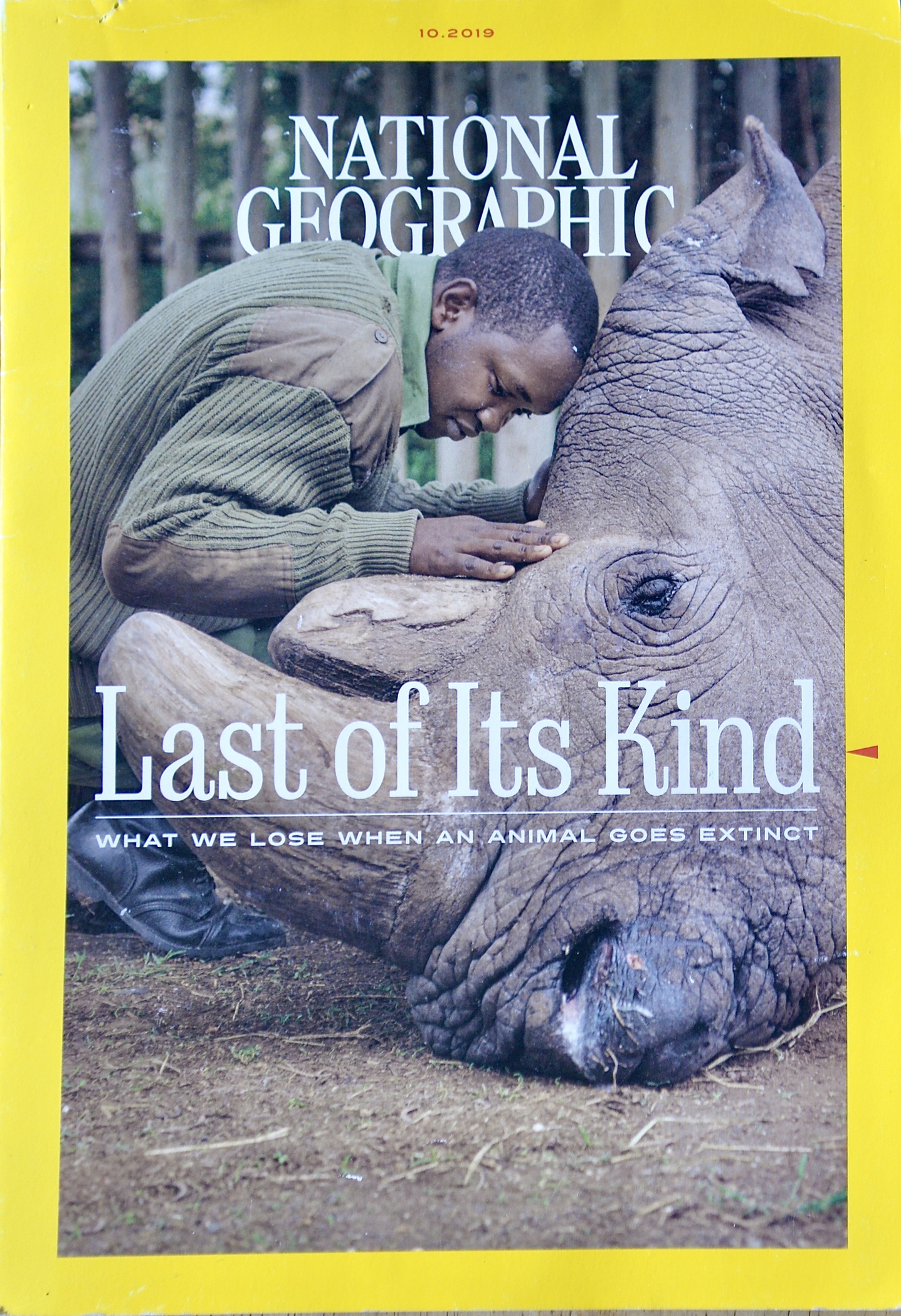

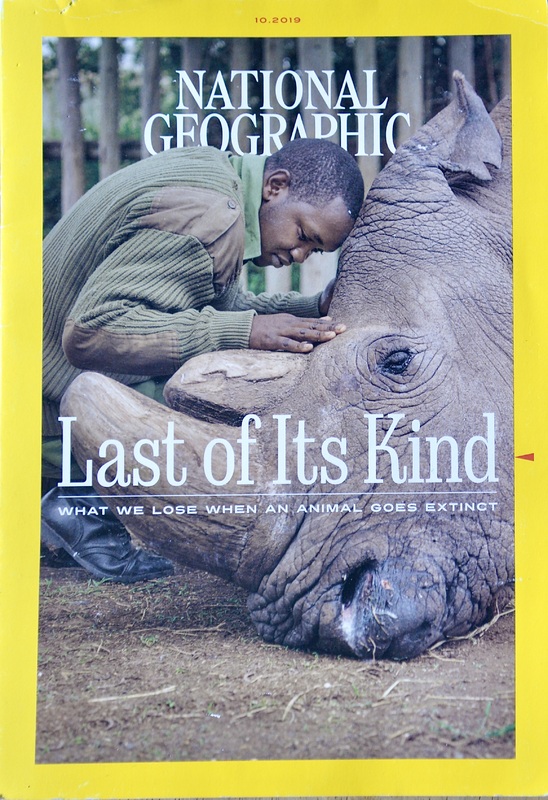

National Geographic Magazine, Oct 2019 The October 2019 cover of National Geographic depicts Joseph Wachira, a keeper at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya as he says goodbye to the last male northern white rhinoceros who died in 2018. This poignant image struck a chord with many readers, landing it a spot in the magazine’s “best photographs of the decade.” According to National Geographic photographer Joel Satore, photos like these are important to sensitizing viewers, “because extinction takes place so frequently now, it’s possible to become inured to it.” A recent UN report found that one million species “are now threatened with extinction, many within decades,” spurring National Geographic to dedicate their October edition to asking, “what do we lose when we lose a species?”

National Geographic Magazine, Oct 2019 The October 2019 cover of National Geographic depicts Joseph Wachira, a keeper at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya as he says goodbye to the last male northern white rhinoceros who died in 2018. This poignant image struck a chord with many readers, landing it a spot in the magazine’s “best photographs of the decade.” According to National Geographic photographer Joel Satore, photos like these are important to sensitizing viewers, “because extinction takes place so frequently now, it’s possible to become inured to it.” A recent UN report found that one million species “are now threatened with extinction, many within decades,” spurring National Geographic to dedicate their October edition to asking, “what do we lose when we lose a species?” -

