CASE 1: UNDERSTANDING EXTINCTION - SPECIES & HUMAN IMPACTS

Long before the publication of Darwin’s now-famous treatise on evolution by natural selection, On the Origin of Species (1859), people sought to understand and classify the natural world and humanity’s place within it using religious worldviews and various human-centric classification schemes. Through the mid-1800s, as explorers, collectors, and natural historians encountered an increasingly large number of different plants, animals, and fossils, they attempted to categorize these organisms according to rigid classification schemes. Instead of understanding species diversity according to genetic or functional data as is commonly practiced today, “experts” compartmentalized the world around them according to an organism’s physical characteristics, its "usefulness" to humans, or its perceived level of “complexity”. By doing so, theologians and natural historians fitted organisms into hierarchies which they believed to be part of a Divine plan as outlined in traditional Judeo-Christian thought. Well into the beginning of the 20th-century, the notion that "primitive" mycorrhizal fungi living beneath a single acre of forest could not only be more diverse than all of the human species, but also more important for our survival than any of our cherished livestock, would not have proven palatable to most, even if scientists had the theoretical framework or scientific instruments to measure and understand species diversity.

Throughout the 19th century, the question of whether whole “species” - or kinds - of plants and animals could die out, or go extinct, was also a topic of much speculation and fierce debate. Early proponents of extinction were openly mocked or purposefully silenced because extinction was seen as contradictory to worldviews of a Divine and permanent order set in place by an all-knowing God. For instance, many natural historians used fossilized shells of extinct organisms, lifted to high elevations by plate tectonics over millions of years, as evidence of past cataclysmic events, but refused to acknowledge that these “relics” were evidence of species that had since gone extinct. As Europeans explored further beyond their borders and encountered countless unfamiliar plants and animals, the possibility that fossilized animals could still be alive in some remote, yet-to-be-explored regions of the world kept this view alive, if only on life support. Over time, however, scientists such as Carl Linnaeus, Charles Darwin, and Ernst Mayr helped elucidate both how species emerge (i.e. natural selection and adaptation to different environments) and die out throughout geological time (i.e. abrupt changes in environmental conditions, competition between different species, etc.).

Just as it took considerable effort, evidence, and ideological shifts to understand what constitutes ‘diversity’ in the natural world and to recognize extinction as a natural process, Western cultures were also slow to recognize, or at least openly acknowledge, the ability of humans to extirpate entire species and harm the environment in the process. Similar to how proponents of evolution had to defend their ideas against traditional religious doctrine, early environmentalists such as George Perkins Marsh and John Muir dared to contradict the dominant narrative of human progress through expansion and extraction espoused by colonialists and industrial optimists. By challenging dominant narratives of colonialism and the Industrial Revolution- that increased production and consumption, as well as subjugation of the natural world would ultimately better humanity – these authors and early activists enabled societies to begin recognizing their wrongs and to critically evaluate their impacts upon the planet.

Following the era of Marsh and Muir, the important role plants and animals play in properly- functioning ecosystems, in addition to the relationship between human impacts and extinction across the globe became increasingly clear. From commercial sales of beaver pelts in Paris leading to population declines across Canada and the U.S., to the liberal spraying of harmful pesticides (i.e. DDT) across North America backyards causing the near extermination of America’s eagles and falcons, cries for conservation escalated from a moral plea to an urgent imperative. This shift is perhaps best exemplified by the birth and subsequent explosion of the term “biodiversity”, coined in 1988 to guide conversations surrounding species conservation. Biodiversity - defined as the variety of life, or number of species or varieties in the world or a particular ecosystem at a given time - quickly became a rallying cry during conversations about rapid species lost in an age of globalization and rapid climate change.

Overall, in the course of little-over a century, a mere blip in the expanse of human existence, our view of the natural world has evolved from a poorly-understood assemblage of plants and animals, provisioned by a higher power to be exploited and subjugated for the benefit of humanity, to a complex interconnected network of species whose survival is both affected by and critical to our own. As biologist, environmentalist, author, and early crusader for biodiversity E. O. Wilson voiced the new wave of environmental consciousness in 1988: “diversity is being irreversibly lost through extinction caused by humans...we are locked in a race. We must hurry to acquire the knowledge on which a wise policy of conservation and development can be based for centuries to come.”

