Dislocation

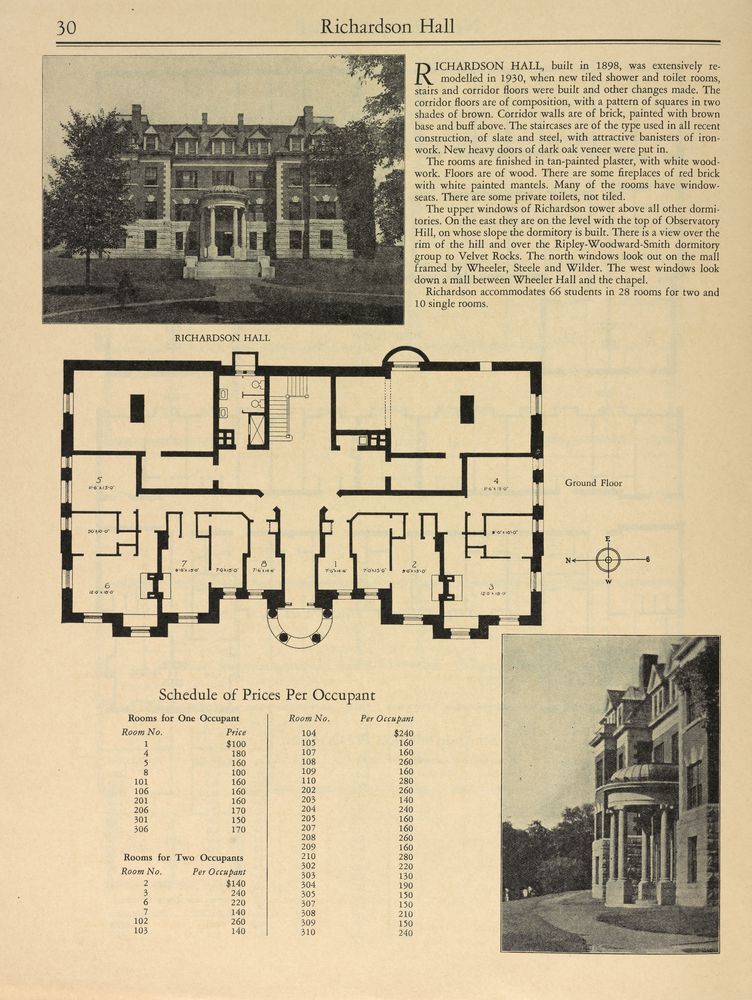

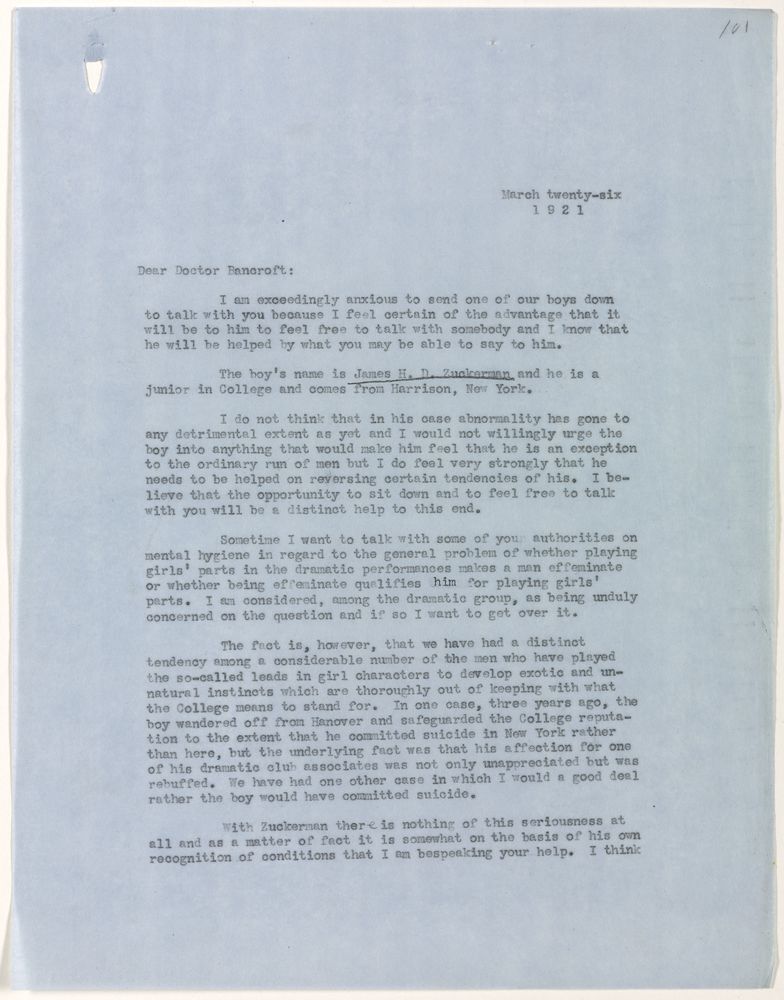

Like any institution of substantial age, Dartmouth bears a speckled past. Part of this past includes the dislocation and exclusion of those less fortunate, or those viewed as “the other” by society. This included students who were Native American, African American, Jewish, Asian, or women, as well as those whose sexual orientation or gender identity put them at odds with society. While Dartmouth was the first Ivy League School to admit African Americans, they were initially not welcome in the College’s dormitories and were often required to board at local homes. When they were allowed on campus, Dartmouth’s cost-based housing system meant that they were relegated to the cheapest rooms, which were generally the least desirable quarters, or in the most remote locations.