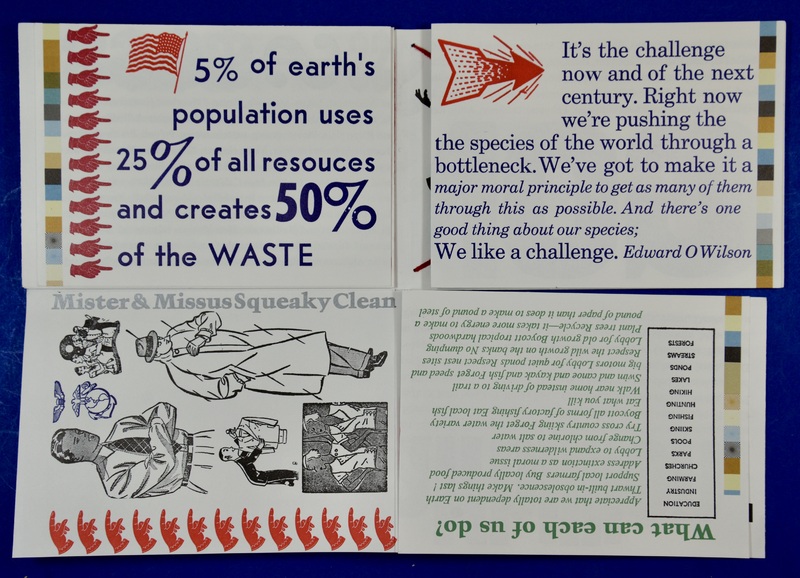

Volumes (of Vulnerability) Volumes (of Vulnerability) highlights the contemporary causes of what the authors call “a sixth mass extinction driven by human expansion,” such as consumerism and global climate change. In so doing, it challenges viewers to consider what each of us can do to combat these man-made threats to plants and animals. While Johanknecht and Meynell note that slowing species loss will prove difficult, they evoke conservationist E. O. Wilson’s sentiment that “(humans) like a challenge.”

Volumes (of Vulnerability) Volumes (of Vulnerability) highlights the contemporary causes of what the authors call “a sixth mass extinction driven by human expansion,” such as consumerism and global climate change. In so doing, it challenges viewers to consider what each of us can do to combat these man-made threats to plants and animals. While Johanknecht and Meynell note that slowing species loss will prove difficult, they evoke conservationist E. O. Wilson’s sentiment that “(humans) like a challenge.” -

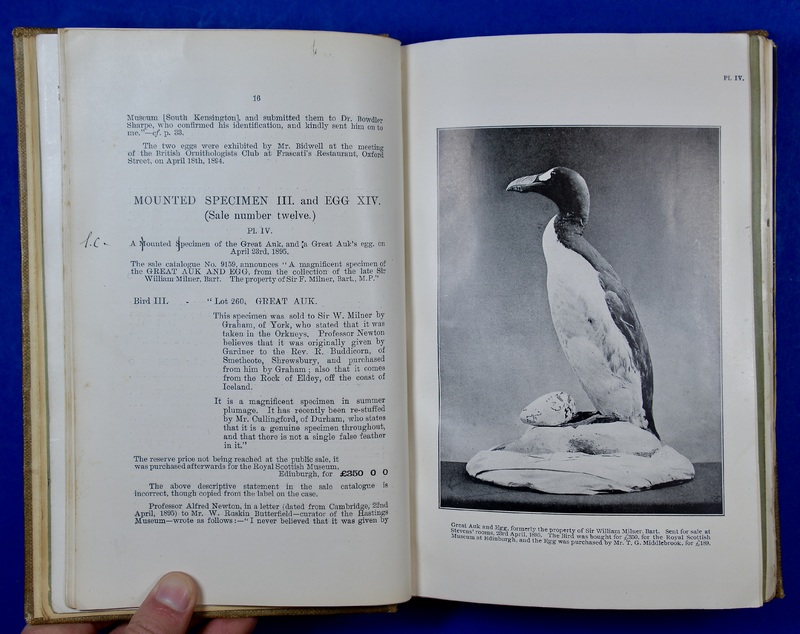

The Great Auk: Sales of Birds and Eggs by Public Auction in Great Britain, 1806-1910 The Great Auk was once a seabird native to the North Atlantic. Hunted since prehistoric times, its numbers dwindled rapidly as sailors learned to hunt the birds along the sea cliffs of Iceland and Nova Scotia. To make matters worse, the last colony of Auks was nearly destroyed by a volcanic eruption off of Iceland in 1830, after which only 60 birds remained. Museums and collectors began to worry that they might disappear and paid to have 48 of the surviving birds killed for specimens, ironically dooming the species to extinction. The last two Auks in the world were killed to add to a businessman’s bird collection in 1844. The extinction of the Auk should be a sobering tale for us today. Will we wait until more species become specimens and collectables, or will we strive to protect species in their natural habitats before it’s too late?