Case 1 Items : Understanding Species & Extinction

-

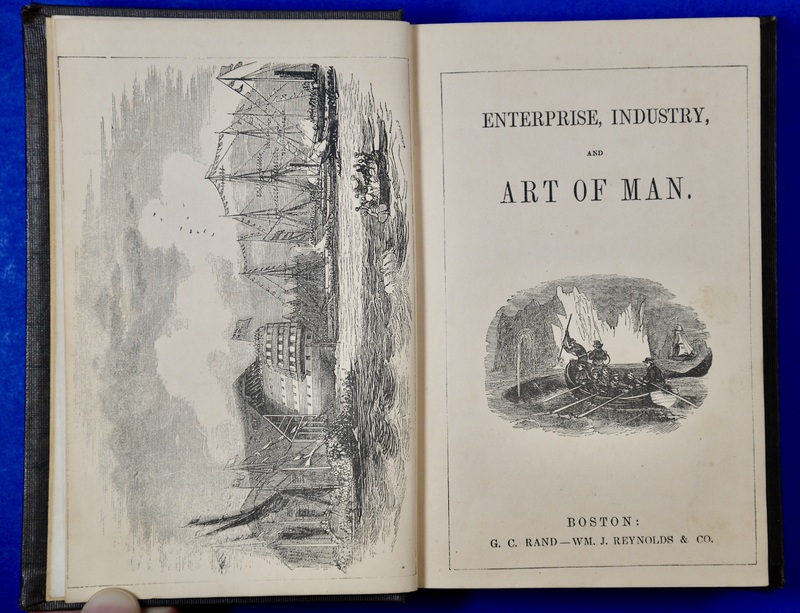

Enterprise, Industry and Art of Man Written as an ode to the power of global trade, Enterprise, Industry and Art of Man is representative of the sense of awe Europeans felt about their ability to “tame” wilderness and harness it to better society during the Industrial Revolution. In the volume’s preface, Goodrich marvels at the origins of the material comforts in his personal study, including a piano whose materials hailed from forests of Brazil, Maine, and elephants in Africa. Meditations on his Argand lamp are of particular interest for “its oil [that] once dwelt in the head of a whale seventy feet in length, and which sloughed the Pacific for half a century.” As this quote (and illustration above suggest), the efficiency and global reach of extractive enterprises such as whaling were examples of progress and sources of pride in the minds of Western cultures.

Enterprise, Industry and Art of Man Written as an ode to the power of global trade, Enterprise, Industry and Art of Man is representative of the sense of awe Europeans felt about their ability to “tame” wilderness and harness it to better society during the Industrial Revolution. In the volume’s preface, Goodrich marvels at the origins of the material comforts in his personal study, including a piano whose materials hailed from forests of Brazil, Maine, and elephants in Africa. Meditations on his Argand lamp are of particular interest for “its oil [that] once dwelt in the head of a whale seventy feet in length, and which sloughed the Pacific for half a century.” As this quote (and illustration above suggest), the efficiency and global reach of extractive enterprises such as whaling were examples of progress and sources of pride in the minds of Western cultures. -