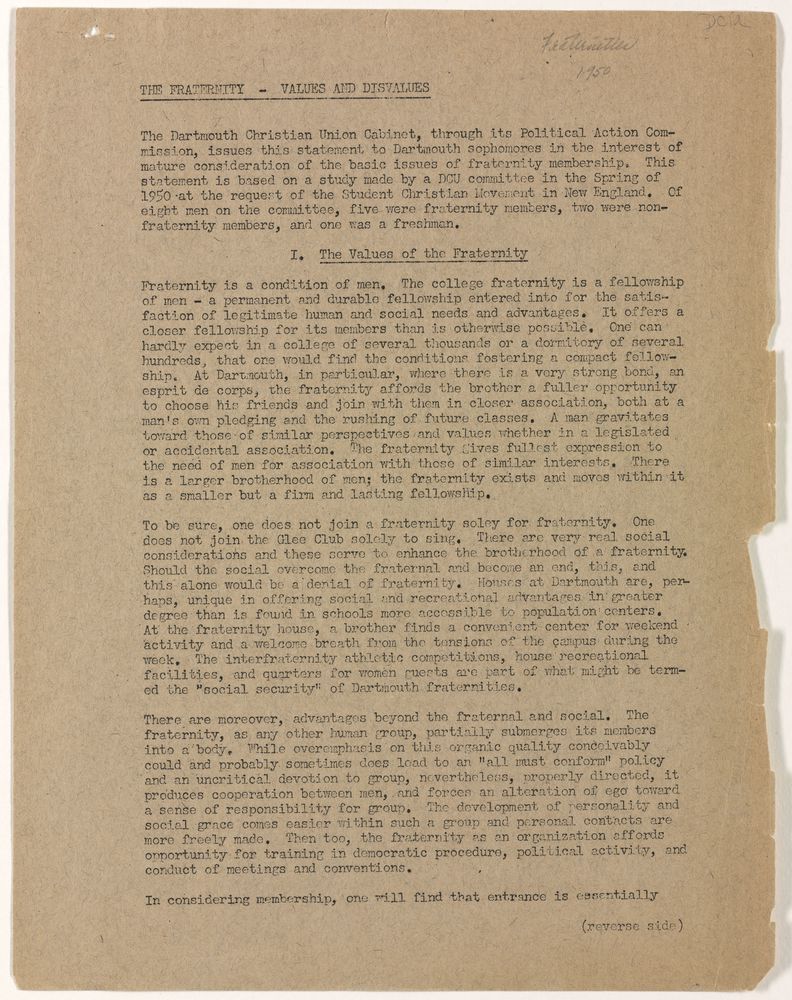

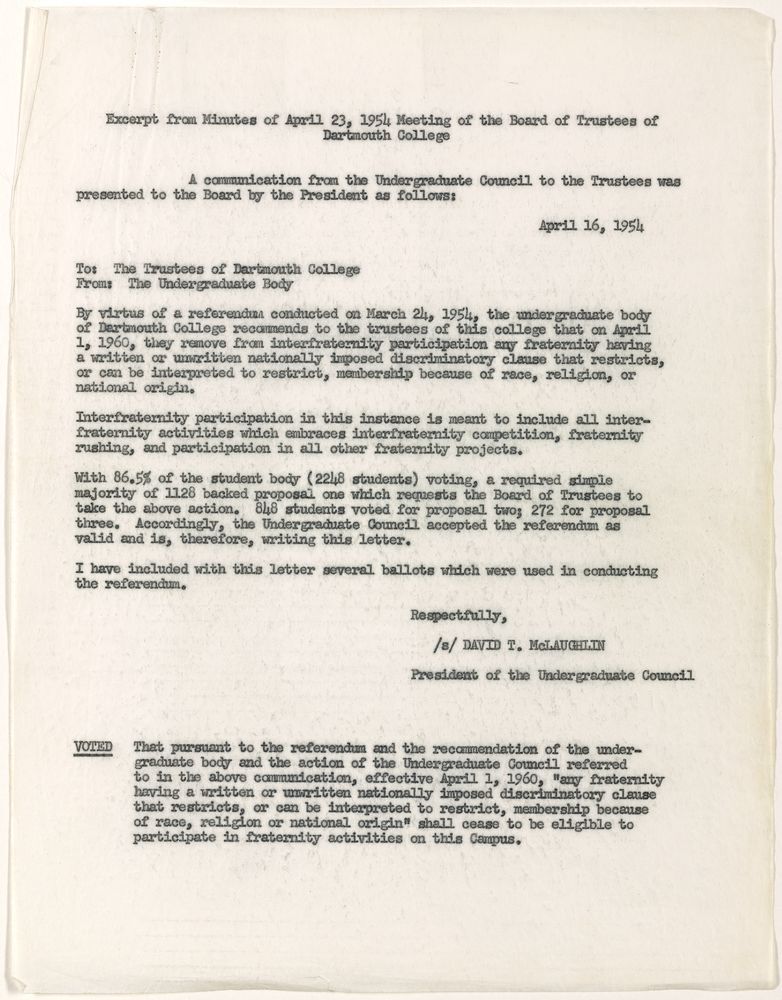

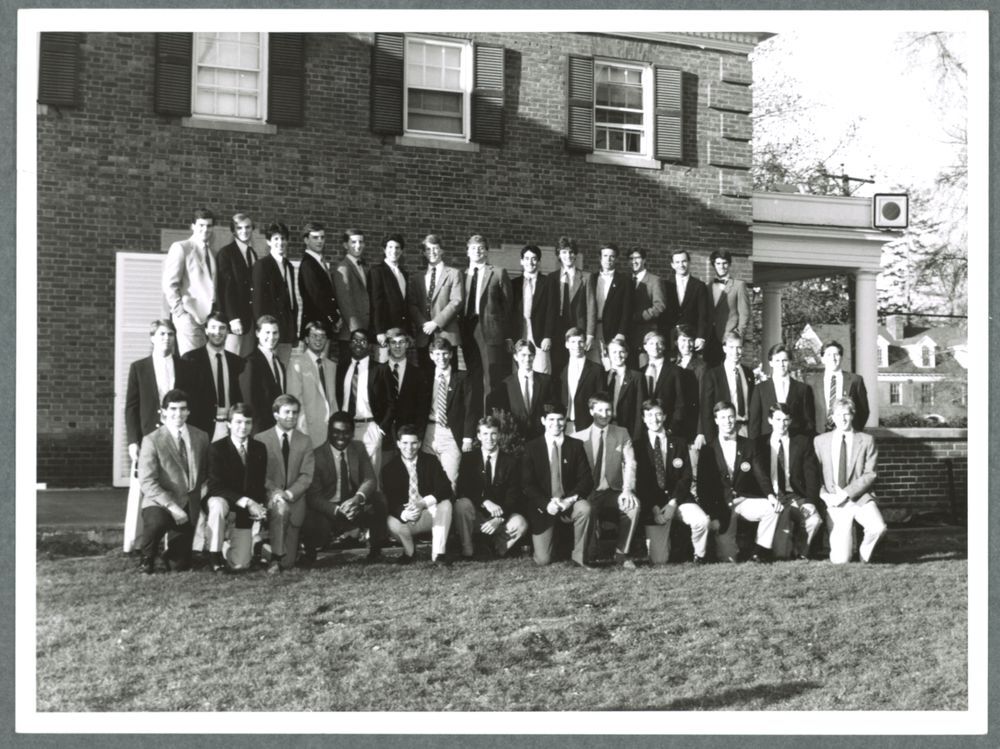

Both Jewish and African-American students faced discrimination in the Greek system until after WWII. In 1949, a group of students, primarily made up of returning veterans, began a campaign to remove discriminatory clauses from fraternity constitutions. By 1964, all of these clauses had either been removed or the fraternities had separated from their nationals. While this was a great victory and a proud moment for Dartmouth it still did not end discrimination at the College.

Previous: Home away from Home: Life in the Dorms -- Next: Going to Dartmouth