The Great Auk: Sales of Birds and Eggs by Public Auction in Great Britain, 1806-1910 The Great Auk was once a seabird native to the North Atlantic. Hunted since prehistoric times, its numbers dwindled rapidly as sailors learned to hunt the birds along the sea cliffs of Iceland and Nova Scotia. To make matters worse, the last colony of Auks was nearly destroyed by a volcanic eruption off of Iceland in 1830, after which only 60 birds remained. Museums and collectors began to worry that they might disappear and paid to have 48 of the surviving birds killed for specimens, ironically dooming the species to extinction. The last two Auks in the world were killed to add to a businessman’s bird collection in 1844. The extinction of the Auk should be a sobering tale for us today. Will we wait until more species become specimens and collectables, or will we strive to protect species in their natural habitats before it’s too late? -

The Return of the Wolf to Yellowstone Wolf population recovery was made possible by the monumental declaration of protection for the gray wolf under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in 1974. Reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park and Idaho in 1995 further enabled this recovery after years of political battles and grassroots efforts to win support from local ranchers. Since the wolf’s return, scientists have documented a myriad of environmental benefits, including increases in beaver, brook trout, aspen, and willow tree populations. Elk and deer populations overgraze low-lying shrub habitats, altering river flows and habitats crucial to other animals if not checked by wolves. Gray wolves now inhabit 13 states, but their status as an endangered species remains in limbo at both the federal and state levels, threatening the potential progress enabled by their protection.

The Return of the Wolf to Yellowstone Wolf population recovery was made possible by the monumental declaration of protection for the gray wolf under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in 1974. Reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park and Idaho in 1995 further enabled this recovery after years of political battles and grassroots efforts to win support from local ranchers. Since the wolf’s return, scientists have documented a myriad of environmental benefits, including increases in beaver, brook trout, aspen, and willow tree populations. Elk and deer populations overgraze low-lying shrub habitats, altering river flows and habitats crucial to other animals if not checked by wolves. Gray wolves now inhabit 13 states, but their status as an endangered species remains in limbo at both the federal and state levels, threatening the potential progress enabled by their protection. -

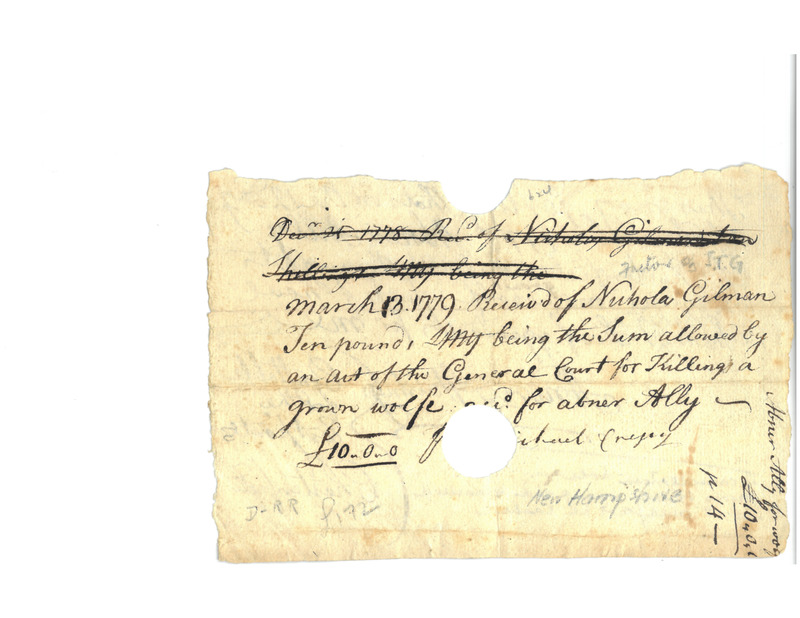

New Hampshire Wolf Bounty Receipt, 12 December 1778 "March 13, 1779 - Receiv'd of Nicholas Gilman Ten pounds, being the Sum allowed by an act of the General Court for killing a grown wolfe £10.00 and for Abner Ally…This may certify that on the 12 day of December 1778, Abner Ally of Chesterfield killed + brought in to me one grown Woolf which I have taken there + disfiggered it for me" Wolf bounties paid to Gilman and Ally were worth a considerable sum; £10 in 1800 had the purchasing power of £816.00 in 2018. The hole punched in this document indicates the bounty was paid and cancelled to assure it was not cashed twice. Colonial and federal governments encouraged the extermination of wolves in the U.S. for over 300 years, as Europeans viewed them as bloodthirsty killers and threats to livestock.