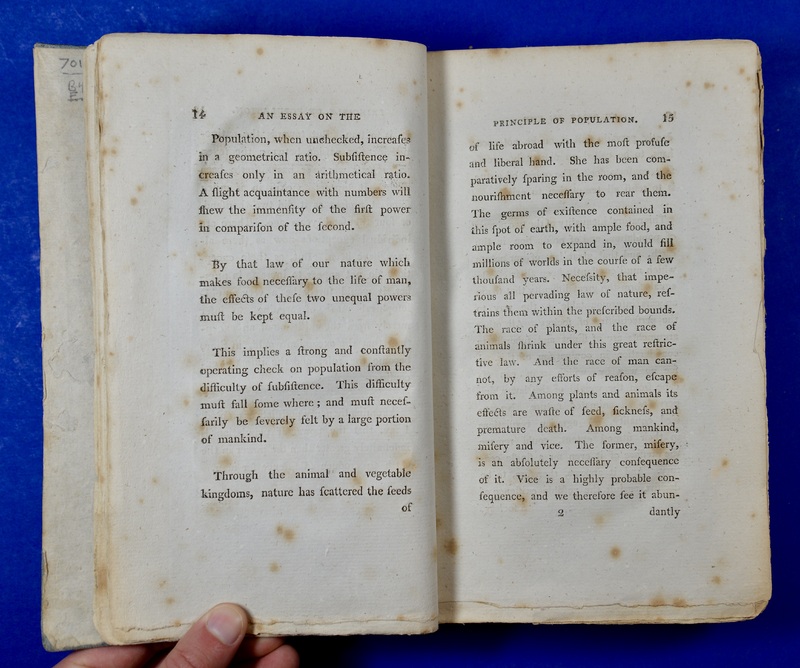

An Essay on the Principle of Population Our first edition of this famous work by Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) was published anonymously so as to avoid backlash. Malthus’ book contrasted with the optimistic views of Enlightenment thinkers such as Jean Jacques Rousseau by warning of future difficulties that would arise as human population growth outpaced food production. This essay sparked discussions about the environmental impacts of exponential human population growth, along with highlighting problems like poverty and famine.

An Essay on the Principle of Population Our first edition of this famous work by Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) was published anonymously so as to avoid backlash. Malthus’ book contrasted with the optimistic views of Enlightenment thinkers such as Jean Jacques Rousseau by warning of future difficulties that would arise as human population growth outpaced food production. This essay sparked discussions about the environmental impacts of exponential human population growth, along with highlighting problems like poverty and famine. -

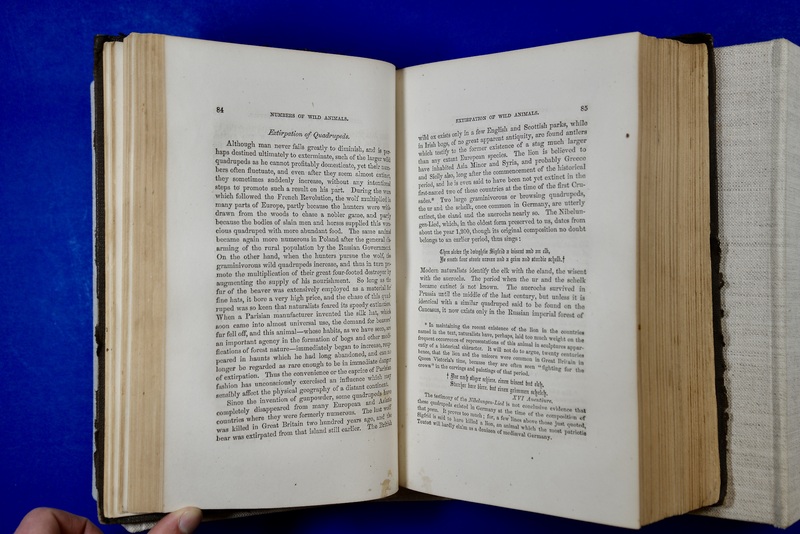

Man and Nature George P. Marsh (1801-1882), Dartmouth Class of 1820, is considered America’s first environmentalist and among the first American natural historians to comment on species extinction. Man and Nature raised concerns about the destructive global impacts of human activities on the environment, including plants and animals. For instance, Marsh describes how European demand for beaver fur nearly doomed the industrious mammal to extinction in the Americas: “Parisian fashion has unconsciously exercised an influence which may sensibly affect the physical geography of a distant continent.” Man and Nature was received favorably and helped sparked the Arbor Day movement, the establishment of forest reserves and the national forest service.

Man and Nature George P. Marsh (1801-1882), Dartmouth Class of 1820, is considered America’s first environmentalist and among the first American natural historians to comment on species extinction. Man and Nature raised concerns about the destructive global impacts of human activities on the environment, including plants and animals. For instance, Marsh describes how European demand for beaver fur nearly doomed the industrious mammal to extinction in the Americas: “Parisian fashion has unconsciously exercised an influence which may sensibly affect the physical geography of a distant continent.” Man and Nature was received favorably and helped sparked the Arbor Day movement, the establishment of forest reserves and the national forest service. -