New Hampshire Wolf Bounty Receipt, 12 December 1778 "March 13, 1779 - Receiv'd of Nicholas Gilman Ten pounds, being the Sum allowed by an act of the General Court for killing a grown wolfe £10.00 and for Abner Ally…This may certify that on the 12 day of December 1778, Abner Ally of Chesterfield killed + brought in to me one grown Woolf which I have taken there + disfiggered it for me" Wolf bounties paid to Gilman and Ally were worth a considerable sum; £10 in 1800 had the purchasing power of £816.00 in 2018. The hole punched in this document indicates the bounty was paid and cancelled to assure it was not cashed twice. Colonial and federal governments encouraged the extermination of wolves in the U.S. for over 300 years, as Europeans viewed them as bloodthirsty killers and threats to livestock. -

Our National Parks John Muir, the “Father of the National Parks,” was an influential Scottish-American naturalist, author, environmental philosopher, and early advocate for the preservation of wilderness. His letters, essays, and books have been read by millions interested in his experiences in nature. Thanks to Muir’s activism, Yosemite Valley, Sequoia National Park, and many other wilderness areas have been preserved. The Sierra Club, which he co-founded, remains a prominent American conservation organization. In Our National Parks, Muir extolled the beauty, grandeur, and importance of Yosemite, Sequoia, Yellowstone, and other National Parks to the American public and urged continued preservation of these natural areas as sanctuaries for both humans and wildlife.

Our National Parks John Muir, the “Father of the National Parks,” was an influential Scottish-American naturalist, author, environmental philosopher, and early advocate for the preservation of wilderness. His letters, essays, and books have been read by millions interested in his experiences in nature. Thanks to Muir’s activism, Yosemite Valley, Sequoia National Park, and many other wilderness areas have been preserved. The Sierra Club, which he co-founded, remains a prominent American conservation organization. In Our National Parks, Muir extolled the beauty, grandeur, and importance of Yosemite, Sequoia, Yellowstone, and other National Parks to the American public and urged continued preservation of these natural areas as sanctuaries for both humans and wildlife. -

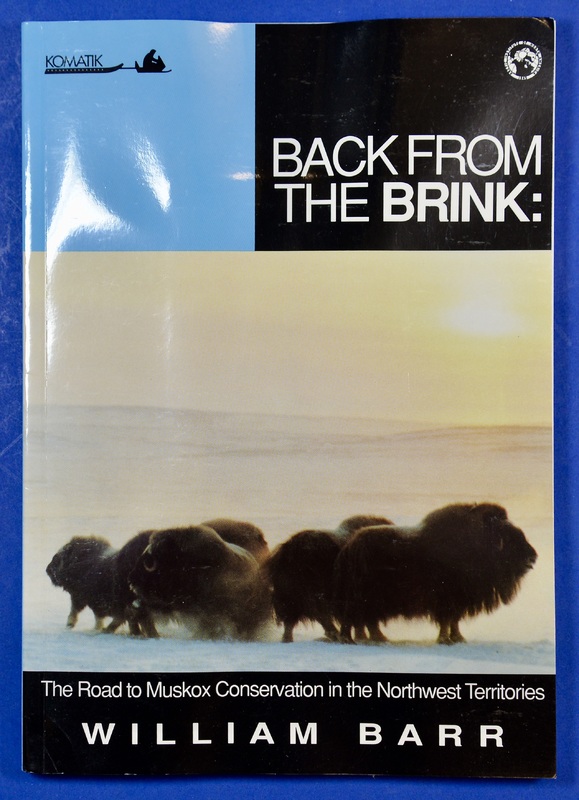

Back from the Brink: the Road to Muskox Conservation Muskoxen hides were primarily used for sleigh and carriage robes in Europe between 1860-1916, as substitutes for rapidly disappearing bison hides. According to Barr’s research, the Hudson Bay Company traded 17,485 muskoxen hides during the trade peak in the 1860s-1890s. After the number of muskoxen in the Northwest Territories reached a critically low level around 1915, legislation was passed in 1917 banning commercial hide sales. Thanks to these legal protections and subsequent management by local Inupiaq communities, muskoxen numbers have risen dramatically. Today the animals have recolonized practically their entire historic range.

Back from the Brink: the Road to Muskox Conservation Muskoxen hides were primarily used for sleigh and carriage robes in Europe between 1860-1916, as substitutes for rapidly disappearing bison hides. According to Barr’s research, the Hudson Bay Company traded 17,485 muskoxen hides during the trade peak in the 1860s-1890s. After the number of muskoxen in the Northwest Territories reached a critically low level around 1915, legislation was passed in 1917 banning commercial hide sales. Thanks to these legal protections and subsequent management by local Inupiaq communities, muskoxen numbers have risen dramatically. Today the animals have recolonized practically their entire historic range. -

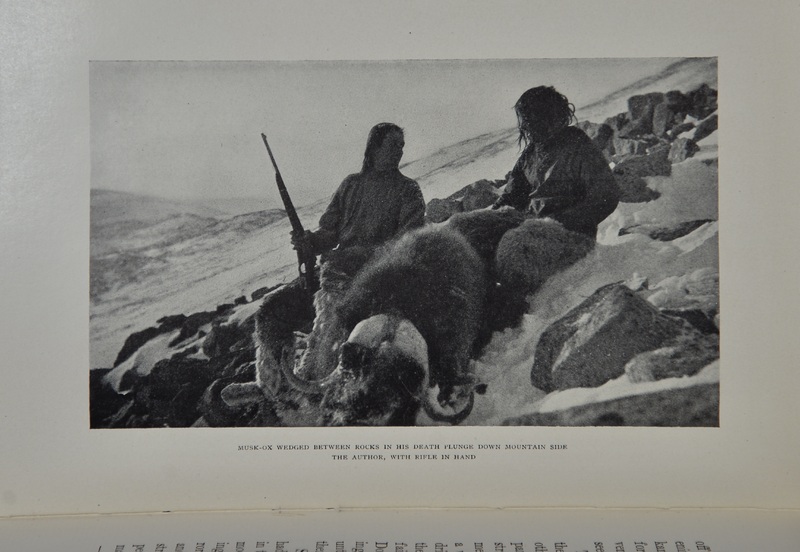

Hunting with the Eskimos: the Unique Record of a Sportsman’s Year Among the Northernmost Tribe Harry Whitney (1873-1936; pictured above) was an American sportsman, adventurer, and author. He traveled to northern Greenland in 1908, staying the winter with the indigenous Inughuit to hunt polar bears, arctic hare, walrus, whales, and the prized muskox. A year after his second hunting trip to Greenland, he published this book about his experiences. Big-game hunting—the hunting of large animals for trophy, sport, or raw materials (such as meat, horn, bone, or oil)—became tremendously popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as wealthy, urban elites grew accustomed to increased amounts of free-time and disposable income. Unfortunately, unsustainable big-game hunting practices eventually led to considerable reductions in wildlife populations from the Arctic to Africa.

Hunting with the Eskimos: the Unique Record of a Sportsman’s Year Among the Northernmost Tribe Harry Whitney (1873-1936; pictured above) was an American sportsman, adventurer, and author. He traveled to northern Greenland in 1908, staying the winter with the indigenous Inughuit to hunt polar bears, arctic hare, walrus, whales, and the prized muskox. A year after his second hunting trip to Greenland, he published this book about his experiences. Big-game hunting—the hunting of large animals for trophy, sport, or raw materials (such as meat, horn, bone, or oil)—became tremendously popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as wealthy, urban elites grew accustomed to increased amounts of free-time and disposable income. Unfortunately, unsustainable big-game hunting practices eventually led to considerable reductions in wildlife populations from the Arctic to Africa.