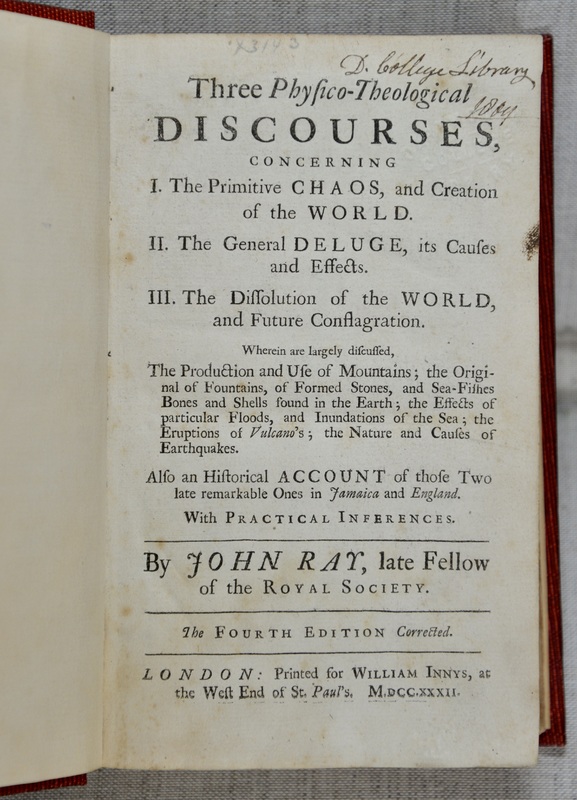

Three Physico-Theological Discourses, Concerning I. The Primitive Chaos, and Creation of the World. II. The General Deluge, Its Causes and Effects. III. The Dissolution of the World and Future Conflagration In this book, English naturalist John Ray elaborates on beliefs about the Great Flood from the Bible's Book of Genesis, during which God decides to reverse and redo creation by returning Earth to a state of watery chaos. While many 18th century natural historians and theologians used discovery of fossils (such as seashells in the Alps) as evidence of a global-scale flood, they did not see them as evidence of extinction. For many people during this time period, the idea of extinction was religiously troubling; it would suggest some flaw with God's divine plan at the beginning of the world. Additionally, belief that all life on Earth forms a Great Chain of Being—from ocean slime to angels—would make extinctions problematic breaks in its links.

Three Physico-Theological Discourses, Concerning I. The Primitive Chaos, and Creation of the World. II. The General Deluge, Its Causes and Effects. III. The Dissolution of the World and Future Conflagration In this book, English naturalist John Ray elaborates on beliefs about the Great Flood from the Bible's Book of Genesis, during which God decides to reverse and redo creation by returning Earth to a state of watery chaos. While many 18th century natural historians and theologians used discovery of fossils (such as seashells in the Alps) as evidence of a global-scale flood, they did not see them as evidence of extinction. For many people during this time period, the idea of extinction was religiously troubling; it would suggest some flaw with God's divine plan at the beginning of the world. Additionally, belief that all life on Earth forms a Great Chain of Being—from ocean slime to angels—would make extinctions problematic breaks in its links. -

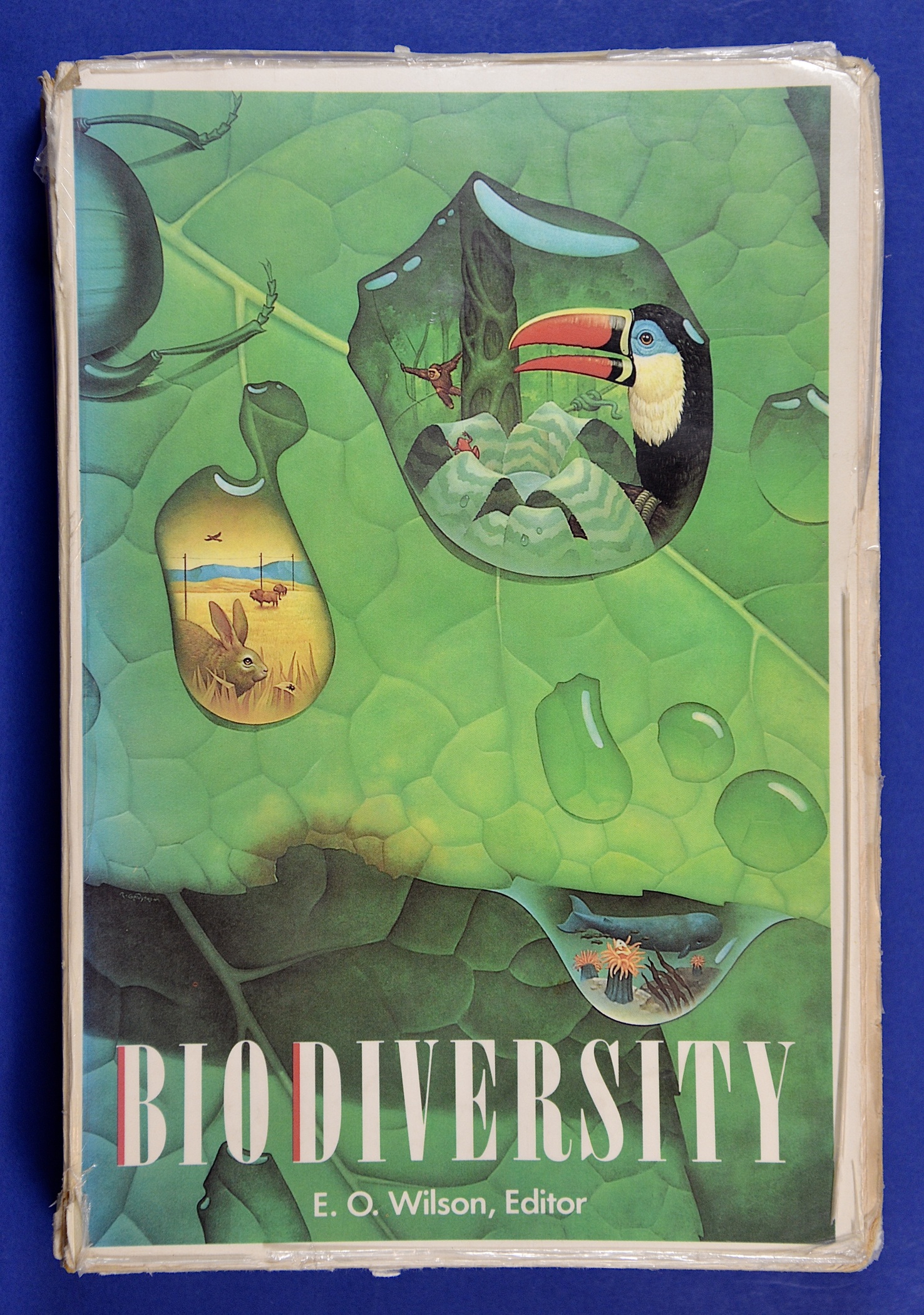

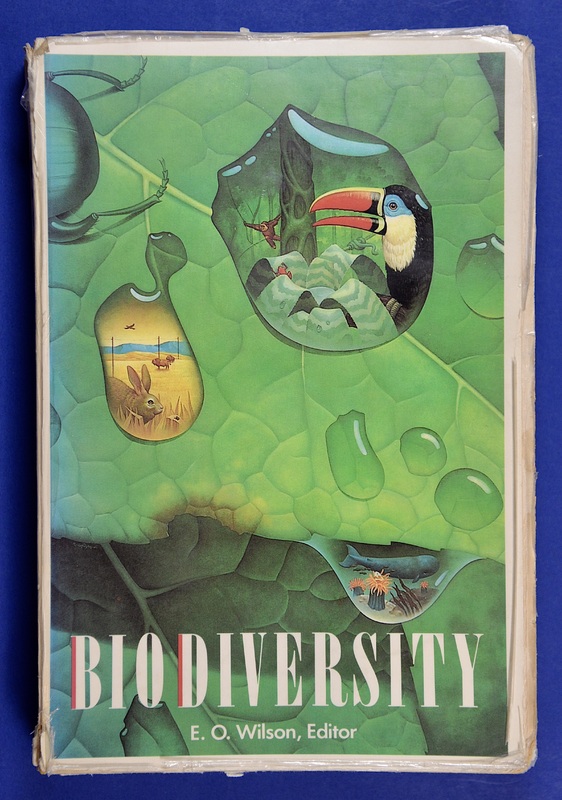

Biodiversity The 1980s witnessed a rise in concerns related to species conservation, due to growing awareness of the close link between economic development, deforestation, and extinction. This shift is evidenced by this publication by famed biologist, naturalist, and writer Edward O. Wilson which features the first appearance of the word “biodiversity” (defined as the variety of life in the world). Wilson writes, “The diversity of life forms, so numerous that we have yet to identify most of them, is the greatest wonder of this planet... The book before you offers an overall view of this biological diversity and carries the urgent warning that we are rapidly altering and destroying the environments that have fostered the diversity of life forms for more than a billion years.”

Biodiversity The 1980s witnessed a rise in concerns related to species conservation, due to growing awareness of the close link between economic development, deforestation, and extinction. This shift is evidenced by this publication by famed biologist, naturalist, and writer Edward O. Wilson which features the first appearance of the word “biodiversity” (defined as the variety of life in the world). Wilson writes, “The diversity of life forms, so numerous that we have yet to identify most of them, is the greatest wonder of this planet... The book before you offers an overall view of this biological diversity and carries the urgent warning that we are rapidly altering and destroying the environments that have fostered the diversity of life forms for more than a billion years.” -

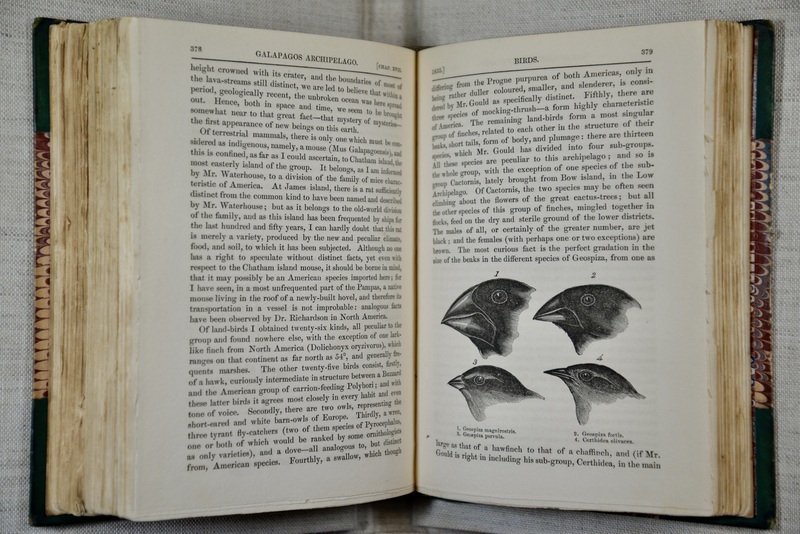

Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle Round the World Charles Darwin’s (1809-1882) narrative of his voyage around the globe features the famous Galapagos finches whose beaks helped him develop his theory of evolution by natural selection. By observing the incredible variety of beak shapes among finch species, he postulated that the beak of an ancestral finch who had arrived at the remote island chain had adapted over time to equip the finches to acquire different food sources. Drawing on the diversity of Galapagos finches and other animals he encountered as examples of evolution by natural selection, Darwin’s theory fundamentally changed human understanding of species and how ecosystems change over time. Darwin posited that many species have died out as a result of competition between animals, and that this process had occurred gradually and continuously throughout the history of life. However, he neglected to clarify the role humans can play in driving species extinction, and believed that sudden disappearances of many species, or mass extinctions, did not actually occur.

Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle Round the World Charles Darwin’s (1809-1882) narrative of his voyage around the globe features the famous Galapagos finches whose beaks helped him develop his theory of evolution by natural selection. By observing the incredible variety of beak shapes among finch species, he postulated that the beak of an ancestral finch who had arrived at the remote island chain had adapted over time to equip the finches to acquire different food sources. Drawing on the diversity of Galapagos finches and other animals he encountered as examples of evolution by natural selection, Darwin’s theory fundamentally changed human understanding of species and how ecosystems change over time. Darwin posited that many species have died out as a result of competition between animals, and that this process had occurred gradually and continuously throughout the history of life. However, he neglected to clarify the role humans can play in driving species extinction, and believed that sudden disappearances of many species, or mass extinctions, did not actually occur. -

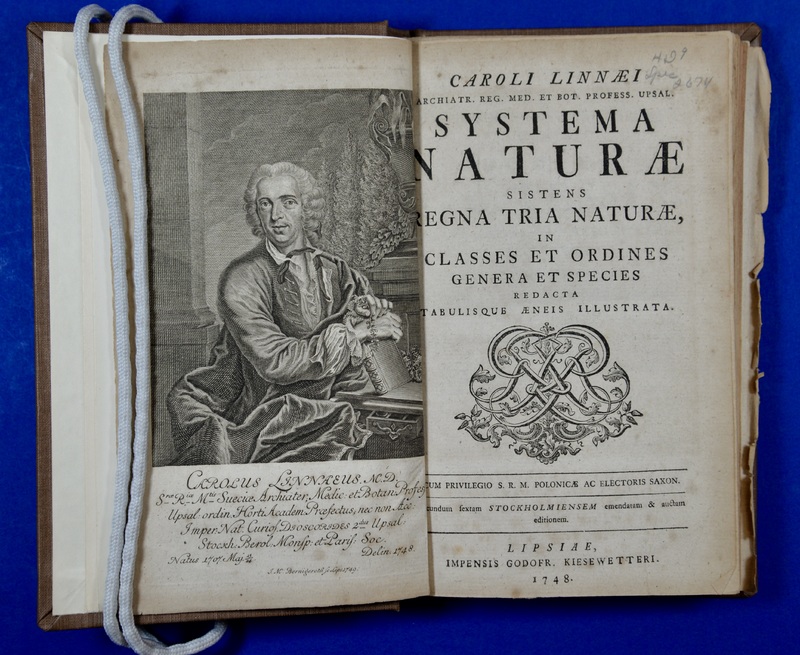

Systema naturæ Swedish naturalist and explorer Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) revolutionized scientific understanding of the diversity of the natural world with the publication of Systema naturæ in 1735. Linneaus established binomial nomenclature, the system of formally classifying and naming organisms according to their genus and species. In contrast to earlier naming conventions that used long descriptive phrases, binomial names do not judge different species on their perceived quality or desirability. Serving as a means by which species could be universally addressed, this new hierarchical system allowed scientists to better conceptualize relationships between organisms.

Systema naturæ Swedish naturalist and explorer Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) revolutionized scientific understanding of the diversity of the natural world with the publication of Systema naturæ in 1735. Linneaus established binomial nomenclature, the system of formally classifying and naming organisms according to their genus and species. In contrast to earlier naming conventions that used long descriptive phrases, binomial names do not judge different species on their perceived quality or desirability. Serving as a means by which species could be universally addressed, this new hierarchical system allowed scientists to better conceptualize relationships between organisms. -

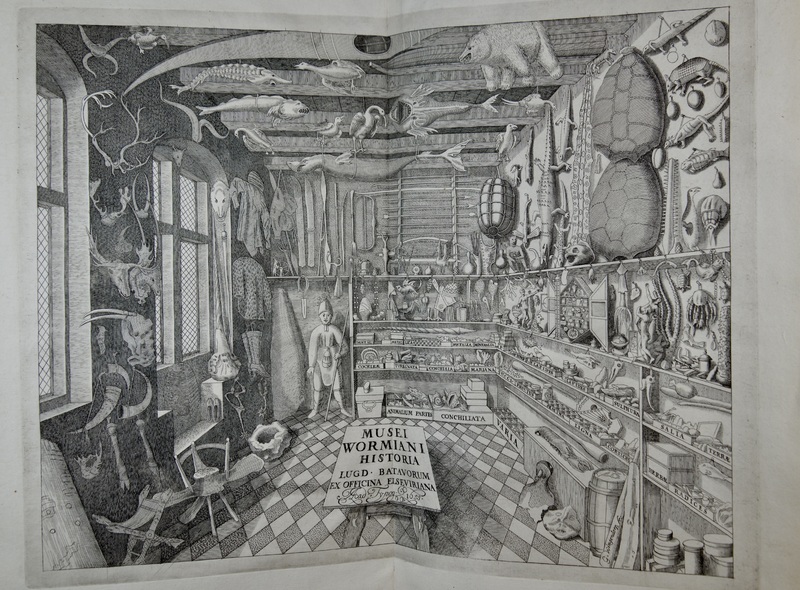

Museum Wormianum Natural historians like Ole Worm (1588 – 1654) sought to classify and understand the diversity of living organisms according to differences in their appearance in order to better understand God’s design in nature. This frontispiece depicts Worm's famous cabinet of curiosities, a massive collection of artifacts from across the globe, which included taxidermized animals, fossils, and weapons and tools owned by indigenous peoples. Look closely and you’ll notice several species now extinct, including the Great Auk, a seabird that Worm also owned as a pet.

Museum Wormianum Natural historians like Ole Worm (1588 – 1654) sought to classify and understand the diversity of living organisms according to differences in their appearance in order to better understand God’s design in nature. This frontispiece depicts Worm's famous cabinet of curiosities, a massive collection of artifacts from across the globe, which included taxidermized animals, fossils, and weapons and tools owned by indigenous peoples. Look closely and you’ll notice several species now extinct, including the Great Auk, a seabird that Worm also owned as a pet.